Trump Orders Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum. Can Congress Stop Him?

A 25 percent tariff on steel and a 10 percent tariff on aluminum will take effect in 15 days, unless GOP lawmakers take unusual steps to stop them.

Well before he was president, Donald Trump wanted tariffs.

In an April 2011 interview with The Wall Street Journal, Trump said that if he were president, he would impose a 25 percent tariff on all Chinese goods imported into the United States. "Protectionism?" the future president scoffed when asked about the consequences of tariffs for the American economy. "I want to be protected."

Other aspects of his chaotic 2016 presidential campaign got more attention, but tariffs were always a part of the Trump platform. A tariff on Chinese goods would show that the United States was "not playing games anymore," Trump said at an August 2016 rally in Florida. Shortly after winning the election, Trump's transition team talked about the possibility of a 10 percent tariff on imports. And as his first year in the White House ticked along, Trump seemingly became more impatient. "I want tariffs," he reportedly bellowed during a tense discussion with some of his top economic advisers in August of last year.

On Thursday, Trump finally got his tariffs.

"We're going to be very fair, we're going to be very flexible, but we're going to protect the American worker, as I said I would do in my campaign," Trump said.

A 25 percent tariff on imported steel and a 10 percent tariff on imported aluminum will take effect in 15 days, the White House announced Thursday. Trump said he's willing to exempt Canada and Mexico from the tariffs, and to review other countries on a case-by-case basis. The tariffs would shelter domestic producers of steel and aluminum from some foreign competition, but at the expense of the many steel- and aluminum-consuming businesses in the United States. Consumers would end up paying more for everything from beer and baseball bats, to appliances and automobiles.

Republican leaders in Congress disagree with Trump's tariff plan, and publicly broke with the White House this week to denounce the tariff plans while simultaneously working behind the scenes to limit the scope of the new import taxes.

After Trump's announcement, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) released a statement warning of "unintended consequences" from Trump's trade action. Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) told Reason that he was opposing the tariffs in part because he was "very concerned about retaliatory action from other countries."

Words are one thing. But can Congress stop Trump's tariffs?

The answer is complex. Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the explicit power "to lay and collect taxes, duties," and the like. But Congress is limited in what it can do by law, and maybe more importantly, by politics.

First, the legal angle. Trump's tariffs are being implemented under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which gives the White House more or less carte blanche to impose tariffs on national security grounds. The national security rationale for tariffs on steel and aluminum is pretty weak—the administration says that American weapons of war depend on steel and aluminum supplies, so domestic producers must be protected from international supplies that could be cut-off in the event of a conflict—but it exists and that's enough.

"There's not much they can do to address this particular case," says Dan Ikenson, director of trade policy studies at the Cato Institute. "We're in uncharted waters in a lot of ways."

Handing over those powers to the executive branch might have been a prudent decision in some regards. Congress has, traditionally, been more open to protectionist policies like tariffs (just think about how defensive members of Congress get about anything in their home districts), while the presidency has been more likely to support free trade, in part because the executive branch handles international affairs and because the president gets credit (and blame) for the economy as a whole.

"They never anticipated having a protectionist president," says Ikenson.

But with Trump in the White House, the tariff fight has become another painful lesson about what happens when Congress abdicates its responsibility and hands power to the executive branch.

Last year, Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) introduced the Global Trade Accountability Act, which would require congressional approval of any unilateral trade action taken by the executive branch. Had it passed, Trump would have been required to outline the costs and benefits of his tariffs to Congress, instead of taking action on his own.

Trump's tariffs, Lee said Thursday, "would be a huge job-killing tax hike on American consumers." He urged Congress to take action to block them.

Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) is proposing to do exactly that. Shortly after Trump signed the tariff declaration on Thursday, Flake said he was prepping legislation to nullify the order.

"Trade wars are not won, they are only lost," said Flake. "Congress cannot be complicit as the administration courts economic disaster."

Congress has stepped in to stop executive action on trade deals before. In 1980, Congress overturned a Section 232 order from President Jimmy Carter that imposed an agricultural embargo on the Soviet Union. After Carter vetoed the bill, Congress (led by Democrats at the time) overrode him.

"Whether Congressional Republicans grow a spine is a big question," says Clark Packard, trade policy counsel for the R Street Institute, a free market think tank in Washington.

Even Flake seems to recognize the difficulty. He told The Daily Beast earlier this week that "trade votes are tough here." Getting to the 2/3 vote necessary to override Trump's inevitable veto would be harder still.

That's the political limitation on Congress' ability to check Trump. Will Democrats join Republicans in helping save the economy from a Republican president—while they are gearing up to campaign against that same Republican president in the midterms? Even discounting the Democrats' political incentives, there are good reasons to think Republicans won't go to the mat to challenge Trump on this—even if the tariffs trigger a trade war.

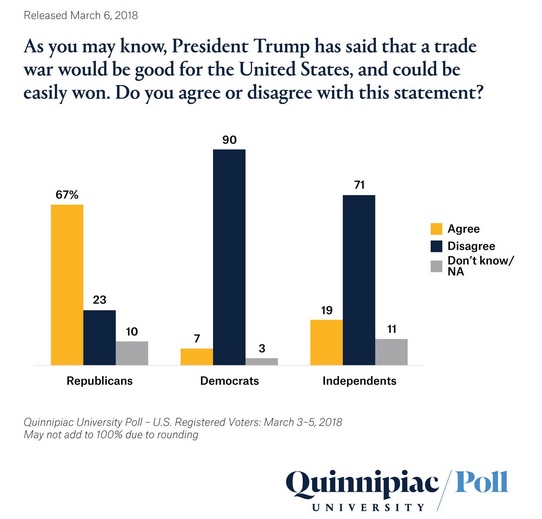

For example, there's a new Quinnipiac poll showing that 67 percent of registered Republicans believed Trump's claim that a trade war could be easily won. Democrats and independents strongly doubt that premise.

It's stunning to see such widespread support for protectionist economics—and wide support for a potentially destructive trade war—from members of the party that supposedly defends free trade, but if other polls show similar results, Republicans will have little reason to keep fighting the White House on this issue.

The best chance to stop Trump's tariffs was probably before Thursday. Now, Congress has a chance to act, but White House holds most of the power.

"I assumed that the president was rational and that he wouldn't want to kill his economy," says Ikenson. "It's a disaster."

Show Comments (130)