Arthur Miller's Daughter Humanizes Playwright in New Documentary

Some controversial behavior connected to the Communist Party gets played down.

Arthur Miller: Writer. HBO. Monday, March 19, 8 p.m.

The public image of the playwright Arthur Miller has always been chilly and cerebral, perhaps best summed up in his explanation to a reporter of why he wouldn't be attending the funeral of his ex-wife Marilyn Monroe, who committed suicide 18 months after they split: "She won't be there."

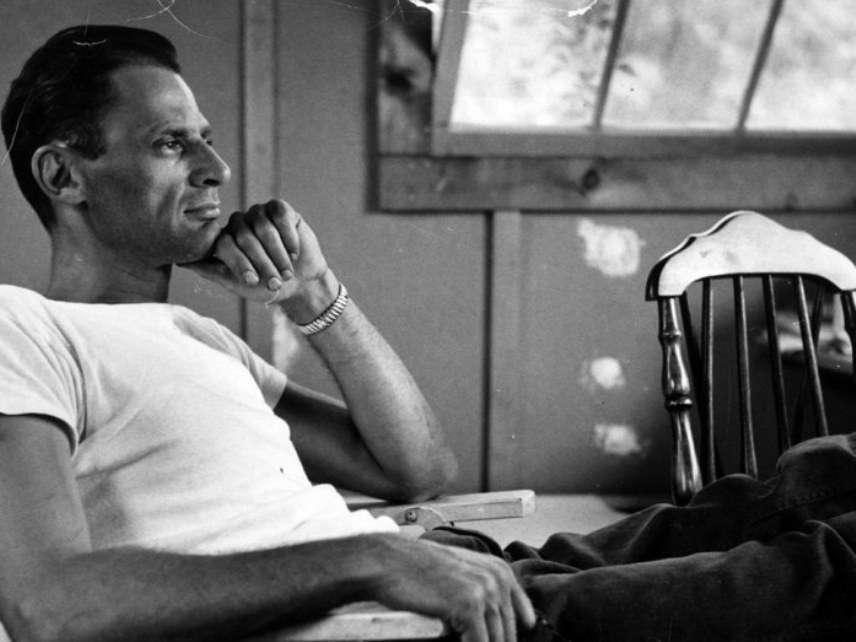

The signal achievement of Arthur Miller: Writer, a documentary made by his writer-filmmaker daughter Rebecca, is to introduce some color into that black-and-white picture. In old home movies and impromptu interviews shot over she shot over two decades, her father is seen joking, singing, building furniture (complete with the requisite cursing: "Goddamn angles drive you crazy," he mutters when pieces don't fit together), and swapping family folktales with his brothers and sisters.

Even his brief reminiscences about the stormy marriage to Monroe, though they sound cold (he couldn't do any writing during the marriage because "I guess, to put it frankly, I was taking care of her," which was "the most thankless job you can possibly imagine"), are spoken with an obvious pain that belies the wintry words.

Humanizing her father is at once the most singularly successful element of Rebecca Miller's documentary, and the source of its failures. "He lived through so many different eras, almost like different lifetimes," she says early during her narration of the documentary, an insightful observation.

There is Miller the star playwright, rattling Broadway with go-for-the-throat accounts of the crumbling dynamics of families whose patriarchs have been undone by outside forces: the delusional, failed Willie Loman of Death of a Salesman, or the sexually obsessed longshoreman Eddie Carbone of A View from the Bridge.

Then there's Miller the brave (and a bit preening) moralist of the Red Scares in the 1950s, projecting a carefully constructed image of an innocent and courageous writer being persecuted for showing character at a time when, in the words of his daughter, "it was dangerous to be a liberal and an artist."

There's also Miller the unwilling prey of the tabloids during the marriage to Monroe. Or Miller the gentle husband and dad, who when an adolescent Rebecca asked for a stereo, built one from scratch using discarded stuff he found at the dump.

The Miller Rebecca knew best was the affectionate dad, finally getting domesticity and parenthood right, mostly, when his best work was well behind him, and the sections of Writer devoted to him ring mostly warm and true. They also have a revelatory feel that's mostly not present the rest of the time; so much has been written about Miller's work and his public persona that there's probably little new left to tell. (Indeed, a number of soundbites that seem to come from Rebecca's interviews with her father are actually him reading from Timebend, Miller's 1987 autobiography.)

When Writer veers into other areas, it is not always as forthcoming. The account of Miller's marriage to Monroe concentrates entirely on her downward swirl of barbiturates and booze and doesn't mention that at least a small part of it probably resulted from her reading in his diary that he considered her an embarrassment around his friends. (Give Rebecca credit, though, for recounting the critical outrage at the vindictive and wildly egocentric play After the Fall, written by Miller after Monroe's death. The Village Voice suggested it be retitled I Slept with Marilyn Monroe.)

Much worse is her fractured retelling of the events surrounding Miller's confrontation with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and its investigation of Hollywood's Communist Party in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Director Elia Kazan, Miller's best friend and stage collaborator, was an embittered ex-Communist who agreed to testify and name names of other party members. ("I hate the Communists and have for many years, and don't feel right about giving up my career to defend them," Kazan said.) Miller didn't speak to him for 10 years, and also wrote a play, The Crucible, comparing HUAC and its witnesses as murderous witchhunters.

Eventually, Miller, too, got a subpoena. He denied ever being a Communist, even when HUAC confronted him with his written application for party membership. The manifest absurdity of his denial would be reinforced decades later when historians discovered Miller had been a secret writer for the Stalinist party cultural organ New Masses.

Nothing in Writer hints at Miller's underground life, his false testimony to HUAC, or his secret allegiance to the most murderous dictator of the 20th century. Even making allowances for a daughter's desire to put her father in the best possible light, that's a little much. Perhaps HBO can append an afterword when Writer is telecast. It doesn't have to be long; just a brief clip from On the Waterfront, Kazan's cinematic parting shot at Miller and the rest of the Hollywood Communists—the one where Marlon Brando, who plays a defector who testifies against the Mob, confronts his old friends. "I'm glad what I done to you, ya hear that?" he shouts. "I'm glad what I done!"

Show Comments (18)