The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Does Judge Robert Pitman's Opinion Enjoining Texas's anti-BDS Law Stand Up to Scrutiny?

Short answer: no, not even close

Last Thursday, federal district judge Robert Pitman released a lengthy opinion enjoining on First Amendment grounds a Texas law that requires state contractors to certify that they don't boycott Israel-related products. The opinion is a mess. I'm not going to point out all of the problems it has, but instead will note the two most serious.

First, the opinion misstates the holding of NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware as "recognizing that the First Amendment protects political boycotts." As Eugene V. has explained on this blog, the case actually holds that there is a First Amendment right to advocate economic boycotts, not engage in them. If there were a First Amendment right to boycott for political reasons, then anyone politically opposed to integration, gay rights, and so on would have a First Amendment right to "boycott" minority groups protected by civil rights laws. That's in fact the implication of Judge Pitman's opinion, and it's hard to believe he means it. It's even harder to believe the Supreme Court would endorse his opinion given this implication.

Second, Judge Pitman botches his discussion of a key precedent, Rumsfeld v. FAIR. In that case, the Court held that the law school plaintiffs had no First Amendment right to boycott military recruiters in the face of a federal statute barring recipients of federal funds from discriminating against those recruiters.

Pitman's attempt to distinguish FAIR comes down to the fact that the Court never used the word "boycott" in the opinion:

Claiborne deals with political boycotts; FAIR, in contrast, is not about boycotts at all. The Supreme Court did not treat the FAIR plaintiffs' conduct as a boycott: the word "boycott" appears nowhere in the opinion, the decision to withhold patronage is no implicated, and Claiborne, the key decision recognizing that the First Amendment protects political boycotts, is not discussed.

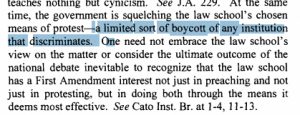

The reason Claiborne is not discussed is FAIR is because, again, Claiborne deals only with the right to advocate a boycott (speech), not to engage in one (economic action) and it's therefore irrelevant. It's true that the word "boycott" does not appear in FAIR, but it's also true that (a) what the law school plaintiffs were doing was clearly within the definition of the word boycott; and (b) the law school plaintiffs, in their Supreme Court brief, themselves described what they were doing as a boycott. Here's the relevant excerpt from the brief.

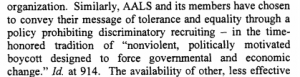

Moreover, the Association of American Law Schools, acting as an amicus and representing the interests of American law school membership, also described the actions of the law schools as a "boycott."

So the notion that FAIR "is not about boycotts at all" is both contrary to the ordinary meaning of the word "boycott" and contrary to the way the case was presented to the Supreme Court by the law schools challenging the federal law at issue

Show Comments (74)