Trump Blames Hurricanes for Growing Budget Deficit. Entitlements Are the Real Problem.

Trump blaming the budget deficit on hurricanes is much the same as those on the left who are trying to pin the blame on last year's corporate tax cuts.

In response to questions about America's growing budget deficit, President Donald Trump on Wednesday said natural disasters were partially to blame.

After first identifying (somewhat correctly) increased levels of spending on the military and domestic programs—"I had no choice but to do it," Trump said of those spending hikes—as culprits of the widening budget deficit, Trump quickly pivoted to suggest that the deficit was being driven by acts of God.

"We also have tremendous numbers with regard to hurricanes and fires and the tremendous forest fires all over," Trump said. "We had very big numbers, unexpectedly big numbers."

Trump and his fellow Republicans are facing some heat this week after the Treasury Department announced on Monday that the budget deficit had grown by 17 percent during fiscal year 2018—which ended on September 30. At $790 billion, the deficit for fiscal year 2018 was the highest since 2012.

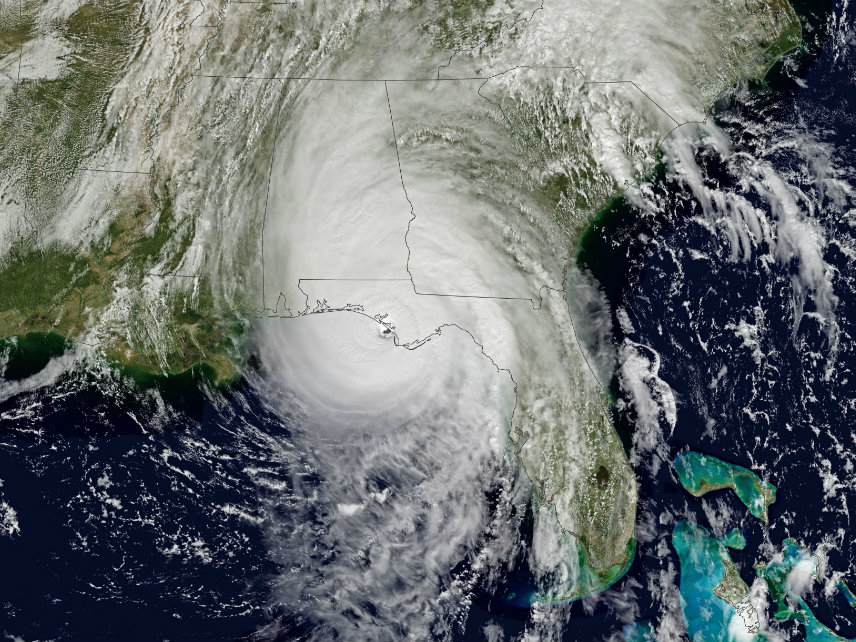

It's true that natural disasters can put big dents in the federal budget. Last year, Congress spent $140 billion in emergency funding to cover the costs of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria after they devastated parts of Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico. Congress is currently considering an emergency funding bill to cover the damage caused by Hurricane Michael, which slammed into the Florida Panhandle last week. It is unclear what the final cost of that bill may be.

Making matters worse is the fact that Congress has never been particularly serious about prioritizing emergency disaster funding by offsetting those costs with other spending cuts. Even in the halcyon days when Republicans cared enough about limiting federal spending to pass the Budget Control Act of 2011, there was a special loophole allowing emergency disaster spending that did not count against the budget cap.

So, yes, Congress often adds to the deficit when it passes emergency spending bills in the wake of natural disasters. But all that is somewhat beside the point, because it's not tropical storms that have put America on a trajectory to have a $1 trillion deficit by the end of next year. The deficit is being driven by entitlements. Social Security and Medicare are on pace to run a $100 trillion deficit over the next 30 years, according to Congressional Budget Office projections, while the rest of the government is projected to operate with a surplus.

This is an important distinction. If the rising deficit in 2018 were able to be blamed on rare events like a series of particularly bad storms or forest fires, then it would call for a different course of action than if the deficit is being driven by baked-in costs connected to entitlement programs that will only get more expensive as some 74 million Baby Boomers head into retirement. As Brian Riedl, a senior fellow with the Manhattan Institute and longtime congressional budget aide pointed out in an interview with Reason published earlier today, the $1 trillion deficit America faced after the Great Recession was an entirely different matter than the nearly $1 trillion deficit facing the country today:

The last time we had a trillion-dollar deficit, it was entirely the result of the Great Recession, and when the recession ended and we had some small policy changes, the deficit somewhat fixed itself. The danger is that the fixing of that trillion-dollar deficit from 2009 has created a false sense of security. People say 'well, we had a trillion-dollar deficit in 2009 and the sky didn't fall.'

The difference is: that trillion-dollar deficit was a temporary result of the recession and fixed itself when the recession ended, but this trillion-dollar deficit is caused by 74 million retiring Baby Boomers. It's not going to fix itself. So while deficit hawks might sound like the Boy Who Cried Wolf after 2009, it's a totally different situation now.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) seems to understand this, even if Trump does not. In an interview with Bloomberg, McConnell said the current deficit level was "disappointing" and the result of bipartisan unwillingness to address entitlement spending.

That's also why it's probably right to be skeptical about Trump's headline-making request on Wednesday that all cabinet secretaries come up with a plan to cut 5 percent from their budgets.

Plans to slash spending are always welcome, of course, but Trump called for similar cuts in his budget plan for this year, only to have Congress ignore those plans and hike spending anyway. Spending hikes that Trump signed into law—and, in the case of the additional $82 billion in funding for the military, spending increases that he bragged about accomplishing. Seemingly every Trump rally also includes presidential promises to protect Social Security and Medicare from changes.

Trump blaming the budget deficit on hurricanes is much the same as those on the left who are trying to pin the blame on last year's corporate tax cuts. Both are correct, to a point, in that emergency spending and tax cuts without offsetting spending reductions will widen the gap between how much money the government takes in and how much it spends. Both explanations ignore the real problem—one that is far more expensive and politically difficult to solve.

Show Comments (47)