Happy 20th Birthday to Viagra, the Accidental Boner Pill That Changed America

Bob Dole's magical pill changed the way Americans think about sickness and treatment.

Twenty years ago today, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved orally administered sildenafil citrate tablets for the treatment of erectile dysfunction in the U.S., under the brand name Viagra.

The little blue pill, the most popular use of which was discovered by accident, helped change how prescription drugs are marketed, and shifted public perceptions of what drugs can and should do.

It was also an instant hit. Within two months of going to market, "approximately one million prescriptions had been written in the U.S. alone," according to a 2005 paper in the International Journal of Clinical Practice.

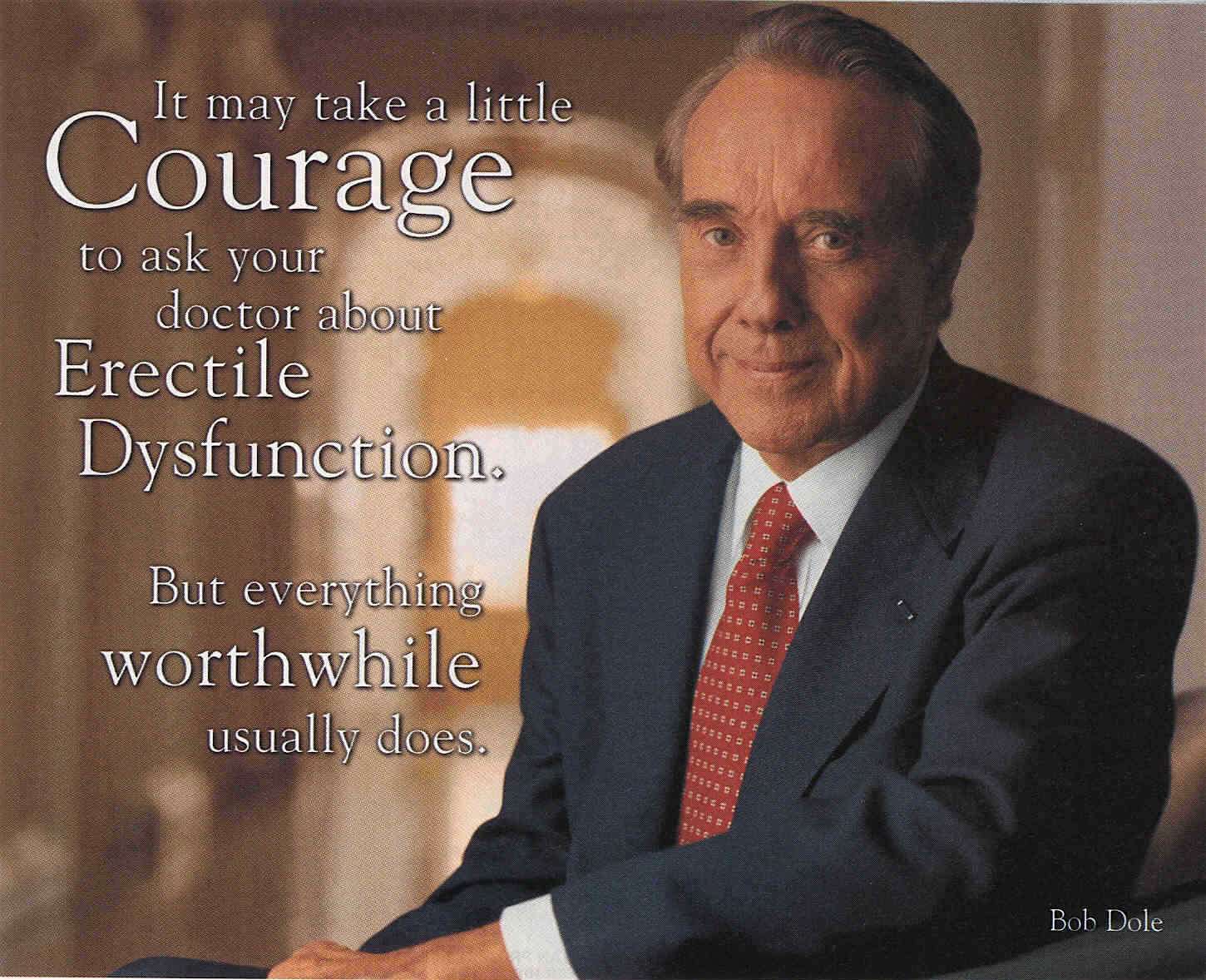

But Pfizer Inc., the company behind the drug, had bigger ambitions for Viagra, which was the first treatment of its kind for erectile dysfunction. The company wanted to hit $1 billion in sales during its first year of availability, but was on track for only $800 million by December of 1998. To close the gap, Pfizer hired one-time GOP presidential candidate and former Sen. Bob Dole (R-Kans.) to serve as pitchman for the drug.

Dole, then 75, was perfect for the role. A social conservative from the midwest who'd served in World War II, Dole acknowledged in May of 1998 that he'd participated in Viagra's clinical trial to treat the "impotence" he experienced as a result of undergoing surgery for prostate cancer in the early 1990s.

"It is a great drug. I'll be honest. I was in the protocol and participated in the program," Dole said during a live appearance on CNN's Larry King Live. "There are many men out there, millions of men out there, who suffer from impotence, and this may be the first step."

Various stories provide different explanations for how Pfizer learned sildenafil citrate worked better in the male member than the heart. In 2008, NPR told this story:

Pfizer was testing it as a cardiovascular drug for its ability to lower blood pressure, but it raised something else, earning it the nickname "the Pfizer Riser." So how did the researchers find out? Well, the apocryphal story goes, you can take this or leave it, the trial subjects who took the drug for its original purpose, they wouldn't give back the samples.

Last year, Quartz unearthed this story:

All seemed to be going well—except for one weird thing the men enrolled in the study did when nurses went to check on them. "They found a lot of the men were lying on their stomachs," John LaMattina, who was the head of research and development at Pfizer while this research was ongoing, said on a 2016 episode of the STAT Signal Podcast. "A very observant nurse reported this, saying the men were embarrassed [because] they were getting erections." It appeared that the blood vessels dilating were not in the heart, but rather the penis.

When Viagra went generic last year, Bloomberg's Joe Nocera noted its cultural impact thusly:

Viagra was the first drug to allow impotent men to maintain erections. That made it the first true "lifestyle" drug and showed the pharmaceutical industry that there was money to be made developing drugs that improved people's lives without curing disease or alleviating pain.

If creating a lifestyle drug was the first innovation, selling one was the second. Traditionally, companies sold drugs by having salespeople persuade doctors to prescribe them. But that wouldn't work for Viagra; doctors were as reluctant to ask patients about their sex lives as anyone else. The only way doctors were going to prescribe Viagra in large quantities was if patients asked for it.

Dole's ads became a "textbook case in condition branding," Colgate University's Meika Loe told NPR in 2008. That model—in which direct-to-consumer ads "educate" patients about the symptoms of a disease they often didn't know existed as part of promoting a branded treatment—is now the lifeblood of the drug industry.

It's probably one of the biggest reasons why prescription drugs that both work and feel good—narcotic sleep aids for insomnia, benzodiazepines for anxiety, amphetamines for ADHD, and testosterone for "Low-T"—saw their prescription rates increase dramatically over the last two decades, in lockstep with diagnoses of the associated conditions. Patients recognized some of their (ambiguous and/or common) "symptoms" in advertising, and knew exactly what to ask their doctor for when they went in to talk about it. Condition branding has also been used to "create" new diseases in order to find a use for compounds that don't otherwise have an obvious application.

Is condition branding bad? Did Pfizer and Dole open Pandora's Box? Many policy wonks have come to see the pharmaceutical information ecosystem as toxic, thanks in no small part to the role of physician-targeted marketing in the opioid crisis. But I'm skeptical that ads play the same role today, or that they are more bad than good. Between online social networks and drug and disease forums, pharmaceutical ads don't have near the informational monopoly they once did. It's also easier than ever before to check what a pitchman tells you against the available scientific evidence.

I also think we are bad at acknowledging the impact of things we cannot measure. When it comes to drugs, we can measure how much they cost and the rates of consumption, hospitalization, and death. We are less good at—and perhaps less interested in—measuring how drugs improve people's lives.

Regardless, Dole talking about his erectile dysfunction helped shift the Overton Window. He made it easier for American men to both accept that they were experiencing a problem they could not think their way out of and to seek an effective remedy. Yes, the success of Viagra helped drug companies develop a wildly profitable new advertising model. But I don't see that as a net negative if it paved the way for a social ecosystem in which more people talk about, and get help for, ailments like depression, anxiety, acne, and obesity; in which we feel free to talk openly with each other and our care providers about things like family planning and oft-embarrassing autoimmune disorders like IBD and plaque psoriasis.

As with every other aspect of modern life, the prescription drug landscape is not perfectly unproblematic. But as Viagra proved 20 years ago, "right now" is always the best time in history to have a medical problem.

Show Comments (79)