North Carolina's Redistricting Mess Shows Why State Legislatures Must Limit Partisan Mapmaking

The status quo is bad for voters, candidates, and democracy. State legislatures should try to fix it.

A three-judge panel of judges has ruled, for the second time this year, that North Carolina's congressional districts are unfairly gerrymandered to give Republicans an electoral edge and must be redrawn before November. The decision has thrown crucial congressional races into chaos.

That doesn't mean the decision is wrong. If congressional districts are unlawful, they should not be used for any election, no matter how disruptive it might be to remedy them. The problem is that the line between unfair and unlawful redistricting is pretty blurry.

Start with what's most obvious: North Carolina's districts were slanted to favor Republicans. This is beyond doubt. Prior to a GOP-controlled redistricting process in 2011—GOP-controlled because state lawmakers handle congressional district-drawing and the GOP won tons of state legislative seats in 2010—Democrats held eight of the state's 13 seats in Congress. In the first election held on the new map, Republicans won a 9–4 majority in the state's congressional delegation, even though Democrats received more aggregate votes.

Such is the power of redistricting. By packing parts of the state with high concentrations of Democratic voters into a few incredibly odd-shaped districts, Republican mapmakers gave their candidates an edge in other parts of the state.

Take the former 12th district. It was a serpentine monstrosity more than 200 miles long but never more than about 20 miles wide, winding from deep blue Charlotte to deep blue Winston-Salem and avoiding most of the Republican strongholds in between. In redistricting talk, these kinds of districts are known as "vote sinks."

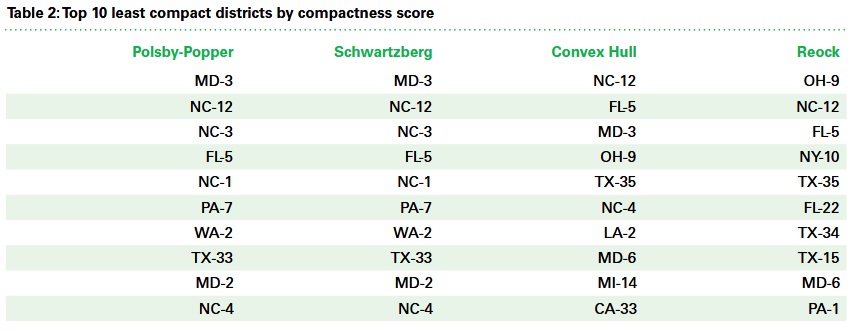

The 12th district has been featured in practically every article, analysis, and report on redistricting since 2011. One statistical analysis of the compactness of congressional districts rated it either the first or second most gerrymandered district in the country, depending on which measurement is used. The same report, from the Philadelphia-based geospacial mapping firm Azavea, ranked North Carolina as the nation's second most gerrymandered state—trailing only Maryland, a state that itself looks like a gerrymandered district.

Everyone agrees North Carolina was gerrymandered in 2011, but that in itself is not necessarily illegal. Redistricting is a fundamentally political process, and state lawmakers and courts have been unwilling to put objective limits on how much partisan influence is OK.

But there are legal limits when gerrymandering affects racial minorities, and it was on those grounds that federal judge Roger Gregory ruled in 2016 that North Carolina's 1st and infamous 12th districts must be redrawn. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed. Redrawing those two districts required shifting others around, but the resulting map drew another legal challenge for unfairly boosting Republican candidates.

In January, a panel of three federal judges ruled that the entire map would have to be redrawn before the 2018 election. As it did with other gerrymandering cases out of Wisconsin and Maryland this year, the Supreme Court declined in June to rule decisively on North Carolina's map. Instead it sent the matter back to the lower court and asked for more evidence that voters from all across the state—rather than from merely a few districts—were disenfranchised.

That brings us to Monday. After hearing arguments from voters in all 13 of North Carolina's congressional districts, the same three-judge panel from January ruled 2–1 that the state's map is still unconstitutional and must be redrawn. The U.S. Constitution, Judge Jim Wynn wrote for the majority, "does not allow elected officials to enact laws that distort the marketplace of political ideas so as to intentionally favor certain political beliefs, parties, or candidates and disfavor others."

By ordering the state legislature to come up with a new district map by mid-September, the judges have created their own distortions. Candidates standing for election in just 70 days now have no idea in which districts they reside, and neither do voters. The primary elections have already happened, but may need to be redone in new districts before November. Meanwhile, the specter of partisanship hangs over the ruling—as conservative media quickly pointed out, the two judges who voted to toss the North Carolina congressional map were appointed by Democrats; the dissenting vote came from a Republican appointee.

There should be little sympathy for Republicans who claim that partisanship overturned their own obviously partisan efforts to influence the outcome of elections. Still, the possibility that judicial oversight of redistricting could become another level in an endlessly partisan game is also worrying. Should the fairness of congressional districts really depend on which set of judges is looking at them? That's no solution.

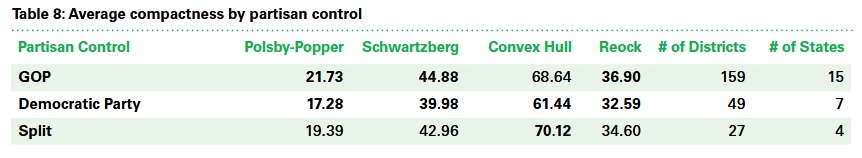

And while Republican-drawn gerrymanders in North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania have drawn the most attention in the media and courts, Democrat-drawn maps made in 2011 were actually less compact on average. Clearly, neither major party has the moral high ground here.

As in Pennsylvania earlier this year, North Carolina's ongoing redistricting crisis demands that both major parties agree to objective, measurable limits on partisan gerrymandering. Statistical measurements like those that identified the old North Carolina 12th as the nation's most gerrymandered district can be part of this solution, as can overlayed data about electoral outcomes—like the "Efficiency Gap" measure that was at the center of this year's Wisconsin redistricting case that reached the Supreme Court.

Each of those measurements has its limits, and any standards set would be arbitrary by nature. Do you prohibit districts with a Polsby-Popper score of less than 20 or less than 15? Those are questions that state legislatures should settle, not courts; and the same standards don't have to apply everywhere. But without some limitations, partisan fights over redistricting will only get worse. Remember, we're only three years away from the next scheduled redrawing of all congressional districts following the 2020 census.

The current redistricting process leaves voters confused at best, disenfranchised at worst. It invites partisanship into the legal system. And it produces congressional majorities that do not always reflect the will of the people. Lawmakers have the tools to write some rules for this ugly political game, and they should seize the opportunity.