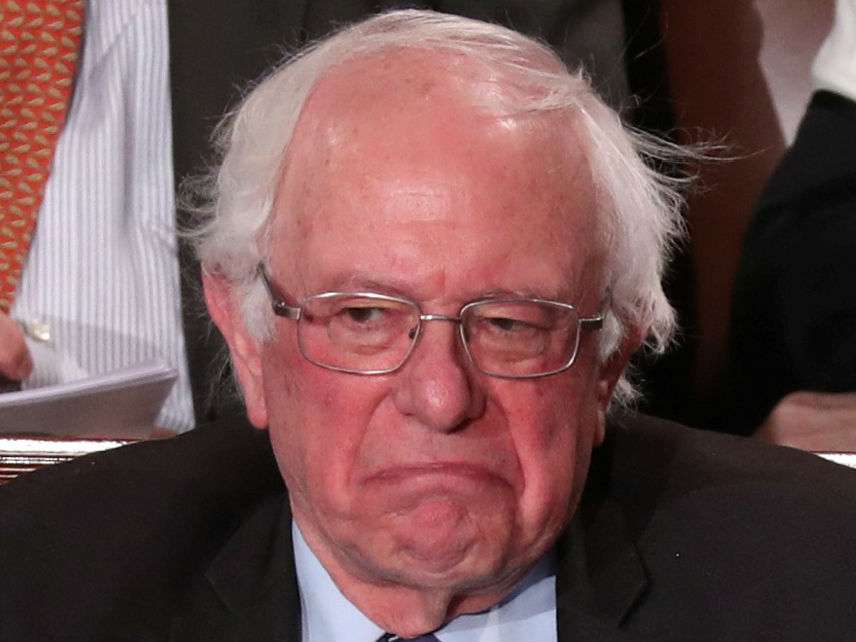

Bernie Already Won. So Why Run Again?

The Vermont independent has yanked Democrats so far to the left that his competitors are becoming mini-mes.

Is there another outsider who yanked an unwilling political party further in his or her ideological direction in a shorter period of time than Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)? I mean, other than Donald Trump.

Back when he was polling in single digits at the outset of the 2016 presidential primary, Sanders and his position of being against every single international trade agreement since World War II on the inaccurate grounds that they facilitate a "race to the bottom" were still considered outliers within the Democratic Party. By October 2015 his unlikely polling surge helped persuade consensus front-runner Hillary Clinton to downgrade her opinion on the Trans-Pacific Partnership from "gold standard" to junk.

Where are the Democrats now? "It's a pretty safe bet that no candidate is going to campaign as a free trader in the 2020 Democratic primary, setting up the potential for a large-scale realignment on a major policy issue for the party," Vox concluded this week.

Advantage Bernie, if not necessarily the country.

What about Sanders' radical campaign agenda item of providing free college tuition? Two years later, Inside Higher Ed reported, "Free college goes mainstream." His $15 federal minimum wage — originally opposed then later adopted by Clinton, despite being warned against doing so by the same liberal economist whose research is most often cited by proponents — was introduced in a House bill just last month.

Back when the 2016 primary was at its testiest, Clinton's favorite critique of the senator's proposals, particularly his "Medicare for all" plan, was that "the numbers just don't add up." This year? Good luck finding a Democratic candidate who doesn't back Medicare for all, at least as a feel-good slogan.

Maybe it took the election of an honest-to-God fabulist as president, but Democrats not named Amy Klobuchar seem to be divorcing themselves from any sense of real-world constraints on their apparently boundless aspirations. "Now it is time to complete that revolution," Sanders told his supporters Tuesday as he announced another shot at the presidency. The word choice wasn't accidental.

In addition to single-payer healthcare, free tuition and the $15 minimum wage, Sanders "will also tout proposals to mandate breaking up the biggest Wall Street banks; lower drug prices through aggressive government intervention; new labor laws to encourage union formation; curbed corporate spending on elections; paid family and medical leave; gender pay equity; and expanded Social Security benefits," the Washington Post reported. And don't forget the Green New Deal!

The real story here is not that Sanders is cranking his Spotify playlist of progressive greatest hits (including stuff I actually like, such as legalizing marijuana, reducing cash bail and adopting a more restrained foreign policy). It's that the rest of the 2020 Democratic field is already with him on most of the economic and budgetary issues that drive his fans wild with happiness and me to drink.

Which suggests the question: Why run, at age 77, when you've already won?

Maybe Sanders wants to prove to himself that the revolution he helped start is real enough to be enacted into society-altering legislative change. Here, despite the persuasive successes listed above, I suspect Bernie and his supporters may again end up tasting bitter disappointment.

Despite the breakout success of such oxygen-gobbling, Sanders-influenced stars as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), it is moderate Democrats, not progressives, who have repainted the House of Representatives blue. The national political media may love telegenic coastal lefties, but the policymaking future of the party probably lies closer to the unorthodox centrism of purple-state nonconformists such as Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.).

And the track record of big progressive policy ideas colliding with reality is just not great — even in the late stages of a long economic expansion.

Bernie's home state of Vermont passed single-payer healthcare, only to scrap it when the price tag became clearer. Maryland enacted a "millionaires tax" more than a decade ago only to discover that rich people can afford to move. And Californians can testify about the gaps between progressive dreams and on-the-ground costs when it comes to the Sanders/Ocasio-Cortez vision of high-speed rail.

It's possible that these are just growing pains for the revolutionary wing of the Democrats. Maybe there are solid national majorities that will back the kind of economic policies popular in Los Angeles, Seattle and New York. But there's an alternative theory worth considering.

Bernie Sanders, who has been Bernie Sanders almost forever, only became a national phenomenon after emerging as the last real candidate standing against Hillary Clinton, a comparatively inauthentic machine politician who tried valiantly to make her nomination look preordained. Americans don't take kindly to coronations, and many of the Democrats I know who flocked to Sanders did so not because they agreed with him on everything he said, but because he meant it at least.

In a campaign with just two choices, ideology can be overrated, even overlooked. But Democrats are now hurtling toward 2020 with a dozen declared candidates, half of whom agree with Sanders on economics. It's going to take more than a bag full of trillion-dollar promises to make Sanders the "at least I mean it" candidate this time.

This article originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times.

Show Comments (91)