Before People Fretted About Fake Videos, People Fretted About Fake Photographs

Do deepfakes really represent "the collapse of reality"?

Franklin Foer has heard about deepfake videos, and he's worried. His latest chin-stroker in The Atlantic, headlined "The Era of Fake Video Begins," warns that in a world of "almost seamlessly stitched" visual fakery, our eyes will "routinely deceive us." Video manipulations "will create new and understandable suspicions about everything we watch," and figures in the news "will exploit those doubts." Our "strongest remaining tether to the idea of common reality" will fray, and "the collapse of reality" will follow.

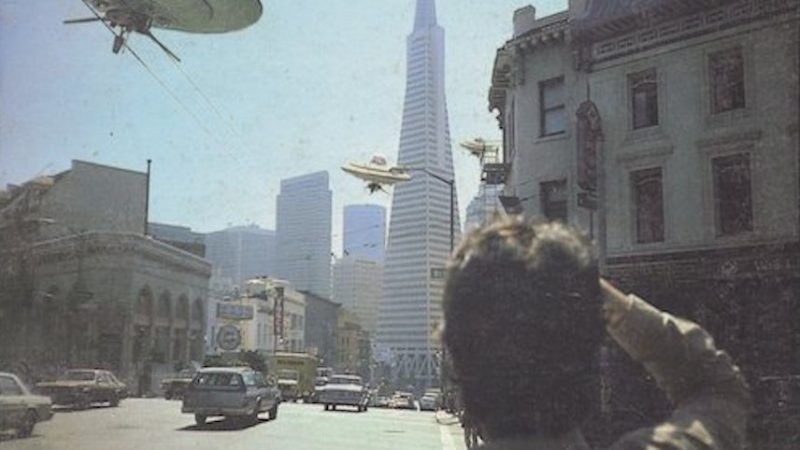

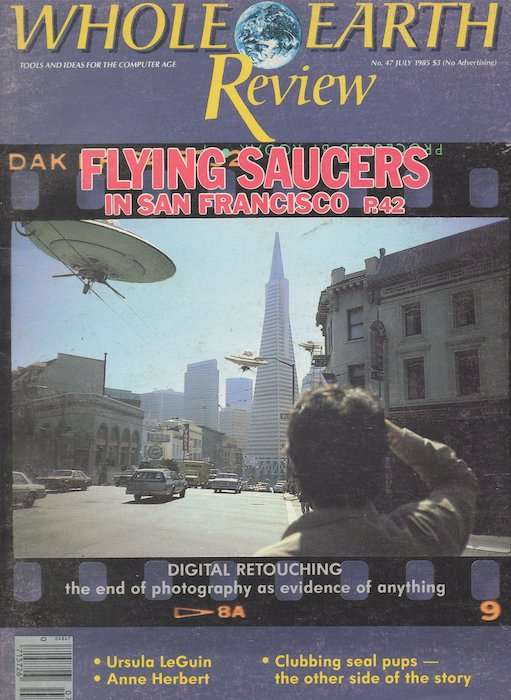

The whole thing gave me deja vu, because I'm old enough to remember when this magazine came out in 1985:

Come for the faked photo of saucers over San Francisco; stay for the story headlined "Digital Retouching: The End of Photography as Evidence of Anything."

Comparing Foer's feature to that old Whole Earth Review is a little unfair, because the Whole Earth article is actually rather good. It's not an essay but a roundtable discussion, with Stewart Brand, Kevin Kelly, and Jay Kinney weighing in on what would happen now that the old laborious photo-doctoring processes were giving way to far faster and easier digital manipulations; between them, the trio has the historical and technological perspective that Foer's story lacks. But like practiced showmen, they open with an attention-grabbing scary scenario:

"Your honor, we cannot accept this photograph in evidence. While it purports to show my client in a motel bedroom with a woman not his wife, there is no way to prove the photograph is real. As we know, the craft of digital retouching has advanced to the point where a 'photograph' can represent anything whatever. It could show my client in bed with your honor.

"To be sure, digital retouching is still a somewhat expensive process. A black-and-white photo like this, and the negative it's made from, might cost a few thousand dollars to concoct as fiction, but considering my client's social position and the financial stakes of this case, the cost of the technique is irrelevant here. If your honor prefers, the defense will state that this photograph is a fake, but that is not necessary. The photograph COULD be a fake; no one can prove it isn't; therefore it cannot be admitted as evidence.

"Photography has no place in this or any other courtoon. For that matter, neither does film, videotape, or audiotape, in case the plaintiff plans to introduce in evidence other media susceptible to digital retouching." —Some lawyer, any day now.

Two things about that monologue jump out. The first is that it sounds a lot like Foer's fears about video manipulations today. The second is that photographs are in fact still used as evidence in courtrooms, with generally agreed-upon standards for when to treat them as authentic. The reasons why they still get used as evidence in 2018 were explained in advance by Kevin Kelly in that same Whole Earth forum:

We've been spoiled by a hundred years of reliable photography as a place to put faith, but that century was an anomaly. Before then, and after now, we have to trust in other ways. What the magazines who routinely use these creative retouching machines say is "Trust us." That's correct. You can't trust the medium; you can only trust the source, the people. It's the same with text, after all. You can print a lie in 100,000 subscriptions and it looks the same in ink as the truth. The only way to tell is by the source being trustworthy. The only way my words are evidence is if I don't lie, even though it's so, so easy to do.

We know what it looks like when a crisis of trust hits the courts, because we've seen it happen in several cities. Thousands of people have been released from jail because particular cops or crime-lab employees turned out not to be trustworthy. Those convictions were not overturned because Americans lost their faith in photographs, or in any other technology. They were overturned because institutions themselves, or members of those institutions, lost public faith.

When people trust institutions, they generally trust the evidence those institutions present. When people do not trust institutions, they find reasons to reject evidence or just to read it differently. It's telling that Foer calls the passing age of trustworthy motion pictures "Abraham Zapruder's world," invoking the amateur cameraman who captured John F. Kennedy's assassination. If you were to select a single example that best demonstrates how even an unaltered, undoctored film can attract a storm of competing interpretations, surely the prime candidate would be Zapruder's much-debated 486 frames of footage. If this is your "tether to the idea of common reality," you need a new rope.

Foer isn't oblivious to the underlying problem, but he approaches it in a backward way:

Few individuals will have the time or perhaps the capacity to sort elaborate fabulation from truth. Our best hope may be outsourcing the problem, restoring cultural authority to trusted validators with training and knowledge: newspapers, universities. Perhaps big technology companies will understand this crisis and assume this role, too. Since they control the most-important access points to news and information, they could most easily squash manipulated videos, for instance. But to play this role, they would have to accept certain responsibilities that they have so far largely resisted.

Having mistaken a crisis of trust in institutions for a crisis of technology, Foer suggests we solve the tech crisis by restoring trust in institutions. Good luck with that.

My expectations are less apocalyptic than Foer's. I don't think video evidence will disappear any more than photographic evidence did three decades ago, but there will be more noise around that evidence. We will figure out ways to navigate through the noise, and those ways will be imperfect, but if we're lucky we'll be clear-eyed about those imperfections. The best we can hope for is an ecosystem of mutual peer review where everyone is fallible and no one is the final authority.

A broad social shift is underway in societies around the world—a point at which modernity starts eroding not just traditional authority but the authorities erected by modernity itself. People like Foer respond to that by longing for the old certainties and the institutional power that protected them, but I doubt it's possible to restore that social order and I certainly wouldn't want to. This has always been a world of rumors, disinformation, and fog. There aren't necessarily more deceptions today than in the past; it's just more dizzyingly obvious that we live in a wilderness of mirrors. As those old illusions collapse, Foer thinks he's watching the collapse of reality.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

...in a world of "almost seamlessly stitched" visual fakery, our eyes will "routinely deceive us."

Apparently someone hasn't yet seen the attempt to remove Henry Cavill's mustache in reshoots for Justice League.

Its kind of funny, these moral panics.

You'd think that anyone familiar with the advent of fake photography would also be familiar with the fact that, so far, the tools and knowledge to *spot* fake photography have kept pace with improvements in ability to fake.

While obviously that won't be the case forever, fake photos STILL aren't good enough to fool decent analysis after all these years and the same will hold for fake video for a decent while too.

And once it doesn't then it won't matter anymore. If you can't rely on video to give a true account then we'll adjust to that new reality.

Yes. I didn't get into it, because the post was too long already, but Flawless Fakery That You Can't Detect is always supposed to be just around the corner. Yet viewers tend to get savvy pretty quickly. The number of people who spot Photoshop's fingerprints is way larger than the number of people who actually use Photoshop.

Anyone remember when people were freaking out about colored printers and counterfeit currency?

And it's one of the oldest memes known to man.

The reason it's always around the corner is flawless fakery requires fusion power, which is always 20 years down the road.

"The number of people who spot Photoshop's fingerprints is way larger than the number of people who actually use Photoshop."

I doubt this very much. It's more likely that those who can spot a photoshopped image are a subset of photoshop users.

Have you seen some of these deepfakes? They aren't remotely convincing even to the untrained eye.

Even Foer felt the need to insert "almost" before "seamlessly stitched."

"fake photos STILL aren't good enough to fool decent analysis after all these years and the same will hold for fake video for a decent while too."

You're being naive. People don't believe faked photos because they've managed to fool expert analysts, they believe them because the images confirm their biases. They wouldn't work otherwise.

Please listen carefully to this bastion of intelligence and sanity.

I'm afraid that willful naivety will carry the day here. But by all means, listen to the bastion.

This is the same thought process used by all the douchebags who think a million stupid Americans were lured into voting Trump because of Russian ads.

Tony's making those claims a few threads down.

Tony is still bitter about deepfake dildos.

I saw that pathetic display. Sad!

That seems to be becoming more and more an article of faith to the progressive left.

We're paying you a compliment though. You weren't some slack-jawed yokel who voted for Trump out of a genuine belief in his fitness for president, because what kind of fucking moron could possibly believe that? You were simply tricked. Happens to the best of us.

Tricked into thinking that Hillary was so bad she deserved to lose, even to Trump?

Not a hard case for anyone to make, Russian or not.

There's one tally mark for slack-jawed yokel.

Heck, we still haven't stopped relying on eye-witness testimony despite the fact that eye-witness accounts are some of the least reliable evidence there is. Just ask Penn and Teller how easily the mind can be fooled into seeing things that just aren't there.

Yeah, the statement "You can't trust the medium; you can only trust the source, the people." needs a few more conditionals.

Apparently, at one point, people were concerned with building houses on sinking sand.

Man, Jesse. That's what I call a total obliteration. They'll be picking up pieces of Foer's dignity all across the landscape until fossil fuels run out.

He really decimated that guy's point.

"There aren't necessarily more deceptions today than in the past"

Of course there are more deceptions today than in the past. More people, more interactions between them and more channels of communication. How could it be otherwise unless you're claiming that people today are somehow less deceitful than our predecessors.

I MEANT PROPORTIONALLY, OKAY?

"OKAY?"

Not really. You have any evidence to back up this claim?

Jesse, don't ever engage with mtrueman unless you like long, pointless back-and-forths based entirely on semantic misdirection, which he will then go on Mexican Blogspot and complain about.

Jesse, follow this sage advice and quit before you blunder into more weaselish inanities.

Weaselish Inanity would be an excellent name for your blog.

There's more where that came from. Keep the faith, dear reader.

There aren't necessarily more deceptions today than in the past

See that word bolded there? That would leave open the possibility that there are more deceptions today, at least in terms of absolute numbers.

"See that word bolded there? That would leave open the possibility that there are more deceptions today, at least in terms of absolute numbers."

See that word bolded there? It leaves open the possibility that there are fewer deceptions today.

... which supports the idea that regulating or worrying about this shit doesn't matter any more than it used to.

" worrying about this shit doesn't matter any more than it used to."

What with the whole internet thing and globalization and stuff the stakes are higher than they used to be. Making decisions based on false information can lead to disastrous results.

The claim that people are less deceitful than our ancestors is actually a claim people do make, based on the fact that good trade requires honesty and forthrightness. Thousands of years so it didn't matter to be honest but fast forward to the classical era and large societies and suddenly people had to be honest in order to compete.

"Thousands of years so it didn't matter to be honest "

I have little choice but to take your word for it.

Someone get this dumbass a fidget spinner, quick.

Great article. Radiolab did a segment on this last year. Makes me wonder why we didn't see more faked/fraud photography in all sorts of contexts. Because that's a heck of a lot easier to pull off than videos. (Unless of course it is happening and everything is fake in which case haha very funny.)

The moon landing was faked in a a Hollywood studio. You can find the proof at...ack...

One word: Squatch.

SORRY, TONY, STEVE SMITH JUST NOT THAT INTO YOU.

Before the twentieth century of so there weren't videos or photos of any kind. That's the worst case scenario here, so I'm not really too worried.

One of those Whole Earth Review articles was "Clubbing seal pups - the other side of the story."

All about the dark world of discotheques where one can dance with underage seals.