The Good and the Bad of Trump's Decision to Delay Some Tariffs

Trump talks about wanting to reduce our trade deficit with China, but using tariffs to do it might jeopardize America's trade surplus in agriculture.

The White House has decided not to decide whether to slap huge tariffs on steel and aluminum imported from several U.S. allies and top trading partners, postponing the decision until at least June 1 while negotiations on bilateral trade deals continue.

When President Donald Trump announced in early March that he was imposing a 25 percent tariff on imported steel and a 10 percent tariff on imported aluminum, the threat of retaliation from Europe, Canada, and elsewhere persuaded the administration to grant temporary exemptions to several nations. Those exemptions were set to expire at midnight on May 1. South Korea has already negotiated a permanent exemption to the tariffs, and The New York Times reports that similar deals with Argentina, Australia, and Brazil are in the works.

The tariffs have already gone into effect on steel and aluminum imports from China, Russia, Japan, and some other places. That leaves Canada, Mexico, and the European Union in limbo for at least another month.

This decision to avoid a decision is better than one of the alternatives, of course, but it means more uncertainty for American businesses—some of which are already paying higher prices for steel, and passing those higher costs along to consumers, in anticipation of full-fledged tariffs. That stands in "direct contrast" to the Trump administration's goals of reducing tax and regulatory burdens, says Bryan Riley, director of the Free Trade Initiative at the National Taxpayers Union.

"The good news" from this week's non-decision "is that we don't have across-the-board tariffs," Riley tells Reason. "That's good news if you work for a carmaker, or work in construction, or buy goods made from steel, which is basically all of us.

The bad news? "This gives the government additional discretion to pick winners and losers among our trading partners," says Riley.

Trump has often talked about America's trade deficit with China as justification for his tariffs, apparently because he has for decades misunderstood the win-win nature of trade. Now, in his rush to address what he sees as an imbalance between China and the U.S., he risks creating problems for a sector of the American economy where a trade surplus has been the norm for decades.

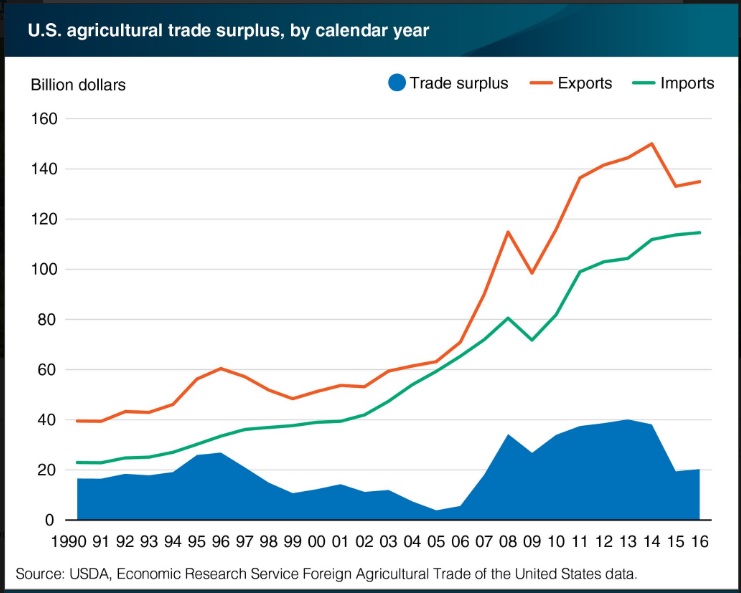

America is one the world's leading exporters of agricultural products. We grow way more than we can eat:

This is good for the American economy. But it's also good for the rest of world. America's agricultural trade surplus means we can feed people who would otherwise go hungry, or at least reduce the cost of food around the globe. To be sure, this surplus is partially the result of other government policies—various farm subsidies—that also equate to picking winners and losers. Still, it should be difficult for a political leader to argue that a trade deficit in agriculture is a threat to the nation's economy and that his people should only eat what they can grow for themselves, even if that means some will starve. Yet this is exactly the sort of error Trump is making.

It's also the reason why American farmers are one of the groups most worried about a trade war. Not only do American farmers rely on a lot of equipment made of steel and aluminum (both of which are becoming more expensive to buy), but they depend on foreign markets being open to the products they grow.

Take soybeans. American farmers planted more than 89 million acres of soybeans this year, and they expect to export about half of the soybean crop. If Europe or China respond to Trump's tariffs by slapping their own tariffs on American agricultural products—as they have threatened to do—American farmers could be left with far more soybeans than they are able to sell. That's a loss both for them and for the people who might otherwise have consumed those soybeans. If trade is a win-win arrangement, trade wars are a lose-lose.

Show Comments (11)