What We Talk About When Talk About Russian Meddling: Talk

When Americans do it, it's called participating in democracy. When Russians do it, it's called undermining democracy.

Donald Trump has a history of questioning Russia's involvement in efforts to influence the 2016 presidential election, presumably because he bridles at the notion that his campaign colluded with the Russians and the implication that he might not have been elected without Vladimir Putin's help. Trump seems to have trouble separating those three issues, which helps explain why he condemns special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation of Russia's election-related activities as a "witch hunt" and wants Attorney General Jeff Sessions to shut it down. It may also explain why Trump described Russian-sponsored Facebook ads as part of "the Russia hoax." Yesterday the White House tried to compensate for such comments by staging a press briefing in which five national security officials offered a decidedly more alarming take. Rather too alarming, if you ask me.

"Our democracy itself is in the crosshairs," Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen warned. "Free and fair elections are the cornerstone of our democracy, and it has become clear that they are the target of our adversaries, who seek…to sow discord and undermine our way of life." FBI Director Christopher Wray said "malign foreign influence operations" are "targeting our democratic institutions and our values." This "information warfare," he said, is intended to "sow discord or undermine confidence."

National Security Adviser John Bolton described Russia's "meddling and interference" as "aggression" against the United States. "The Russians are looking for every opportunity, regardless of party, regardless of whether or not it applies to the election, to continue their pervasive efforts to undermine our fundamental values," Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats said. He explained that "Russia's intent" is "to undermine our democratic values, drive a wedge between our allies, and do a number of other nefarious things."

According to the Trump administration, Russia is waging "information warfare" that threatens to destroy "our way of life," "democracy itself," and "our fundamental values." Either that, or the whole thing is a hoax. I am inclined to think the truth lies somewhere in between. As Coats mentioned in passing, "Russia has tried to use its propaganda and methods to sow discord in America" for "decades." Somehow our democracy and way of life have survived. To put the matter in perspective, it helps to distinguish between three kinds of activities that fall under the heading of Russian "meddling and interference."

Manipulation of vote counts is the most serious threat, but it also seems to be the most remote. "All the states realize that securing their election systems—both administrative systems and voting machines—is a high priority," Charles Stewart III, an expert on election administration at MIT, tells The New York Times. Stewart "said computer systems and voting machines were now probably the most secure part of the election infrastructure, thanks in part to a stepped-up effort by Homeland Security officials."

The next most serious problem is the hacking of computer systems used by politicians and parties. That sort of intrusion is (and ought to be) a crime, but it's not clear that it undermines democracy in any meaningful sense. As Putin himself has pointed out, when Russian patriots (operating totally independently from the Kremlin, mind you) steal emails from the Democratic National Committee or Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman and post them online, they are disseminating accurate information that may be of legitimate public interest. Even if you don't share that perspective, candidates and campaigns obviously have a strong incentive to avoid embarrassing revelations like these by improving their cybersecurity.

The third kind of meddling is the most amorphous, the hardest to stop, and the one that least resembles an act of aggression. As Wray noted yesterday, "There's a clear distinction between, on the one hand, activities that threaten the security and integrity of our election systems, and, on the other hand, the broader threat of influence operations designed to manipulate and influence our voters and their opinions." The FBI director meant that the defenses against these distinct forms of interference are bound to be different, but the two threats are also morally different. While one violates people's rights (by trespassing on and messing with their property), the other may amount to nothing more than political discourse.

That sort of activity—creating Facebook pages, organizing rallies, running online ads, tweeting commentary—is not ordinarily described as malign or nefarious, and it is indisputably protected by the First Amendment. When Americans do it, we call it participating in democracy. When Russians do it, we call it undermining democracy.

The influence operation described in the federal indictments unveiled in February and July did involve various types of fraud and dishonesty, including social media accounts created under phony identities, Russians posing as Americans, and (in some cases) the dissemination of fake news. But the essence of what these operatives did was still speech. That is how they sought to "sow discord": through messages that people were free to consider or ignore, believe or dismiss, accept at face value or check, take to heart and act on or skim and forget. If that is "aggression" or "warfare," so is any speech that aims to persuade people or reinforce their pre-existing beliefs.

It's true, there is plenty of stupid, illogical, ugly, and misleading stuff in the Russian-sponsored messages that have been publicly released. But there is plenty of stupid, illogical, ugly, and misleading stuff in the messages manufactured by Americans right here in the USA. Why not focus on the content of the speech, rather than the nationality of the speaker?

Even benign speech can take on a sinister cast when it is linked to people who live in other countries. Facebook recently deleted a bunch of pages after finding evidence that they were created by foreigners pretending to be Americans. One of those pages was dedicated to organizing and promoting a counterprotest against a white supremacist rally next week in Washington, D.C. The real activists who are participating in the event are pretty pissed at Facebook's ham-handed censorship. "There wasn't much on the page before we were added," one of them told The New York Times. "The content, when it was taken down, was all from us."

This is the sort of thing you can expect when politicians start demanding that social media platforms help protect American democracy from ads suggesting that a vote for Hillary Clinton is a vote for Satan. "It's an extremely dangerous situation for free speech when politicians are screaming at web platforms to 'do something' about a problem that is difficult to address," Evan Greer, deputy director of Fight for the Future, told the Times. "Censoring an anti-Nazi protest was a particularly egregious example of collateral damage."

Does an anti-Nazi protest "sow discord"? I guess so, and by Nielsen et al.'s logic it represents a threat to democratic values.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Saw that "libertarian leaning Senator Ron Wyden" is the biggest cheerleader of censorship of the internet based upon a conspiracy theory and dubious illegality.

(LOL)

Right? Wasn't he all about freedom from being spied on online by the government just a year or two ago? Talk about a complete 180.

I don't know. Wyden was never all that particularly good on speech or just about anything. He was only slightly better than most. Tulsi Gabbard in the House was always more "libertarian leaning" from a Democratic perspective

"Free and fair elections are the cornerstone of our democracy." I can't register as a Libertarian in PA.

When the state can attempt to limit citizens' political speech simply due to its close proximity to election day, assaulting speech rights from non-citizens is nothing.

Donald Trump has a history of questioning Russia's involvement in efforts to influence the 2016 presidential election, presumably because he bridles at the notion that his campaign colluded with the Russians and the implication that he might not have been elected without Vladimir Putin's help.

This sentence is a mess. I blame the word 'bridles'.

"Bridles" saddled that sentence with too much weight to overcome. "Notion" cinched it as a lost cost.

cause, not cost....

"Bridles saddled that sentence..." i see what you did there.

Not to mention "cinched it".

Information warfare is and always has been a part of warfare. The first amendment is my favorite amendment, but its existence doesn't render propaganda impotent. It emphasizes the power that speech can have, in fact.

If you are nonchalant about the threat, perhaps glance over in the direction of the White House and see what they saddled us with. Without much more effort than speech directed at the right dupes.

If you took all the stupid things Tony has believed over years--just because he read it on some stupid website--and stacked them all on top of each other, it would reach halfway to the moon.

Tony writing about propaganda victims is ridiculous. I've never in my life seen a bigger propaganda victim than Tony. The stupid shit he says every day with firm conviction is just as bad or worse than anything the Russians might have put on Facebook.

For pity's sake.

Tony is all-in on the Russia conspiracy theory. He gets it from highly reputable sources like CNN. If you express doubt, well, you're just anti-media-free-speech.

He's demonstrated every day for years that he's the biggest propaganda victim any of us have ever seen!

The idea that Tony and company will save us from propaganda is ridiculous. He doesn't have a critical thinking bone in his body.

Well, the thing is that once you're taught goodthink you are free of choice and autonomy which for some is freedom of a sort.

He might not have a critical bone in his body, but his body gets critically boned quite often.

No doubt Tony would be quick to apply the Constitution to illegal immigrants, but heaven forbid a Russian tries saying something.

Step 1: Don't put things in email that would jeopardize your candidacy.

Step 2: Don't give your passwords to Russians

Step 3: Don't piss off your Bernie-bro IT staffer by screwing his candidate.

Step 1A: Don't outsource your IT to Pakistani ISI Agents

Tony, consider this:

The "Russian meddling" narrative is itself propaganda.

So Bob Mueller is a victim of propaganda? Or is he the ringleader of a vast conspiracy on behalf of... someone.

Do you even listen to the news? John Brennan, Michael Hayden, James Clapper. Mueller is as bent as fuck. When he was US attorney in Mass. he pressured the Mass. parole board to not grant parole to 4 people that he KNEW were innocent (his local FBI framed them for Whitey Bulger)!!

Bob Mueller is (with the afore mentioned) a CREATOR of propaganda.

Tony|8.3.18 @ 4:02PM|#

"...The first amendment is my favorite amendment, but..."

You need say no more at all, shitbag; the "but" tells us exactly how pro A1 you are.

The 2nd Amendment is my favorite Amendment. Period.

What do you like so much about militias? It's the communal showering, isn't it?

Perhaps you should read the entire amendment, you low forehead.

Stewart said, "computer systems and voting machines were now probably the most secure part of the election infrastructure

Now? So, in 2016 the most secure part of the election infrastructure were party servers or lexan voting booths?

Intent matters.

Let's say I got to a protest against Hane's new blended-fabric boxer-briefs (they're against Leviticus, don'tchaknow). At this protest, I shout various things, as one does at a protest, and one of the other guys there gets so into it he throws a bottle at a cop and a riot starts.

If I'm sincere, and just there to protest, then that's one thing.

If I went there with the intention of goading people into starting a riot, that's another thing.

Intent matters. In this case, the vast majority of the Russians we're talking about don't sincerely care about our issues, they aren't good faith actors participating in debate, they are here to rile things up and cause problems. They are trying to goad Americans into starting a riot.

Whether this rises to criminal action is a separate topic. But on a moral and ethical level, good faith participation in public discourse and debate is very different from going in with the intention of starting a fight.

Intent doesn't matter for shit.

The things people say are persuasive or not regardless of the intentions of the people who say them--likewise their truthiness.

Meanwhile, we're mostly talking about qualitative criteria anyway--and there's nothing wrong with that!

I have a qualitative preference for freedom. I also like rocky road ice cream. If I care more about religious rights than gay rights or more about gun rights than whether Donald Trump bragged about groping women, there's nothing objectively wrong about that. This is the way most people come to make their decisions on whom to vote for. It's also how they pick whom to root for in the Super Bowl. So what?

All choices have a qualitative component, and the idea that our betters can make better qualitative choices for us on our behalf is probably the mother of all elitism. It's also horse shit.

Swing voters in swing states preferred Trump to Hillary for their own qualitative reasons, and the intentions of Russian Facebook trolls doesn't matter any more than the qualitative preferences of elitists.

Which is why no one draws a difference between a troll and someone they just disagree with, why we don't even have the term "good faith debate", why we have no distinction between someone that is merely wrong and someone who is lying, and so-on.

So, foreigners have no right to free speech in the US, but do they have a right to migration?

Just trying to assess the logic here

You are trying to asses the logic on a web site comment page?

What is the last digit in PI?

From the perspective of the law, policy, practice, etc., intentions don't matter for shit. The question isn't even people's integrity.

What is the question?

Are you saying that foreigners shouldn't be allowed to comment on Facebook about politics unless their motives are pure?

Are you saying that election results shouldn't be respected if the voters read the opinions of people who don't have our best interests at heart?

That's horseshit.

You're wrong about intentions, Ken, from the perspective of the law, policy, etc. Don't you remember that Comey said Hillary's server problem didn't rise to the level of a crime, because she didn't intend to break any law? i mean, that's what he said wasn't it? That no prosecutor in America would take the case, because there was no intent? i mean, he should know, right?

"Which is why no one draws a difference between a troll and someone they just disagree with, why we don't even have the term "good faith debate", why we have no distinction between someone that is merely wrong and someone who is lying, and so-on."

Yes, we actually do. That you don't is another issue.

Intent is all that matters to progressives. If something has adverse effects or results in failure, say the war on poverty, it's cool: they had good intentions!

A side benefit for progressives is that they are the only ones who get to determine intent - thus the same statements can be racist or satirical based on ehat progressives tell us the speaker's intent was.

To progressives, yes.

They'd herd us all into work camps if you could convince progressives that the motives of their overlords were pure--and the victims didn't have good intentions at all.

Americans are pretty good at starting riots from their own goading. Like Sullum asked, why does the nationality of the speaker make a difference? Maybe it's just easier to scapegoat a foreign power?

They are trying to goad Americans into starting a riot.

Inciting a riot is already a crime. It's the only crime David Duke has ever been convicted of. Are there any riots that these investigations are being based off of?

So... The Boston Tea Party was illegitimate?

Holy cow, this verges on mentally deranged.

What you're really saying is there needs to be someone who can mind read people's intent. I mean, what the F are you talking about? How can you ever know someone's intent? Are you relying on everyone coming out and telling you just what their intent is or are you going to guess, or simply ignore them if you think they're lying. This is the reason for the 2nd amendment - so people like you will be prevented from stifling people's speech simply because you THINK they have bad intentions.

I don't even know what the hell your example has to do with what you even said. You are their to speak, the other guy came to throw shit. The guy throwing whit should be arrested. You shouldn't. Is it really that hard to comprehend? \

Take away social media and what exactly did "Russians" do?

Because no one should give even a very tiny damn about anything on social media.

Only the government does. This is nothing more than an attempt to gain control over the internet and over these corporations.

Every American should find the suggestion insulting that our president was chosen because of Facebook ads. Underneath it all, we're still talking about the elitist left and their inability to come to terms with the fact that the American people don't hate themselves as much as the elitists hate them.

And the elitist left does hate the American people. They hate them for being white, blue collar, selfish, Christian, heterosexual, etc. and, especially, for not sharing the qualitative preferences of the elitist left. They even hate Americans for being patriotic. It's sickening.

When the Democrats win the White House again, all this talk about meddling in elections will evaporate, too. The American people picked the wrong president according to the elitist left, and they've been flailing about looking for explanations ever since. So people tried to influence you on Facebook, so fucking what?

Even if no foreign government had ever bought an ad, the American people would still have known that Hillary Clinton was a crook, and she represented the elitist left, which hates the American people--for being American.

And she'd rather attend fundraisers in Hollywood than fish fries in Madison.

According to the Trump administration, Russia is waging "information warfare" that threatens to destroy "our way of life," "democracy itself," and "our fundamental values."

So Trump is claiming that Russia stole the election? WTF?

When cops make child porn, it's called getting probation.

Former Deputy Who Made Child Porn Gets Probation Instead Of Prison Time

Surely that was the first and only time he ever did that. Surely he didn't have more images and didn't download any others from the FBI. That must be why he got probation like anyone else would.

The New York Times did more destructive pro-Russia propaganda in a single year (1932/33) than all the Russian sponsored social media messaging in the history of the Internet.

NYT's Duranty and Reed actually knew how to manipulate American public opinion. So much so that Hollywood has made romantic dramas about their devotion to the cause of communism.

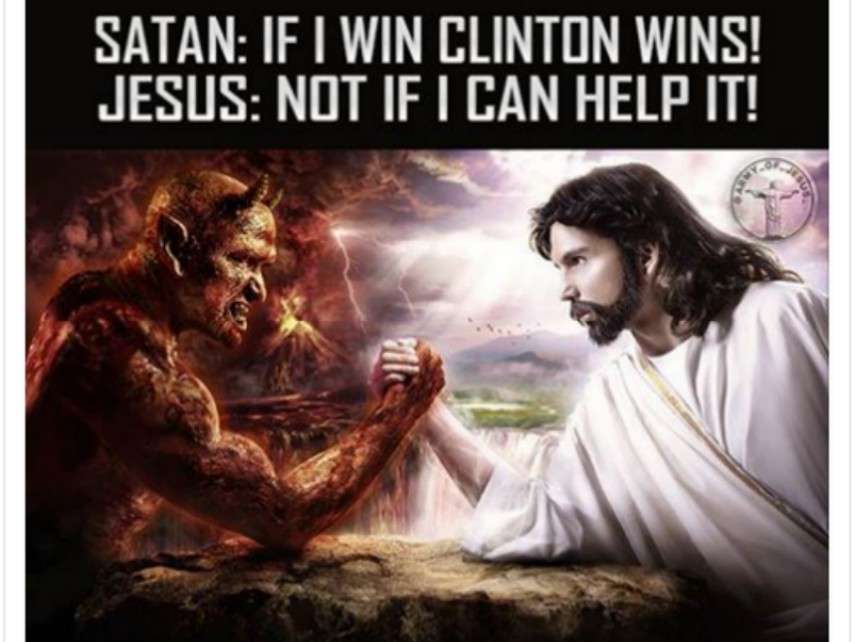

Compare with Russia's propagandists who create Jesus v The Devil armwrestling posters to oppose Hillary.

Russia's use of social media is just the 21st century equivalent of Radio Moscow.

Of course the Russkies are trying to manipulate American public opinion. So are the Wahhabis in Saudi Arabia and the ChiComs in Beijing. The Chavistas in Caracas used Joe Kennedy to buy American public opinion with subsidized heating oil. The most successful of them all at manipulating American public opinion are the Israelis, who are very adept at targeting segments of the American population and the political class.

Back during the Cold War days, the Russkies used to jam VOA and RFE broadcasts whereas Americans were confident enough to let the commies broadcast to the US without interference. The most significant difference between the Cold War and now is not with the Russians or with the technology: on the contrary, it is the fact that the American political elite is so unsure of itself and its own legitimacy that it fears Russian propaganda is more believable than its own, often fake, news.

The thing is that no one gets manipulated unless they want to believe whatever opinion is being pushed. So the ability of these kinds of things to actually change public opinion is pretty small. At best they just give people an excuse to believe something they already believed anyway.

Indeed. I use to be a shortwave listener in junior high and high school, and occasionally tuned in to Radio Moscow and the other commie broadcasts in the mid-60s to the mid-80s. The only Americans who believed their propaganda were devoted Marxists, the sort that P.J. O'Rourke wrote about in "Ship of Fools" (about a 1982 "peace cruise" on the Volga River that was sponsored by The Nation magazine.)

Commie propaganda was really lame, every bit as lame as Jesus arm wrestling Satan. They were even bad when they pretended to report straight news; VOA/RFE were always pro-America, but they were pretty straight with the news. I am reminded of the old Cold War commie propaganda when I watch CNN and MSNBC (450 stories on Stormy Daniels versus zero stories on the ongoing war and humanitarian disaster in Yemen in the past year.)

Unlike his commie predecessors, Putin has been either extraordinarily sophisticated or insanely lucky with the Russkie propaganda program, but its success has nothing to do with the quality of social media propaganda per se. Instead, the Russkies used comparably lame propaganda to drive the American losers in the 2016 election -- which includes a majority of American mainstream media and Hollywood as well as the DC bureaucracy that went 95% Clinton -- batshit crazy, and thereby polarized the American public to an extent not seen since 1865.

Well said, Cato.

Though I'll note that Soviet Union does not equal Russia. It is common to equate the two, but that obscures a very important point: the true allegiance of those who spilled for the USSR and now decry post-communist Russia

*shilled, not spilled

The "Russians" created that devil vs jesus poster?

Dang. How do I take back my vote?

This is absolutely true--

From the left.

"When Americans do it, it's called participating in democracy. When Russians do it, it's called undermining democracy."

Unless the Americans in question were criticizing Hillary Clinton. Basically anything that is bad for her is called undermining democracy

*bad for her career

Sounds like you're trying to undermine democracy

Thank you for noticing

I've been waiting for over a year for somebody to explain one thing the Russians did to "meddle with" the election. All I know about is that Russians supposedly helped publish real truthful emails about the DNC insiders trying to help Hillary beat Bernie. They meddled with the election by revealing the truth?

Are Facebook ads, which could have been bought by anybody, really meddling? I've never seen one. They must be powerful stuff.

Being a voting U.S. citizen, if I talk to a Russian citizen and they have an opinion about politics, should I cover my ears and say "LA LA LA! I CAN'T HEAR YOU"?

Everybody should vote for Kronos in 2020.

If I turn out to be a Russian posting through a proxy, have I just attacked the election process?

Is there really nothing else?

Back in October, 2016, on the facebook, Russian robots tried to brainwash me to vote for Trumps.

Fortunately my anti-brainwashing software blocked them and I was able to vote for Gary Johnson 3 times.

Unfortunately, he still lost.

Back in October, 2016, on the facebook, Russian robots tried to brainwash me to vote for Trumps.

Fortunately my anti-brainwashing software blocked them and I was able to vote for Gary Johnson 3 times.

Unfortunately, he still lost.

According to several highly placed anonymous sources in Russia, Gary Johnson voted for Hillary.

The supposed high tech libs here still cannot get it -the INTERNET RESEARCH INSTITUTE was simply a commercial click bait operation. They used political ads (as well as non political, like pictures of puppies) simply to get clicks on Google ads or whatever and make a buck. There were no spies there, except maybe the last few months when the CIA infiltrated the business. It was simply to make money, not "sow dissent" or "undermine our democracy". The owner of IRI had been doing that in Russia and simply decided to expand to US and got caught in a Trump Derangement Syndrome shitstorm. Sheeeesh!

Any democracy (even the ones that are republics) that can be brought down by a tweet or a post, deserves it.

Russia was our ally during the last numbered war.

Russia, as a member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was our enemy during the cold war.

Russia is our ally and enemy in the middle east.

What the hell, let them have a facebook account. No one reads that drivel anyway.

I'd be more worried about the Russian trolling if it was more effective, like it used to be back in the commie days.

Even then, they had more success with infiltrating "well intentioned" movements than in getting their people elected.

Interesting that when Manning and Snowden released U.S. government emails and other documents to Wikipedia, they were heroes to the Left, but when Russian hackers released DNC emails to Wikipedia, they are interfering with democracy.

Believing that Russians gave the election to Trump is ostensibly what the Russians want, since it suggests democracy was undermined.

One would think people wouldn't want to jump to that conclusion, unless they had a very self-serving reason.

Ah, fuck it: let's just embrace political censorship and get it over with. For the sake of democracy. Because democracy is apparently the bestest way to make the most awesome decisions, and completely fragile as fuck.

Hey, what about all the Chinese medding? Why doesn't some one some where talk about that? The Chinese have basically owned the US Government lock stock & barrel since The Year of the Rat 1996. So, what gives?

The OPM records hack was the greatest intelligence breach of all time.

"Here, have all our personnel records"

The media yawns.

But if Russians tweet something, it's time to launch the nukes!

Foreign Powers don't have First Amendment rights to seek to influence the American electorate and therefore American policy.

Our Constitution does mean the measures the government can take to resist their IO campaign have limitations, but that doesn't mean we should ignore the threat or fail to take those measures we can.

Free speech is about the right to hear and read, not just the right to speak.

RT is generally more credible than our MSM, as they often have no skin in the game for many stories, and so can play them straight.

Classy picture of Jesus and Satan arm wrestling for politics.

TDS and general sneering at the "bitter clingers". What else is Reason for, after all?

Hey Sullum, why don't you put your big boy pants on and try that with Muhammad?

I've said it before and I'll say it again: it's awfully hard for Russian (or other) propagandists to influence the words that candidates spout from their own mouths.

there is a great deal of misattention played to the social media aspect of the russia story, & it is worthwhile to remind ppl that there is very little evidence to assume that posts on social media or even advertisements by evil doers have any appreciable impact on at least presidential elections.

with that said, the notion that state-run election IT infrastructure is absolutely ludicrous. im not familiar with the mit "expert" quoted here - and i cant get past the nyt paywall atm to view the context. if in fact he is attempting to argue that recent efforts by homeland security have resulted in any change to how voting machines will be run in the midterms that will have an appreciable impact on their systemically insecure & incompetent design & operation then the expert is factually wrong.

if the expert is attempting to maintain that the sort of IT infrastructure powering elections in, say, louisiana are more secure than the pen & paper ballots they replaced, then again the expert is factually wrong.

anyone who would make either claim is either incompetent on basic issues of network/software security, unfamiliar with the garbage on offer now & in the recent past by vendors in this field, or arguing in bad faith / lacking intellectual honesty.

the only " IT professionals" that I have seen willing to go on the record claiming that voting machines are anything other than an absolute travesty are individuals working for one of the vendors or for one of the state election boards. the machines are abysmal failures in design, manufacture, implementation & administration. security is only one of the many problems - plenty of these machines fail to reliably count & have for years; of course w/out a paper ballot to audit against & state laws only mandating recounts for certain types of outcomes, basic failures are almost certainly much more widespread than currently known.

russia is almost besides the point: voting machine hw & sw fails to meet basic industry standards for competency & fails at any point objectively & seriously testec