America's Trade Deficit Is Still Growing

And that's just fine.

Judging by President Donald Trump's favorite metric—America's trade deficit—he is losing his trade war.

Luckily, trade deficits don't matter too much.

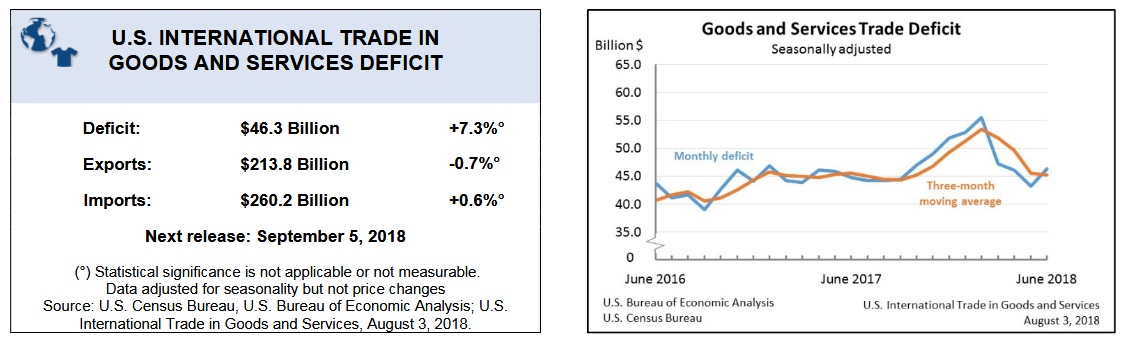

According to data released Friday by the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, America's trade deficit rose to $46.3 billion in June, up from $43.2 billion in May. A trade deficit is the gap between the amount of goods a country exports and imports—the amount it "sells" versus the amount it "buys"—and June's increase was driven by a less than 1 percent uptick in imports along with a comparatively small reduction in exports.

Trump worries a lot about the trade deficit. He's argued that America's trade deficit is such a threat to domestic manufacturing that it justifies an expensive trade war. In announcing tariffs targeting Chinese goods in March, Trump specifically pointed to America's trade deficit—"it's out of control," he said at the time—as one of the justifications for the bellicose trade actions. Going back to his time as a presidential candidate, Trump has singled out the trade deficit as a serious problem, pointing to it as evidence that China is "killing us" on trade. As president, Trump has made reducing the trade deficit a main policy goal, asking not only Chinese officials but also those from the E.U. and Canada (a country with which America has a trade surplus) to reduce their deficits by buying more American goods.

Politically, Trump has used the trade deficit as an easy way to signal his support for blue collar workers and to justify protectionism. Economically, though, there's really not much reason to worry.

In fact, a rising trade deficit can be a good thing.

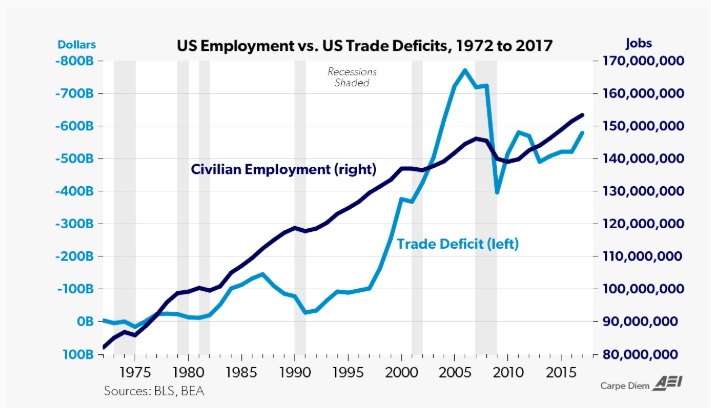

"Despite the false narrative of rising trade deficits leading to U.S. job losses, the exact opposite has been true for nearly the last half-century," says Mark Perry, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute and editor of the think tank's Carpe Diem blog. "Increases in the U.S. trade deficit are associated with rising, not falling, employment levels in the U.S."

It's also worth keeping in mind that the trade deficit isn't something that the leaders of two countries can really negotiate. Sure, governments can impose policies that favor or disfavor trade, but the existence of a trade surplus or deficit is the result of millions of individual decisions made by businesses and consumers in the United States and China.

"People typically forget that the imports that make up the U.S. trade deficit are, like all American imports, goods and services that Americans voluntarily purchase—meaning, goods and services each of which is judged by its American buyer to be worth more than the money paid for it," writes Don Boudreaux, an economist at the Mercatus Center, a free market think tank based at Virginia's George Mason University.

None of those exchanges are forced. American consumers and businesses voluntarily trade their dollars for imported goods. Cutting off that trade, Trump has argued, would "save us a hell of a lot of money," but that really misses the point. You'd save a hell of a lot of money if you didn't buy groceries every month, but you probably wouldn't be better off.

As long as the national economy remains strong, America will likely continue to run a trade deficit and an investment surplus—the result of personal consumption being high and the United States remaining an attractive place for investments. Indeed, the trade deficit essentially disappears if you also consider foreign investment in America as a form of trade, which it really is.

Trump's continued obsession with the trade deficit remains a bit of a mystery. It could be, as Reason editor-in-chief Katherine Mangu-Ward speculated on yesterday's edition of the Reason Podcast, that Trump fails to understand the distinction between the budget deficit and the trade deficit. This actually makes a lot of sense, particularly in light of the president's bizarre tweet over the weekend suggesting that tariff revenue could be used to pay down the national debt. After all, tariffs generate tax revenue and tax revenue is what you need to reduce the deficit—the budget deficit.

But economists mostly agree that tariffs won't do much of anything to reduce the trade deficit—though tariffs could have a secondhand effect on the trade deficit if they become severe enough to slow the economy as a whole and reduce consumer spending, which is the thing that really drives the trade deficit.

"A country is far more likely to run a trade deficit when its economy is booming and personal consumption is high," writes Daniel Drezner, a professor of international politics at Tufts University, in The Washington Post. "If Trump really wanted to shrink the trade deficit, he would push to revoke his own tax bill. But he really does not want to do this."

Unfortunately, a widening trade deficit combined with Trump's apparently faulty understanding of what's driving the trade deficit could be a formula for an escalating trade war—a war that could do a lot of damage without accomplishing what the president wrongly thinks it will.

Show Comments (184)