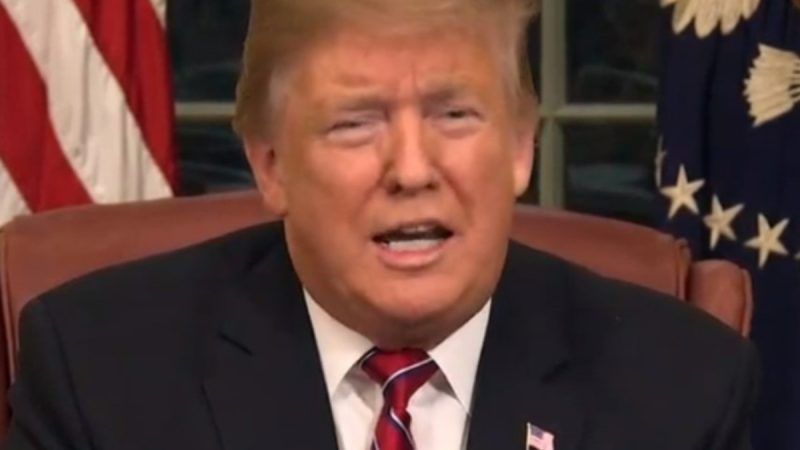

Trump May Not Be Guilty of Obstruction, but He Is Guilty of Arrogant Stupidity

The president heedlessly created the appearance that he was trying hard, though ineptly, to hide something.

In detailing 10 episodes that could be viewed as evidence that Donald Trump obstructed justice as president, Special Counsel Robert Mueller's report suggests several promising lines of defense, stronger in some cases than others, that call into question one or more of the three elements required for a conviction: an obstructive act, a nexus to an official proceeding, and a corrupt intent. A jury might very well conclude that the case has not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

But it's not up to a jury, since the Justice Department, per its longstanding policy, was never going to prosecute a sitting president. It's up to Congress, which in deciding whether a president has committed "high crimes and misdemeanors" is unconstrained by statute or by the standard of proof that applies in a criminal trial. Democrats will be inclined to conclude that the amorphous standard for impeachment has been satisfied, while Republicans will say that Mueller's decision not to reach a firm conclusion about the criminality of the president's conduct amounts to an exoneration.

To any fair-minded reader who is not blinded by partisan bias, however, one thing is clear: Donald Trump, if he is guilty of obstructing justice, is really bad at it. Over and over again, he opened his mouth when he should have kept it shut, lied clumsily and transparently, ignored warnings from multiple advisers that his public and private actions could be construed as obstruction, and did everything he could to reinforce the impression that he was a man with something to hide.

Attorney General William Barr, who unlike Mueller has announced that there is no provable obstruction case against Trump, today emphasized that "the President took no act that in fact deprived the Special Counsel of the documents and witnesses necessary to complete his investigation." But as the Mueller report points out, you can be guilty of obstruction even if your efforts are unsuccessful, and Trump's failure was due largely to his subordinates' resistance.

You can also be guilty of obstruction even if you did not commit an underlying crime that you are trying to cover up. That is how Trump came to be credibly accused of obstructing an investigation of a crime (conspiring with Russia to influence the presidential election) that never happened, then obstructing the investigation of his obstruction. And in the end, he has no one to blame but himself.

Trump alternately cajoled and condemned potential witnesses against him (his former national security adviser, Michael Flynn; his former personal lawyer, Michael Cohen; and his former campaign chairman, Paul Manafort) and subordinates he thought should be doing more to protect him from the Russia investigation (FBI Director James Comey, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, White House Counsel Donald McGahn). He did this publicly as well as privately.

"Many of the President's acts directed at witnesses, including discouragement of

cooperation with the government and suggestions of possible future pardons, occurred in public view," Mueller notes. "While it may be more difficult to establish that public-facing acts were motivated by a corrupt intent, the President's power to influence actions, persons, and events is enhanced by his unique ability to attract attention through use of mass communications. And no principle of law excludes public acts from the scope of obstruction statutes. If the likely effect of the acts is to intimidate witnesses or alter their testimony, the justice system's integrity is equally threatened."

Trump publicly denied making requests or issuing instructions aimed at containing or stopping the Russia investigation, such as asking Comey to leave Flynn alone or telling McGahn to fire Mueller. In almost every such case, the report concludes that "substantial evidence" favors the subordinate's account.

Trump fired Comey for refusing to publicly clear his name, even while acknowledging that the decision would look bad and probably would prolong the investigation he was trying to contain. (Mueller was appointed a week later.) He offered a completely implausible cover story for Comey's dismissal that he admitted was not true a couple of days later.

Trump deliberately misled the public about his efforts to build a Trump Tower in Moscow, a deal that was still being pursued as late as July 2016. He deliberately misled the public about the nature of a meeting between his son and a Russian lawyer who had promised dirt on Hillary Clinton. He whined endlessly, publicly and privately, about the unfairness of the "witch hunt" that Mueller was conducting and Sessions' failure to protect him from it. He ignored his lawyers' entreaties to stop commenting on the investigation because it was hurting his case.

Although it turned out that Trump was telling the truth when he denied illegal "collusion" with the Russians, that does not mean his attempts to undermine the investigation could not qualify as obstruction. "Obstruction of justice can be motivated by a desire to protect non-criminal personal interests, to protect against investigations where underlying criminal liability falls into a gray area, or to avoid personal embarrassment," Mueller notes. "The injury to the integrity of the justice system is the same regardless of whether a person committed an underlying wrong. In this investigation, the evidence does not establish that the President was involved in an underlying crime related to Russian election interference. But the evidence does point to a range of other possible personal motives animating the President's conduct. These include concerns that continued investigation would call into question the legitimacy of his election and potential uncertainty about whether certain events—such as advance notice of WikiLeaks's release of hacked information or the June 9, 2016 meeting between senior campaign officials and Russians—could be seen as criminal activity by the President, his campaign, or his family."

On the question of whether a president's obstruction of justice can include the exercise of his Article II powers, such as the hiring and firing of executive branch officials, Mueller firmly disagrees with Barr, saying a corrupt motive can make such acts criminal. Barr, by contrast, argues that Trump legally could have fired Mueller or ordered an end to the investigation, regardless of his motive, because the Constitution gives him that authority. But Barr says he did not evaluate the obstruction case against Trump based on that premise, and much of Trump's suspicious conduct—including his public lies and his apparent efforts to influence what Flynn, Cohen, and Manafort told investigators—does not fall into this category.

The obstruction case against Trump is not conclusive. In fact, his indiscretion and ineptness could be seen as evidence that he did not think he was breaking the law. But at the same time, he recklessly created the appearance that he was guilty of something, disregarding sound legal advice from people who knew better. If arrogant stupidity were a crime, Trump would be guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Show Comments (168)