Kentucky Teacher Protests Are Political Theater Without Substance

Teachers have shut down schools across the state, allegedly to protest pension changes. But those pension reforms are pretty mild.

About 5,000 teachers rallied at the Kentucky State Capitol on Monday to protest the passage last week of a pension reform measure that…well, it doesn't actually do much of anything to change their retirement plans.

But the bill might help bring Kentucky's public sector retirement plans back from the brink of financial collapse.

Under the terms of the bill that zipped through the legislature on Thursday, teachers hired after January 1, 2019, would be moved into a new retirement system using a so-called "hybrid cash-balance retirement plan," which retains some elements of a traditional pension and includes individual investment options similar to a 401(k) plan. Future hires know they won't lose their money—which makes the plans significantly less risky than 401(k) plans in the private sector—but taxpayers will no longer be responsible for making up the difference when the pension investments fall short of expectations. (The Pension Integrity Project at the Reason Foundation, which publishes this blog, provided technical assistance to Gov. Matt Bevin and state legislators as they crafted various pension reform proposals over the past year.)

Those future hires might also have to work a little longer before qualifying for retirement. While current teachers will still be able to retire after 27 years on the job, those hired next year will have to work until they are 65 or until their age and years of service add up to 87—a 57-year-old teacher with 30 years of service would be eligible to retire, for example.

None of those provisions affect the thousands of current and retired teachers who swarmed the state capitol promising to throw out the bums who had allegedly shortchanged their retirement plans. Andrew Beaver, a 32-year-old middle school math teacher, told The New York Times that he and his colleagues were angry about (in the Times' words) "not having a seat at the negotiation table" with Republican Gov. Matt Bevin and the Republican-controlled state legislature.

Bevin had pushed for a version of the bill that included changes to future cost-of-living adjustments for current teachers and retirees. But that provision was stripped from the bill after earlier opposition from the teachers who now say they did not have a seat at the negotiating table. Indeed, hundreds of teachers swarmed the state capitol in mid-March to have their voices heard as state lawmakers debated the pension proposal. The state set up a website to collect feedback from the public on various pension proposals too.

The public has the right to participate in the legislative process, but no one is entitled to get what they want out of it. This is political theater.

Protests like the one staged in Frankfort—and the walkouts in schools around the state this week—are meant to flex the public sector unions' muscles and make state lawmakers think twice about making more changes in the future. This isn't about retirement planning; it's about political power.

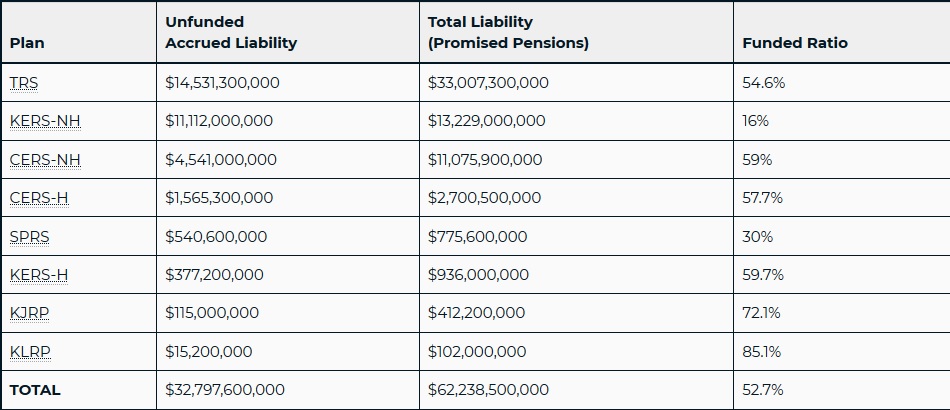

If it was about retirement planning, the teachers would admit that something has to change. Kentucky has eight public sector pension plans, and none of them are in good shape. The state faces more than $62 billion in unfunded pension liabilities over the next few decades, and the teachers' pension plan (the Kentucky Teachers Retirement System, or TRS) accounts for more than $33 billion of that debt.

By comparison, Kentucky taxpayers' paid about $32 billion last year to fund the entire state government—everything from schools to road construction.

Depending on how you measure, Kentucky's public sector pension plans are either the worst-funded or the third worst-funded in the country. A Standard & Poor's report in 2016 ranked Kentucky dead last, with just 37.2 percent of the assets needed to cover current obligations, behind even such infamous pension basket cases as New Jersey (37.8 percent) and Illinois (40.2 percent). A Moody's report published a month later measured states' pension liabilities as a percentage of their annual tax revenue. Kentucky's liabilities totalled 261 percent of annual tax revenue, well above the average burden of 108 percent and more than three times the median of 85 percent. Only Illinois and Connecticut were in worse shape.

There's no doubt that Kentucky's pension crisis is partially a self-inflicted wound caused by years of deferring contributions to the system. According to an analysis from the Pew Charitable Trusts, only 15 states contributed sufficient funds to their pension systems in 2014 (the most recent year for which complete data is available) to avoid falling farther behind. Among the 35 states that failed to do so, Kentucky was by far the biggest deadbeat, chipping in less than 70 percent of what is required. In the decade between 2006 and 2016, the Kentucky teachers' pension plan had negative cash flow in nine years, and hemorrhaged $634 million in 2016 alone.

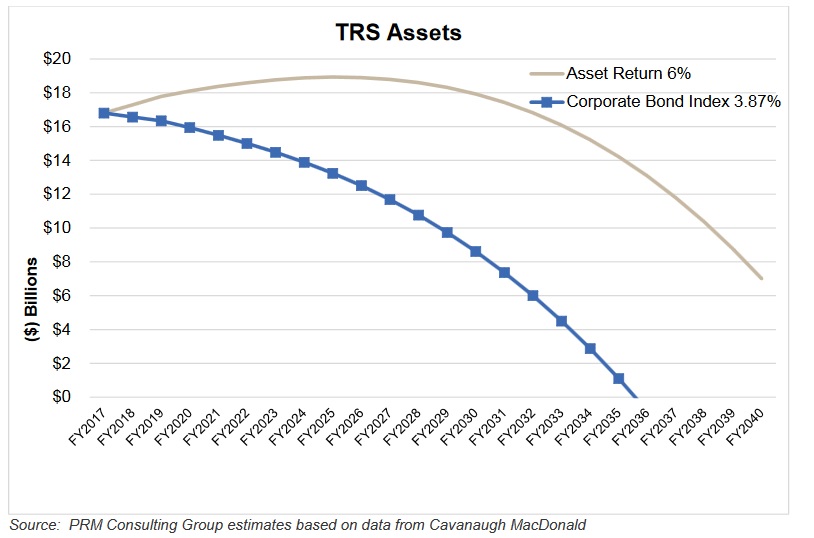

This is a completely unsustainable course. Any teachers just starting their careers in Kentucky's public schools should take a look at the chart below and ask if they're willing to trust their retirement to a system that could be insolvent by the mid-2030s if it earns less than 4 percent annually:

"The reaction to this common sense bill makes it clear that many educators had no intention of supporting any changes whatsoever to the pension system," writes Gary Houchens, a professor of education at Western Kentucky University. "Which also means that there was no need for further discussion on the topic in the state legislature. You're either going to stop kicking the can and do something, or you're going to let a broken system continue to spiral out of control."

The pension reform package that passed the state legislature last week won't solve that existing pension crisis. The current debt will still have to be paid, and it will continue costing Kentuckians for years to come. But the changes to pension promises for future teachers will allow the state to pay off the current debt without risking futher financial disaster.

Last month, Bevin said teachers were being "selfish and short-sighted" by opposing pension reforms. He's as right today as he was then.

Show Comments (121)