Police Raided Their Home and Business, Seized Their Money, and Nearly Ruined Their Lives Over Some Weed

After two years of fighting in court, a California couple is getting back $53,000 that was seized from them through asset forfeiture.

When police officers raided the home and business of Paul and Maricel Fullerton and held the Woodland, California, couple at gunpoint in February 2016, they brought back a big haul.

A local multi-agency narcotics task force seized $55,000 from the Fullertons, along with 22 pounds of processed marijuana and several firearms. It had all the appearances of a major drug bust, except for the targets: a retired fire captain and a hospice nurse.

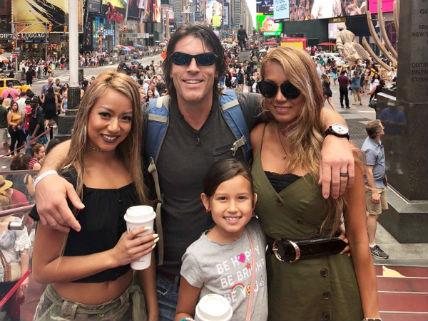

Now, after two years of protracted court proceedings that nearly ruined the Fullertons' lives and careers, and briefly led to their separation from their child, Yolo County law enforcement will walk away with around $2,000, split between several agencies, and a misdemeanor marijuana conviction and to show for its efforts.

The Yolo County District Attorney finalized a settlement on Monday to return $53,000 that the Yolo Narcotics Enforcement Team (YONET) seized from the Fullertons. The Fullertons mostly prevailed, and all it cost them was around $100,000 in legal fees, fines, and other costs.

The Fullerton's case was only one of more than 3,000 asset forfeiture cases initiated in California in 2016, according to an annual report by the state attorney general, but it's a small example of both how the drug war is prosecuted and how it is changing: In the middle of the Fullerton's case, California voters decided that the sort of offense that led heavily armed YONET agents to raid the Fullertons' home and business should instead be treated as a minor nuisance or business license violation.

"After this long time period, yeah, I'm relieved, but I'm still angry inside most of all, because I know that there's a system that's basically broken," says Fullerton, 46, of Woodland, California. "And if an honest, hardworking, disabled fire captain can get rolled up in these cogs of injustice, to me it isn't really over."

Fullerton was a firefighter for 25 years until an on-the-job spinal cord injury ended his career and left him with 12 screws and three metal plates in his neck. He found relief from prescription pain pills through medical marijuana. In 2012 he opened up his own hydroponics store, Lil' Shop of Growers, in Woodland and joined a local medical marijuana collective.

But his new business didn't sit well with local law enforcement, which began investigating the former fire captain after allegedly receiving a tip that he was selling large amounts of marijuana out of his store.

Local police claim Fullerton gave 1.7 grams of marijuana—about a joint-and-a-half—to an undercover officer and later agreed to sell the informant more marijuana for $300. Video evidence of the transactions in hand, YONET agents raided Fullerton's store and home on Feb. 18, 2016.

Fullerton had worked for decades alongside local police and says he, his wife, and his business had a good reputation in town. In 2008, a "Heroes Award Luncheon" put on by the Yolo County Chapter of the American Red Cross recognized Fullerton and three other UC Davis firefighters for their role in saving a man's life.

But in 2016 he ended up splayed on the ground, looking up the barrel of an assault rifle being leveled at him by a masked police officer.

Yolo County prosecutors hit both Paul and Maricel Fullerton with a host of felony charges including marijuana sales, possession of marijuana for sales, cultivation of marijuana, importation of a large-capacity rifle magazine, and child endangerment.

"Maricel was prosecuted despite having been told by officers that this wasn't about her, because it gave them more leverage over Paul," Ashley Bargenquast, the Fullertons' lawyer in their civil forfeiture case, says. "It was really a fairly ugly prosecution that demonstrates some of the more political and more manipulative patterns of investigations."

Worse, because of the child endangerment charge, the Fullertons' daughter was temporarily placed in protective custody.

"They took my daughter away and she wasn't allowed to come home for 10 days… I've totally lost my faith. It's scary that they can just wrongfully charge people," Maricel Fullerton told The Daily Democrat. "I'm in constant fear of what's going to happen to us—to my daughter."

The Fullertons dispute nearly every part of the law enforcement narrative. Fullerton says the police informant baited him with a sob story about a sick friend. He attempted to just give the marijuana to the informant, who insisted on shoving money into his hand. He also says he put that money in a fireman's boot on the desk, which he uses to collect cash to donate to charity.

The Fullertons also say the gun safe in their house was unlocked—part of the justification for the child endangerment charge—because police opened it.

Prosecutors dropped the gun charges after it was shown they were legally owned, and while the case was dragging on, California voters approved a ballot initiative that legalized recreational marijuana. The ballot measure also transformed the Fullertons' marijuana charges into misdemeanor offenses.

As part of a plea deal, Paul Fullerton pleaded no contest to misdemeanor possession of marijuana for sales and sale of marijuana. All remaining felony charges, including those against Maricel, were dropped. Fullerton maintains he did nothing wrong and only took the deal to make the rest of the charges go away.

It was far from the end of their troubles, though.

Fullerton had to wear an ankle bracelet for 90 days, but part of the sheriff's department conditions included not using marijuana. Instead of returning to prescription pills, Fullerton found a private monitoring company that would allow him to continue smoking marijuana, but he had to drive two hours each way to Oakland to get to his regular appointments and pay $4,800 for the pleasure.

Despite the charges against Maricel Fullerton being dropped, the case also impacted her career as a vocational nurse. Maricel was banned from working in any state-licensed facilities after a YONET officer appeared at her administrative hearing and testified against her.

And there was still the matter of the Fullertons' money, which had been seized through civil asset forfeiture—a practice that allows police and prosecutors to seize property suspected of being connected to criminal activity, even if the owner isn't convicted or even charged with a crime.

"They seized every single asset that I had," Fullerton says. "Every single cent. I had to borrow money from my mom to get medication for my spinal injury."

To get their cash back, the Fullertons had to prove in court that the money was not connected to drug activity. They eventually were able to account for $53,000 out of the $55,000 seized. The remaining $2,000, they say, was partly vacation savings and partly from the private sale of some used car parts, but they agreed to settle with the D.A.

California passed an asset forfeiture reform bill in 2016 requiring law enforcement to obtain a criminal conviction in forfeiture cases under $40,000. It also requires more detailed annual reporting from the state attorney general's office on forfeiture activities.

However, the numbers for Yolo County don't appear in the attorney general's latest report. Local district attorneys and police departments are not required to participate in the report, and the Yolo County D.A. was one of eight across California that chose not to.

Bargenquast, whose firm, Tully & Weiss, has handled numerous similar marijuana cases, says the attitude among California law enforcement about marijuana is changing, but more education and training is needed.

"We're slowly coming into the paradigm where business shortcomings are treated as business shortcomings, not cartel activity, but baby steps," she says.

"You just have way too many individuals who remember being called heroes and good ol' boys for clearing cartels and irresponsible grows out of national forests, and now they are treating patients or licensees the same way instead of acknowledging they're the citizens they're sworn to protect and serve," Bargenquast continued.

The Yolo County District Attorney's office did not respond to a request for comment. However, Yolo County prosecutor Amanda Zambor told the Davis Enterprise: "After a lengthy financial investigation we were only able to meet our burden of proof on a portion of the money being illegally obtained. In these cases it is often challenging to follow the money trail when there are numerous businesses with poor financial record keeping."

The Fullertons are still seeking the return of their personal electronics, firearms, and 22 pounds of marijuana from the collective Fullerton belongs to, according to the Enterprise.

In the meantime, Fullerton says Lil' Shop of Growers is still up and running, and in fact doing better than ever, although they are still digging themselves out of a hole two years later. But it permanently affected how the Fullertons thought about law enforcement.

"It ruined my whole trust with police officers," Fullerton says. "My daughter is eight now, and she is scared of police officers now. I don't want my daughter to be scared of police officers, you know? It's just a very disheartening."

Show Comments (44)