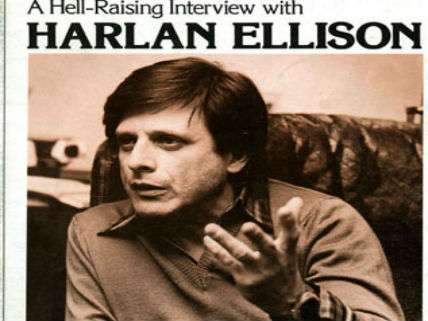

Harlan Ellison, R.I.P.

The science fiction maverick helped fill generations of fans with a winning sense of courage and rebellion.

Writer Harlan Ellison died today at age 84. In the pre-internet age when available culture was far more limited, certain figures crossed a cultural blood-brain barrier bridging various tribes attracted to underground or "rebellious" ideas. Ellison was prominent among them, earning many fans in the libertarian space without himself being a libertarian in a conventional sense.

His influence and success in the fields of science fiction (written and filmed), TV screenwriting, fantasy, and mystery are summed up well in this essay about him on Barnes & Noble.com. What Ellison sold as a public figure in his many colorful essays, interviews, and public appearances (beyond the fascination of his many dozens of great, vivid, pulsing, high-energy and high-concept fictions that underlay why we cared about him in the first place) was righteously pugnacious rebellion.

This made Harlan for many young people of my generation (and the one before and after) with a yen for genre fiction and fandom a compelling and convincing voice selling the notion that things were deeply and fundamentally wrong that needed fixing. His bill of particulars against consensus social reality might not have been the same as a young libertarian's, but the overarching spirit of corrosive critique and the blazing spirit of the formerly bullied who bootstrapped himself with often wild bravery to fight things he thought were wrong, from civil rights abuses to perceived mistreatment of writers, his image of a sensitive gut-fighter refusing to be stepped on, was inspirational, especially to an adolescent or pre-adolescent fan mind.

Ellison would reject the notion, but having read most of his work when I was 11-16 and having re-read a chunk of it recently, I think in literary terms he's best considered a superlative "Young Adult" writer, one whose endless bevy of ideas that were just, in youthful parlance, supercool combined with the moral imagination of a wounded adolescent (that's no insult) make him a writer the smart and impassioned young will be rediscovering with awe and wonder for a long time to come. His themes were often "adult" in an R-rated way, but his tone and style I think mark him best as a writer to fall in love with in your teens. While as a reader gets older and wiser the specifics of Ellison's standards might become more open to question, his tone and character helped imbue a real sense that high standards when it comes to aesthetics and ethics and living were important and worth struggling for. If he was a bit of a show-off, he was a show-off with heart and purpose.

In whole, and despite many choices public and private that the sober might find objectionable, Ellison was overall a Good Thing for the world. Harlan the fiction writer and Harlan the public character were both justly heroes to many. (Cory Doctorow at BoingBoing today has a heavier take on balancing the positive and negative aspects of Ellison's public behavior for those who admired him as a writer or public figure but couldn't approve overall his occasion old-school rudenesses and wrath.)

Ellison was also a great booster for his adopted home city of Los Angeles, one of its most passionate and loving advocates, and he made himself widely available as a public figure around the city he and I shared for 21 years, at readings (from book stores to hot dog stands), film showings, and just hanging around as a fellow customer at the local science fiction book store in Sherman Oaks.

While he fought many public battles of a sort an outsider might find incomprehensible against the "fan mentality" he was also very much steeped in fandom and its passions and style, historically and emotionally. His sense of the fanhood from which he arose, in addition to a core sense of decency often swaddled in superficial meanness, I suspect inspired him to be as kind and open as probity allowed (and beyond—he listed his own home phone number in one of his books and continued answering it) to his fans, even as he suffered fools ungladly and understood a fair amount of comedic ballbusting was part of what one came to Harlan for.

Among many brief encounters with him, I've always treasured that while sidling down the aisles toward stage to talk after a Writers' Guild Theater showing of the 2008 documentary about him, Dreams with Sharp Teeth, he stopped to notice me reading a book waiting for the show to start.

"Whatcha readin'?" he asked. I shyly showed him the old paperback of Daniel Bell's The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the 50s in my hands. He kept engaging me, for no reason other than to give a fan a thrill, for a few more rounds, in which I recall the humorous use of the term "poindexter" aimed at me. I loved it and he knew it.

Last time I saw him was a classic Harlan moment, combining commerce, fan service, and tsuris: an appearance at the Glendale Vintage Paperback Show a few years back to sign books, in which he managed to with his own refusal to rush himself or cheat fans out of a moment even for a line of hundreds, turn what could have been two hours of signing into a long day's journey into night of aggravating waiting, a "Harlan story" that all there will tell for years, no doubt.

The last time we wrote about Harlan at Reason, when he won the Prometheus Hall of Fame Award (given by the Libertarian Futurist Society) in 2015 for his classic short story "'Repent Harlequin!' Said the Ticktockman" Ellison made a YouTube video (posted below) in which he read an excerpt from what I wrote, referring to me as an "email internet…guy."

Regardless, that my words left Harlan Ellison's mouth will remain a proud memory and in some sci-fi sense I hope echo back in time to the 12-year-old me who actually used his published home phone number, and was gently upbraided by Ellison, who actually came to the phone for the weird kids, for bugging him for no good reason.

"If you want to call me a libertarian, I have no objection," Ellison said in the video below. As I wrote when he copped the Prometheus, Ellison

delighted in sticking up, in fiction and life, for those squashed by societal repression. He saw himself as a rebel conscience for his community and culture. He once said his preferred self image was a cross between Jiminy Cricket and Zorro. …."Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman," begins with a great quote from Thoreau's "Civil Disobedience" about how those who serve the state with their consciences are "commonly treated as enemies by it." (I'd prefer the locution, serve their community by their consciences, but Thoreau is Thoreau.) [and the story's] inspirational message of individual senses' of life, purpose, and fun defeating grim, crabbed forces of central control acting for an alleged "social good."

That was good enough for this young libertarian, and for young fans of all walks of life who needed a voice of loud, unshakable, colorful, imaginative and energetic courage.

Show Comments (22)