America's War on Pain Pills Is Killing Addicts and Leaving Patients in Agony

The government's efforts to get between people and the drugs they want have not prevented drug use, but they have made it more dangerous.

Craig, a middle-aged banking consultant who was on his school's lacrosse team in college and played professionally for half a dozen years after graduating, began developing back problems in his early 30s. "Degenerative disc disease runs in my family, and the constant pounding on AstroTurf probably did not help," he says. One day, he recalls, "I was lifting a railroad tie out of the ground with a pick ax, straddled it, and felt the pop. That was my first herniation."

After struggling with herniated discs and neuropathy, Craig consulted with "about 10 different surgeons" and decided to have his bottom three vertebrae fused. He continued to suffer from severe lower back pain, which he successfully treated for years with OxyContin, a timed-release version of the opioid analgesic oxycodone. He would take a 30-milligram OxyContin tablet twice a day, supplemented by immediate-release oxycodone for breakthrough pain when he needed it.

Then one day last May, Craig's pain clinic called him in for a pill count, a precaution designed to detect abuse of narcotics or diversion to nonpatients. The count was off by a week's worth of pills because Craig had just returned from a business trip and forgot that he had packed some medication in his briefcase. He tried to explain the discrepancy and offered to bring in the missing pills, to no avail. Because the pill count came up short, Craig's doctor would no longer prescribe opioids for him, and neither would any other pain specialist in town.

"I have lived my life by the rules," says Craig (whose name I've changed at his request). "I made one mistake, and they condemned me for it. They were basically saying that I'm a druggie when I have been fine for four years. My first pill count ever, and they boot me." He says a nurse at the practice told him "the doctors were getting tired of all the scrutiny, so they were booting all the opioid patients."

Without the OxyContin, Craig says, "every morning is a challenge to get out of bed." Even with liberal use of ice packs and Biofreeze, he says, "It's horrible. I can't expect to live a life like this. I'm not a junkie. I'm not a threat to society. I'm not a threat to myself. I simply want to live my life without pain."

Like other patients across the country, Craig is a victim of the recent crackdown on prescription opioids, which is based on a narrative that mistakenly blames pain treatment for a plague of addiction and death. Most Americans believe we are in the midst of an "opioid crisis" that began in the 1990s with the introduction of OxyContin. According to the generally accepted account, deceptive marketing encouraged reckless prescribing, which led to widespread addiction among patients and record numbers of opioid-related fatalities—a situation President Donald Trump has declared a public health emergency.

Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who chaired the President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, invokes that narrative when he talks about "the injured student-athlete who becomes addicted after [his] first prescription" or remembers the law school classmate who died of an overdose after getting hooked on the oxycodone he was taking for back pain. Such examples are misleading because they are rare, accounting for only a small percentage of opioid-related deaths.

Contrary to the impression left by most press coverage of the issue, opioid-related deaths do not usually involve drug-naive patients who accidentally get hooked while being treated for pain. Instead, they usually involve people with histories of substance abuse and psychological problems who use multiple drugs, not just opioids.

Conflating those two groups results in policies like the pill count that left Craig without the pain medication he needed to get out of bed in the morning, go to work, and lead a normal life. The rationale is that cutting people like him off will stop them from ending up dead of an overdose in a Walmart parking lot next to a baggie of fentanyl-laced heroin.

But the truth is that patients who take opioids for pain rarely become addicted. A 2018 study found that just 1 percent of people who took prescription pain medication following surgery showed signs of "opioid misuse," a broader category than addiction. Even when patients take opioids for chronic pain, only a small minority of them become addicted. The risk of fatal poisoning is even lower—on the order of two-hundredths of a percent annually, judging from a 2015 study.

Despite such reassuring numbers, the government is responding to the "opioid epidemic" as if opioid addiction were a disease caused by exposure to opioids, a simplistic view that ignores the personal, social, and economic factors that make these drugs attractive to some people. Treating pain medication as a disease vector, the government has restricted access to it by monitoring prescriptions, investigating doctors, and imposing new limits on how much can be prescribed, for how long, and under what circumstances. That approach hurts pain patients by depriving them of the analgesics they need to make their lives livable, and it hurts nonmedical users by driving them into a black market where the drugs are deadlier.

A large majority of opioid-related deaths now involve illicitly produced substances, primarily heroin and fentanyl. As usual, the government's efforts to get between people and the drugs they want have not prevented drug use, but they have made it more dangerous.

'Highly Addictive Drugs'

"We've known for millennia that opioids are highly addictive drugs," says Andrew Kolodny, executive director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing. "We have an epidemic of people with the disease of opioid addiction in the United States. The reason it's become an epidemic is because opioids have been overprescribed by my colleagues, who were led to believe that we didn't have to worry about addiction."

Kolodny, who is also co-director of opioid policy research at Brandeis University's Heller School for Social Policy and Management, says the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) started to "advocate for opioids" in the late 1990s, taking the position that "the risk of addiction has been overblown, even that the risk of overdose death has been overblown, and that we should be prescribing much more for people with chronic pain." As a result, he says, "we got our patients addicted, and we stocked people's medicine chests with addiction, so their kids wound up getting addicted."

This gloss is superficially plausible. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the amount of opioids prescribed in the United States more than quadrupled between 1999 and 2010, rising from 180 to 782 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per capita. During the same period, according to CDC data, the annual number of deaths involving the kinds of opioids prescribed for pain also roughly quadrupled, from about 4,300 to about 18,500.

The relationship is not quite as straightforward as it might seem. Opioid prescriptions, measured by MME per capita, fell by nearly a fifth from 2010 to 2015, while deaths involving these drugs continued to rise. The CDC's numbers also indicate that deaths involving opioid pharmaceuticals are not always more common in states with higher prescription rates. In 2015, for instance, West Virginia's death rate was more than twice as high as Tennessee's, although it had fewer opioid prescriptions per capita. Rhode Island, New Mexico, and Utah had higher death rates than Oklahoma, where opioids were prescribed substantially more often.

Still, the expansion of the legal market for opioids obviously had something to do with the increase in illegal use of these drugs. Many of the pills were diverted to nonmedical users, either after they were prescribed or through theft from points higher in the distribution chain.

But greater availability of prescription opioids cannot by itself explain the rise in addiction and drug-related deaths. "The question is why so many communities were so vulnerable to developing problems with opioids in the first place," says Daniel Raymond, policy director at the Harm Reduction Coalition. Part of the answer, he thinks, can be found in the same factors that helped elect Donald Trump. "These pockets of the Rust Belt and Appalachia, with the loss of manufacturing jobs or traditional industry jobs, were extremely primed for developing a drug problem," he says. "It happened to be opioids, but it could have just as easily been—and arguably it has also been—alcohol or methamphetamine."

When Kolodny says "we got our patients addicted," he discounts the way unhappy circumstances, such as unemployment and dim economic prospects, make drug use more appealing. He also implies that pain treatment has been the main route to opioid addiction during the last two decades. But that is not what the evidence indicates.

According to a 2014 analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 54 percent of nonmedical users got prescription opioids for free from friends or relatives. Another 16 percent bought or stole pills from friends or relatives, while 4 percent bought them from strangers. About 6 percent mentioned other sources, including online purchases, forged prescriptions, and theft from doctors' offices or pharmacies. Just 20 percent of nonmedical users said they obtained opioids through prescriptions written for them.

Although some people who now obtain opioids indirectly may have had prescriptions at some point, these results undercut the notion that nonmedical users typically start as bona fide patients. Even among the heaviest users, just 27 percent had prescriptions at the time of the survey, and it is not clear how many of those were legitimate at the outset. In most cases, says Sidney Schnoll, a physician specializing in addiction and pain treatment who works for the consulting firm Pinney Associates, "These are people who were drug-seeking. They are not people who went to a physician, got a prescription, and suddenly became addicted to the drug."

Stefan Kertesz, a University of Alabama at Birmingham internist who, like Schnoll, specializes in pain and addiction, agrees that the prevalence of iatrogenic opioid addiction (that is, addiction resulting from medical treatment) has been exaggerated. "I think a meaningful percentage did start in care of pain," he says, "but everything I've read leaves me with the sense that the overwhelming majority of the people who are dying of overdose began with diverted pills."

The NSDUH data reinforce the impression that doctors frequently prescribe more pain pills than their patients end up needing. People who take opioids after an injury or surgery might receive enough pills for two weeks but use only half of them. It seems likely that diverted opioids more often come from such short-term prescriptions than from medication prescribed for people suffering from severe chronic pain, who probably are not keen to share or sell the drugs that keep their agony at bay.

The fact that people frequently have leftover opioids that they give away, sell, or leave in their medicine cabinets to be swiped suggests these drugs are not quite as irresistible as they are reputed to be. According to NSDUH, 98 million Americans used prescription analgesics in 2015, legally and illegally. Judging from their responses to survey questions, about 2 million of them—slightly more than 2 percent—qualified for a diagnosis of "substance use disorder" (SUD) at some point during the previous year.

SUD is a catchall category that subsumes what used to be known as "substance abuse" and the more severe "substance dependence." The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which oversees NSDUH, does not report the breakdown between mild, moderate, and severe SUDs. But based on this survey, it looks like somewhere between 1 percent and 2 percent of prescription opioid users experience addiction in a given year. By comparison, NSDUH data indicate that 9 percent of past-year drinkers had an alcohol use disorder in 2015. That group was about evenly divided between "abuse" and "dependence."

'Narcotics Are Not That Appealing'

Stanton Peele, a psychologist and addiction expert, observes that, contrary to conventional wisdom, "narcotics are not that appealing" to most people. In addition to the NSDUH data, he cites research finding that hospital patients who are allowed to self-administer pain medication tend to take less than those who get it on a fixed schedule. "On their own," he says, "people only use it when they're in pain."

The notion that opioid addiction is "an equal-opportunity destroyer," as politicians and drug treatment boosters like to say—or that "everyone is at risk and every family prey to loss," as Mitchell Rosenthal, founder of the Phoenix House treatment centers, told the Christie commission—is "absolutely false," Peele says. To the contrary, opioid addiction is strongly associated with unemployment, poverty, family dysfunction, and pre-existing psychological issues. Well-adjusted people with supportive families, strong social ties, and good economic prospects are much less likely to seek refuge in opioids than people who lack those advantages. To put it another way, mere exposure to opioids does not produce addiction. A drug will become the focus of a tenacious habit only if it serves an important function in the user's life.

"I didn't realize how much I was trying to run away from myself," says Jill, a former heroin user from Ohio who has been anxious since childhood, received a diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder as an adult, and was a victim of sexual assault in college. "I wasn't really cognizant of how difficult it was to be in my own head. I'd had a lot of trauma that I wasn't dealing with, and everything was piling up. The appeal of heroin was it turned everything off. It was like a vacation." In rehab, Jill realized that other opioid users had similar issues. "They either have a trauma or a mental illness that they're trying to deal with," she says, "and nobody gave them the tools to do that."

Kolodny concedes that most people who use opioids do not develop an addiction. "You don't become addicted by using a highly addictive drug once or twice," he says. "You can use a highly addictive drug on an intermittent basis and not get addicted. It's repeated use that puts people at very high risk of becoming addicted."

But even in studies of patients who take pain medication repeatedly and regularly, sometimes for months or years, the addiction rates are generally modest. As Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and A. Thomas McLellan, a former deputy director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, noted in a 2016 New England Journal of Medicine article, "Addiction occurs in only a small percentage of persons who are exposed to opioids—even among those with preexisting vulnerabilities."

A 2010 analysis in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews found that less than 1 percent of patients taking opioids for chronic pain experienced addiction. A 2012 review in the journal Addiction likewise concluded that "opioid analgesics for chronic pain conditions are not associated with a major risk for developing dependence."

A study reported in The BMJ this year tracked 568,612 opioid-naive patients who took prescription pain medication following surgery and found that 5,906, or 1 percent, showed signs of "opioid misuse" during the course of the study, which included data from 2008 through 2016. Although some studies have described "rates of misuse, abuse, and addiction-related aberrant behaviors" as high as 26 percent among chronic pain patients, Volkow and McLellan reported, "rates of carefully diagnosed addiction" average less than 8 percent.

Fatal overdoses among patients are even rarer. A 2015 study reported in the journal PLOS One followed chronic pain patients treated with narcotics for up to 13 years and found that one in 550 died from an opioid-related overdose, which is a risk of less than 0.2 percent over the course of the study. A 2015 study of opioid-related deaths in North Carolina, reported in Pain Medicine, found 478 fatalities among 2.2 million residents who were prescribed opioids in 2010, an annual rate of 0.022 percent.

Kolodny cites a 2012 study of deaths involving prescription opioids in Utah, reported in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, to support his contention that iatrogenic addiction accounts for "the bulk of the overdose deaths." In 87 percent of the cases, relatives or other people who knew the decedents said they had received prescriptions for pain medication in the previous year.

Other studies, however, indicate that prescribed drugs play a smaller role in opioid-related fatalities than that number suggests. In the North Carolina study, only half of the decedents had active prescriptions for opioids when they died. A 2008 study of West Virginia deaths involving opioid analgesics, reported in the American Medical Association journal JAMA, found that most of the decedents had never been prescribed opioids. A 2012 study of opioid users in Maine, reported in Addictive Behaviors, found that two-fifths reported chronic pain, but more than three-quarters of those subjects said their opioid use preceded their symptoms. A 2014 study of people who were treated in emergency rooms for overdoses involving prescription opioids, reported in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that just 13 percent had a chronic pain diagnosis.

Even when someone who dies from drug poisoning has an opioid prescription, it does not necessarily mean he was a bona fide patient. Patients can fool doctors, and some doctors are eager to be fooled. "Pill mill" cases in Florida and West Virginia have involved doctors who saw as many as 70 patients a day, each of whom paid $100 to $300 in cash, and doctors who wrote prescriptions without meeting patients or looking at their files. Such examples do not tell us much, if anything, about legitimate patients who become addicted while being treated for pain.

"These pockets of the Rust Belt and Appalachia, with the loss of…traditional industry jobs, were extremely primed for developing a drug problem."

Whatever share of people who die from drug poisoning began using opioids as legitimate patients, the share of patients taking opioids who die from drug poisoning is tiny—and the risk is not random. In the Utah study cited by Kolodny, 61 percent of the decedents had used illegal drugs, 80 percent had been hospitalized for substance abuse (including abuse of alcohol and illegal drugs as well as prescription medications), 56 percent had a history of mental illness, and 45 percent had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons other than substance abuse.

NSDUH data indicate that most nonmedical users of prescription opioids use other drugs as well, a fact that is reflected in mortality data. In the West Virginia study, 79 percent of the deaths involved combinations of drugs. In North Carolina, benzodiazepines such as Valium and Xanax were detected in 61 percent of the people whose deaths were attributed to prescription opioids, and that's just one class of depressants. In New York City, which has one of the country's most thorough systems for recording causes of death, 97 percent of drug-related deaths involve more than one substance. A 2003 study of 919 deaths attributed to oxycodone, reported in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology, likewise found that 97 percent involved combinations of drugs.

It seems clear that people by and large are not dying simply by taking too many pain pills. Even Chris Christie's law-school friend washed down his Percocet with vodka.

What's true of prescription analgesics is also true of illegal opioids. So-called overdose deaths generally involve mixtures of drugs, as reflected in the toxicology results for celebrities such as John Belushi (heroin and cocaine), River Phoenix (heroin, cocaine, and diazepam), Chris Farley (heroin and cocaine), Cory Monteith (heroin and alcohol), and Philip Seymour Hoffman (heroin, cocaine, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines). It is misleading to call such deaths "overdoses" (as opposed to, say, "mixed drug intoxication," the phrase used by the medical examiner who handled Hoffman's case), since people who die after taking an opioid along with other substances might still be alive if they had taken the opioid by itself.

Heroin Gets Deadlier

As these examples suggest, attributing deaths to particular drugs can be tricky, especially since methods for making that determination vary widely from one jurisdiction to another. But one thing is clear: Prescription analgesics are no longer the main factor in opioid-related deaths. In 2013 and 2014, according to an analysis by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 85 percent of opioid-related fatalities in that state involved heroin and/or fentanyl. A prescription analgesic was the deadliest drug in just 5 percent of the cases.

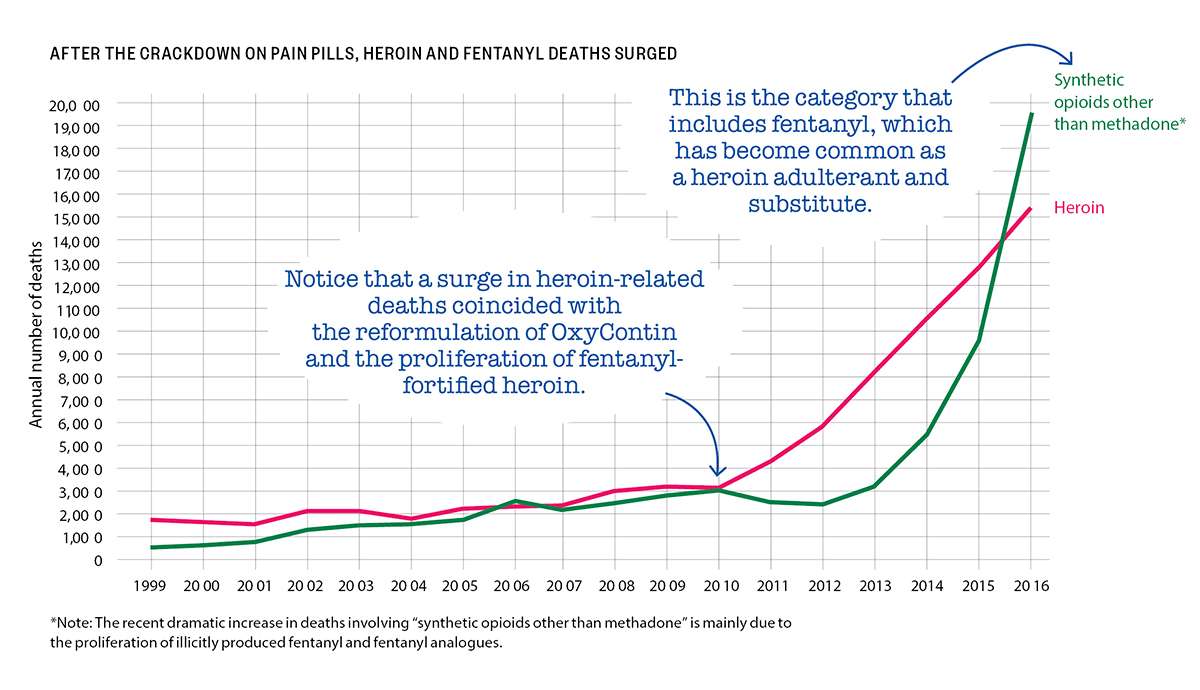

National data show a similar pattern. The CDC says there were more than 42,000 opioid-related deaths in 2016, including about 15,500 deaths involving heroin. About 19,400 deaths involved "synthetic opioids other than methadone," a category that consists mainly of fentanyl and its analogues, which nowadays are generally manufactured by drug traffickers rather than pharmaceutical companies. Prescription analgesics were implicated in about 17,900 drug poisoning fatalities.

Since some deaths involve more than one opioid, the total is smaller than the sum of the subcategories. But the CDC's numbers indicate that just two-fifths of opioid-related deaths in 2016 involved prescription analgesics, and some of those deaths also involved heroin, fentanyl, or its analogues.

Fentanyl is roughly 40 times as potent as heroin, which helps explain its appeal to drug dealers, who can use it to smuggle more doses in the same volume and to boost the impact of heroin that has been diluted by cutting agents. The increased use of fentanyl makes the potency of black-market heroin, which was always unpredictable, even more variable, raising the risk of fatal drug poisoning.

Indeed, heroin-related deaths, which began rising gradually in 2005, quintupled between 2010 and 2016. Deaths involving the category of opioids that includes fentanyl more than tripled between 2010 and 2015, then doubled in 2016 alone.

During the same period when heroin-related deaths rose by 400 percent, the number of heroin users counted by NSDUH rose by just 53 percent. NSDUH probably misses a lot of heroin users, both because respondents are especially reluctant to admit using that drug and because the survey sample does not include people who are institutionalized or have no fixed residence. But the NSDUH data still should give us a pretty good sense of how much the group of heroin users has expanded, if not its absolute size. And those data indicate that the number of heroin deaths has increased roughly eight times as fast as the number of heroin users.

To put it another way, heroin was eight times deadlier in 2016 than it was in 2010. The proliferation of fentanyl-fortified heroin is the most obvious explanation.

A research team headed by Brown University medical anthropologist Jennifer Carroll found that fear of fentanyl was common among the Rhode Island opioid users they interviewed for a study reported in The International Journal of Drug Policy last year. "Participants who were aware of fentanyl universally described it as dangerous and potentially deadly," Carroll and her colleagues write. "People are dropping like flies," one heroin user said. "I don't want to die," said another, explaining why he buys heroin only from a dealer he trusts not to sell him fentanyl-laced powder. Others said they try to avoid fentanyl and take "test hits"—small trial doses—whenever they suspect it is present.

Many of the people who are dealing with black-market powders of unknown composition were previously accustomed to the predictable doses of legally manufactured analgesics. "I used to take just the pills, and then I started doing dope, the heroin, only when I could get it, when it was cheaper," said a female opioid user quoted by Carroll and her collaborators. "But I don't prefer it because you never know what you're getting. It's scary, so I'm more into pills."

She was right to be scared. Comparing deaths counted by the CDC to users counted by NSDUH indicates that heroin is more than 10 times as lethal as prescription opioids. Even if that calculation exaggerates the difference because NSDUH undercounts heroin users, it seems clear that switching from prescription opioids to black-market substitutes dramatically increases the risks that users face.

Despite the dangers, that sort of switch is much more common today than it used to be. A 2014 study of heroin users entering treatment, reported in JAMA Psychiatry, found that 80 percent of those who began using opioids in the 1960s started with heroin. By contrast, Washington University neuropharmacologist Theodore Cicero and three other researchers noted, 75 percent of those whose opioid abuse began in the 2000s "reported that their first regular opioid was a prescription drug." (That does not necessarily mean it was prescribed for them.)

A more recent study led by Cicero, reported last year in the journal Addictive Behaviors, suggests that trend has reversed. Cicero and his co-authors report that a 2015 survey of people entering treatment for opioid use disorder found 33 percent had started with heroin, up from 9 percent in 2005. That finding is consistent with the hypothesis that troubled people who find emotional relief in drugs will turn to whatever options are most readily available. During the period when Cicero found that more and more opioid users were starting with heroin, pain pills were becoming harder to obtain thanks to surveillance, tighter regulations, and investigations of doctors.

"As the most commonly prescribed opioids—hydrocodone and oxycodone—became less accessible due to supply-side interventions, the use of heroin as an initiating opioid has grown at an alarming rate," Cicero and his co-authors conclude. "Given that opioid novices have limited tolerance to opioids," they add, the variability in potency typical of the black market poses a special risk to them, which is "likely to be an important factor contributing to the growth in heroin-related overdose fatalities in recent years."

'You Have to Start Somewhere'

To the extent that the crackdown on prescription analgesics has made them more expensive and harder to get, it has pushed opioid users toward more dangerous drugs. That helps explain why total opioid-related fatalities more than tripled from 2002 to 2016, even as illegal use of pain pills declined.

"We're funneling them from those drugs that were FDA-approved, you know what the dose was, they were predictable, towards drugs that are less predictable and more likely to cause overdose," says Daniel Raymond, whose work at the Harm Reduction Coalition involves finding ways to make drug use less lethal. With legally produced opioids, he says, "I have this zone that I stay in, and that's anchored by the fact that I know exactly what dose is in each pill. If I'm buying heroin every day…I never know the relative potency and concentration that I'm getting. I might be going to different dealers, and one week there's fentanyl in my heroin, and the next week there's not. I cannot self-titrate. I cannot optimize my dosing to stay within that window where I'm not going through withdrawal but I'm not at risk of overdose."

In a 2017 interview with the Carlisle Sentinel, Carrie DeLone, Pennsylvania's former physician general, confessed that "we knew that this was going to be an issue, that we were going to push addicts in a direction that was going to be more deadly." Her justification: "You have to start somewhere."

For a sense of where that attitude can lead, consider what happened after the reformulation of OxyContin. Introduced in 1996, the drug was widely blamed for the subsequent rise in opioid-related deaths, even though most of those deaths actually involved short-acting pain pills.

In 2007, Purdue Pharma, the company that makes OxyContin, pleaded guilty to "misbranding" the product by minimizing its abuse potential. Three years later, the Food and Drug Administration approved a new, "abuse-deterrent" formulation of the drug, which was designed to make it harder to crush and snort or inject. When the reformulated OxyContin is mixed with water, it forms a gel.

The old version of OxyContin was withdrawn from the market when the new one was introduced, a switch that coincided with the post-2010 spike in heroin-related deaths. In a 2017 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Wharton School health economist Abby Alpert and two RAND Corp. researchers investigate whether those developments were related by comparing states with different pre-2010 rates of nonmedical OxyContin use.

"We estimate large differential increases in heroin deaths immediately after reformulation in states with the highest initial rates of OxyContin misuse," Alpert and her colleagues write. "Our results imply that a substantial share of the dramatic increase in heroin deaths since 2010"—perhaps as much as 80 percent—"can be attributed to the reformulation of OxyContin." They conclude that the increase in heroin-related fatalities offset any decrease in OxyContin-related fatalities, "leading to no net reduction in overall overdose deaths."

There is some evidence that prescription drug monitoring programs, which allow regulators and law enforcement agencies to track the controlled substances a doctor prescribes, also have led people to substitute illicitly produced drugs for pills. A 2017 study reported in The American Journal of Managed Care found that such programs, which by 2015 had been adopted by every state except Missouri, "were not associated with reductions in drug overdose mortality rates and may be related to increased mortality from illicit drugs and other, unspecified drugs."

Harm Maximization

Responding to the shift from prescription analgesics to heroin and fentanyl, drug warriors have further magnified the dangers opioid users face by cracking down on those markets. A heroin user who tries to avoid fentanyl by sticking with a dealer he deems trustworthy may face increased risks if that dealer is arrested. Similarly, the FBI may be endangering drug users when it shuts down websites that help reduce hazards to consumers by selling fentanyl-free heroin or offering opioids in uniform liquids that make dosing easier.

Arresting opioid users also increases the risk of a fatal drug reaction, since abstinence imposed by jail or mandatory treatment reduces their tolerance. Once they get out, the doses to which they were accustomed before they were arrested may prove lethal. "There's one study that shows that someone's risk of overdose in the two weeks following their release from incarceration is up to 25 times higher than it is normally," says Carroll, the Brown University medical anthropologist. "People are overdosing right after they get out of prison."

Another policy that almost seems designed to make fatal poisoning more common is charging people with homicide if someone dies after taking a drug they supplied. Because prompt medical attention is crucial in saving people from potentially lethal opioid reactions, 40 states and the District Columbia have enacted "911 Good Samaritan" laws that shield bystanders from certain drug-related charges when they call for help. But if those bystanders know they might be prosecuted for murder should rescue attempts fail, they will think twice before dialing 911.

According to a 2017 report from the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA), 20 states have laws that specifically address drug-induced homicide, while others "charge the offense of drug delivery resulting in death under various felony-murder, depraved heart, or involuntary or voluntary manslaughter laws." Potential prison sentences range from two years to life, which is the minimum penalty in six states; the death penalty is possible in Colorado and Florida. Under federal law, drug distribution resulting in death or serious injury is punishable by 20 years to life. These statutes have been on the books since the 1980s, but prosecutions seem to have risen sharply in recent years, judging from mentions in news stories, which by the DPA's count more than tripled between 2011 and 2016, from 363 to 1,178 per year.

Although politicians may claim that drug-induced homicide prosecutions are aimed at high-level dealers, the targets are usually people close to the decedents. Someone's role in "distributing" the drug may be limited to buying it for someone else or sharing a stash. Even when money changes hands, the dealers are often selling just enough to finance their own habits. Cases cited by the DPA include a small-time New Hampshire dealer who did not realize the heroin he sold a friend contained fentanyl but got 10 to 30 years anyway, an Ohio woman who got three years after she took heroin with her father and woke up to find him dead, and a Minnesota woman who got six years because her husband died after taking methadone prescribed for her, even though she called 911 and tried to save his life.

"The vast majority of charges," the DPA says, "are sought against those in the best positions to seek medical assistance for overdose victims—family, friends, acquaintances, and people who sell small amounts of drugs, often to support their own drug dependence." The report concludes that "the only behavior that is deterred by drug-induced homicide prosecutions is the seeking of life-saving medical assistance."

One widely endorsed policy that actually holds promise for reducing drug-related deaths is easier access to naloxone, a.k.a. Narcan, an overdose-reversing opioid antagonist that can be administered by injection or nasal spray. Dispensing naloxone along with pain medications, making it available without a prescription (which 41 states currently allow), supplying it to first responders, and distributing it to friends and relatives of opioid users are ways to increase the odds that it will be used promptly when someone needs it. Speed is especially important when a person overdoses on fentanyl, which can cause lethal respiratory depression faster than heroin.

"I have a four-milligram Narcan in my purse right now," says Jill, the former heroin user in Ohio, who adds that she has "Narcanned" friends "probably dozens" of times. "You hope you don't have to use it, but you might have to. Everyone should have one. That is the only way that I can see the epidemic being managed at all."

For some drug warriors, naloxone's lifesaving potential is a bug, not a feature. In 2016 Maine Gov. Paul LePage, a Republican, vetoed a bill allowing pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription. "Naloxone does not truly save lives; it merely extends them until the next overdose," he wrote in his veto letter. "Creating a situation where an addict has a heroin needle in one hand and a shot of naloxone in the other produces a sense of normalcy and security around heroin use that serves only to perpetuate the cycle of addiction."

LePage's argument is familiar from the debate over needle exchange programs: For the sake of deterrence, he thinks, drug use should be as dangerous as possible. Maine legislators, who overrode LePage's veto, apparently disagreed.

How to Not Die

Drug testing is another promising form of self-help. Test strips and reagent kits that cost a dollar or two each can tell opioid users if the powder they just bought contains fentanyl. Some tests also detect common fentanyl analogues. A recent pilot study in Vancouver found that 83 percent of drugs thought to be heroin tested positive for fentanyl. Drug users were 10 times as likely to take less than usual and 25 percent less likely to overdose if they tested their drugs before injecting.

"It becomes this concrete, physical manifestation that opens up a conversation about fentanyl risks," the Harm Reduction Coalition's Raymond says. "If we've got fentanyl in our community, whatever you've been doing to minimize or avoid overdose, you need to up your game because it might not be enough against fentanyl. If you're careful about how much you use, if you're careful about what dealers you buy from, you might need to start thinking about not using alone and making sure you've got extra naloxone on hand."

The fact that drug mixtures figure in the vast majority of deaths involving heroin and other opioids suggests that discouraging particularly dangerous combinations could save lives—assuming it actually has an impact on people's behavior. "I think there's a huge role for education around that," Carroll says, citing a spate of heroin-related deaths in the late 1990s among high school students in Plano, Texas, some of whom died after snorting the drug while drinking. "It was just a pure educational gap, because I don't think there was any reason to believe that anyone was being deliberately cavalier. Educating people about how to not die is always worth our time."

Jill, the former heroin user, is less sanguine. "You're telling somebody, 'Don't mix benzos with heroin because it potentiates the heroin,'" she says. "They will mix the benzos with the heroin because they want to potentiate the heroin. One of the earliest things I learned was that if you take benzos it'll make your high better."

Raymond agrees that people who like to mix drugs and have done it repeatedly without any close calls won't be very receptive to the message that they are being reckless. "What we want to address is the environment of risk," he says. "And we can do that by saying, 'Hey, make sure that you have naloxone available. Don't use alone.' We can do that by talking about things like supervised injection facilities."

Such facilities provide a safe environment where people can take drugs they bring with them under medical supervision and get help immediately if they need it. The facilities may also offer services such as drug testing, syringe exchange, and assistance finding treatment. Studies of Insite, a supervised injection facility that has been operating since 2003 in Vancouver, have found that it boosted treatment admissions and reduced public drug use, needle sharing, and opioid-related deaths without raising local crime rates.

As a risk reduction strategy, letting people inject drugs at a place like Insite represents a distinct improvement over having them do it in the restroom at the public library in the hope that if they overdose they'll be discovered before it's too late. The first government-sanctioned supervised injection facilities in the United States are expected to open this summer in San Francisco. Officials in Seattle and Philadelphia are also interested in the idea.

Raymond notes that naloxone and needle exchanges "have gained increasing acceptability and, to varying degrees, lost their aura of controversy." But now that policy makers are beginning to talk about allowing supervised injection facilities, he says, "it's almost like a flashback to the '90s," when opponents of syringe exchanges argued that they should not be allowed because they encourage drug use. "It forces people to confront the question of how we feel about people using drugs and what are we willing to do to save their lives," he says. "The fact that it's even on the table is a testament to how far we've come."

People by and large are not dying simply by taking too many pain pills. Even Chris Christie's classmate washed down his Percocet with vodka.

So-called medication-assisted treatment, which combines counseling and behavioral therapy with substitute opioids, is not as controversial as supervised injection facilities. Research indicates that methadone, which has been used as a treatment for heroin addiction since the 1960s, reduces treatment dropout rates, heroin use, drug-related fatalities, and criminal activity. Buprenorphine seems to be about as effective as methadone at keeping users in treatment, reducing heroin use, and preventing premature death. Methadone is very strictly regulated, available only at special clinics that enrollees must visit to consume their daily doses. Buprenorphine is more widely available, but caps on the number of people a doctor can treat and conditions for prescribing it, including at least eight hours of special training and a federal waiver, make it harder to get than it should be.

Methadone and buprenorphine are the only opioids that can legally be prescribed for addiction treatment or maintenance in the United States. A wider range of options, including analgesics such as hydromorphone (a.k.a. Dilaudid) or diacetylmorphine (a.k.a. pharmaceutical heroin), probably would make treatment more attractive and therefore more effective for a wider range of people. Heroin is banned for all uses in the United States, but heroin maintenance is legal in Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Studies show it is more effective than methadone at promoting retention, reducing illicit drug use, and improving health outcomes.

Heroin maintenance "can be effective for people who have not had success with something like methadone," Raymond says. Even for people who eventually end up on methadone, "it may be an intermediate step to transition people off of a street supply of heroin." That switch alone would improve the odds of survival, since the potency of legally produced opioids is consistent and predictable.

"It's not clear at all, when we review the data, that there's a painkiller epidemic or a heroin addiction epidemic," Peele, the psychologist, says. "There's a death epidemic, and the way to address that is to guarantee the best, most regular, and purest supplies of drugs." Schnoll, the pain and addiction specialist, agrees that "if people can get their drug at a reasonable cost, knowing the purity of it, being able to use it safely, people are going to migrate to that."

Punishing Patients

In contrast with these harm reduction tactics, continuing attempts to discourage the use of prescription pain medication promise to cause a lot of needless suffering without making a noticeable dent in opioid-related deaths. Prescription guidelines that the CDC issued in March 2016, which minimize the benefits of opioids, exaggerate their risks, and encourage doctors to be stingy with them, exemplify this misguided strategy.

A 2016 critique published by the journal Pain Practice challenges several key aspects of the CDC document, including its recommended dose ceilings, its general declaration that nonopioid treatment is "preferred for chronic pain," its suggestion that opioid prescriptions for acute pain last no longer than seven days, and its statement that doctors who decide to prescribe opioids should begin with immediate-release products rather than extended-release or long-acting (ER/LA) analgesics.

The criticism of that last recommendation sums up what is wrong with the guidelines in general. "It appears that this statement is asking physicians to make prescribing choices based on public health concerns…rather than the most appropriate course of therapy for the individual patient," write pain specialist Joseph Pergolizzi and the six other authors of the Pain Practice article. "If prescribers must forego the use of ER/LA opioids in patients who could possibly benefit from them, it essentially punishes the chronic pain patient for offenses committed by drug abusers."

The CDC guidelines in themselves are not legally binding. But Congress has imposed them on the Department of Veterans Affairs (V.A.), and at least 18 states have enacted elements of them. In 2016 and 2017, according to a tally by the National Conference of State Legislatures, 14 states imposed limits on the duration of initial prescriptions for acute pain, ranging from three days (Kentucky) to two weeks (Nevada), with seven days the most common. Arizona enacted a similar law in January. Four states (Arizona, Maine, Nevada, and Rhode Island) have imposed daily dose ceilings, while Maryland limited opioid prescriptions to "the lowest effective dose" and a quantity "not greater than needed for the expected duration of pain." The legislatures of seven other states directed or authorized other bodies to impose limits on opioid prescriptions.

In addition to these statutory changes, the CDC guidelines are shaping the policies and practices of regulators, insurers, and law enforcement agencies. Doctors face "pressure from many directions," the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Kertesz notes. That includes "scrutiny from state officials," "barriers from insurance and pharmacy benefit plans," "more restrictive guidelines from state licensing boards," "stories of some physicians losing their livelihoods and being shut down," and "super-intense rhetoric from thought leaders and journalists," who tend to blame physicians for causing the "opioid epidemic" through careless prescribing. "Under that kind of pressure," Kertesz says, "who wouldn't change what they're doing, even if it hurts a few patients?"

Some physicians have decided the safest course is to stop prescribing opioids altogether. "There are many pain clinics flooded with patients who have been treated previously by their primary care physician," says Jianguo Cheng, president-elect of the AAPM. These refugees include patients who "have been functional" and "responding well" to opioids for "many years."

Schnoll sees similar problems. "Pain is still undertreated, and unfortunately it's getting worse because of the backlash that's occurring," he says. "I still get calls from patients whom I treated years ago, who were on stable doses of medication, doing very well, who have chronic pain conditions, and they can't get medication to treat their pain. They're being taken off medication on which they had done very well for years."

One such patient, a former cable company salesman named John, successfully used OxyContin to treat the back pain caused by injuries sustained during a mugging in 2011. Before he found a medication that worked for him, he recalls, "my wife was about to leave me, because I was a miserable bastard. When you're in that much pain, you want to just go to sleep and not wake up."

After the CDC guidelines came out, John was told that his daily dosage had to be cut in half. "My whole life turned upside down in a matter of 30 days," he says. "I'm back in bed now. I can't really get up very much, and I'm right back where I started in 2011."

'Can't Take It Anymore'

Maxx Lamb, a Kansas college student, became a pain treatment activist as a result of his experience with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a hereditary connective tissue disorder. He sent me a photograph of a sign at a doctor's office in Washington state that reflects the impact of the CDC's guidelines. "Beginning February 2017," it says, "Morphine Equivalency Dosing WILL decrease until CDC guidelines are met by June 2017. Target is 90mg of Morphine equivalency per day, or less. All medication adjustments will be based on this new clinic policy."

The CDC guidelines do not explicitly say patients should never exceed 90 morphine milligram equivalents a day, but they do suggest that such doses are hard to defend. "Clinicians should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage," the CDC says, and "should carefully reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks when considering increasing dosage" to 50 MME per day or more. The guidance adds that doctors "should avoid increasing dosage" above 90 MME per day, or at least "carefully justify a decision to titrate dosage" above that level.

Although the CDC implies there is something special about these numbers, the study of opioid-related deaths in North Carolina found that "dose-dependent opioid overdose risk among patients increased gradually and did not show evidence of a distinct risk threshold." Critics see the CDC's cutoffs as arbitrary, since patients vary widely in the way they metabolize and respond to opioids, especially if they have developed tolerance after years of treatment.

"There seems to be no clear clinical evidence that opioid risks increase with 50 MME/day or that doses should never exceed 90 MME/day in any patient," Pergolizzi et al. write. "It seems unnecessary and counterproductive to decrease a patient's dose of opioids just to achieve an arbitrary limit."

CDC officials say they do not want doctors to impose dose reductions on patients. "We do hear stories about people being involuntarily taken off opioids," Deborah Dowell, a co-author of the guidelines, said at an April 2017 conference. "We specifically advise against that in the guidelines."

That's not exactly true, but the guidelines do describe tapering as a consensual process. The CDC says "clinicians should work with patients to reduce opioid dosage or to discontinue opioids" if they determine that the risks outweigh the benefits. It notes that "tapering opioids can be especially challenging after years on high dosages" but says "these patients should be offered the opportunity to re-evaluate their continued use of opioids at high dosages."

In many cases, that "opportunity" has become a unilateral decision. "Even though it is not specified in the CDC guidelines to do this," Kertesz says, "I am seeing many physicians in my region and across the country taper patients against their will. They're tapering stable patients who were not violating the rules of the practice, who were basically functional. Physicians are tapering them without consent, often in a draconian fashion, and in many cases simply discharging the patient from the practice and just ending the clinical relationship."

Lynn Webster, a pain researcher and former AAPM president, says he gets emails almost every day from desperate patients. Many had been taking doses of opioids that controlled their pain well enough for them to work and "have a reasonable life…maybe for a decade or more." Now, "because they're being forced to take a dose far less than what has been necessary to keep them functional," they are bedridden.

Other patients "have been told by their doctors that they're taking them off all of their medicines," Webster says. Many of them "don't have any idea where to go to get help." Some say "the only option they have is suicide."

Kertesz quotes a doctor at "a large integrated care system" who reported that "the situation of chaotic and involuntary tapers was brought home to me by a patient who shot himself in our parking lot." That patient survived. Others have not.

Lamb, the pain treatment activist, has compiled a list of two dozen patients who have committed suicide in the last few years after they were denied adequate pain treatment. They include Allison Kimberly, a 30-year-old Colorado woman with interstitial cystitis, who killed herself in June 2017 after an emergency room turned her away.

"I was rushed to the ER because my pain was so out of control I couldn't take it anymore," Kimberly wrote on Instagram. "I got ZERO help. After 7 hours I was discharged. The nurse has the nerve to say that my kind of pain shouldn't be that bad and basically I was faking for medication. I am so beside myself I am shaking as I type this. Screaming and begging in pain, needing any kind of help they'd give me and I was just sent home."

Kevin Keller, a 52-year-old Navy veteran with severe pain following a stroke, shot himself in the head with a friend's gun in July 2014 after the local V.A. hospital cut his opioid dose. "SORRY I BROKE INTO YOUR HOUSE AND TOOK YOUR GUN TO END THE PAIN!" he wrote in a note to his friend. "FU VA!!! CAN'T TAKE IT ANYMORE."

Keller's dose reduction seems to have been part of the department's so-called Opioid Safety Initiative, which began in October 2013. A Veterans Affairs "fact sheet" brags that the program reduced the number of patients receiving opioids by a third. According to a V.A. analysis, "opioid discontinuation was not associated with overdose mortality but was associated with increased suicide mortality."

Lamb says the medication he uses to control his pain, fentanyl patches supplemented by hydromorphone pills, is "the difference between wanting to put a bullet in your brain and enjoying life." Despite the huge improvement opioids have made for him, Lamb had a hard time finding someone to continue his treatment after his doctor curtailed his pain practice in 2017. Most physicians in his area "explicitly state they do not do medication management," he says. "I've been having lots and lots of trouble finding another physician. If I can't find one, the natural physiological consequences of severe pain will kill me."

Kertesz says "our focus on pill control" is driven partly by "a recognition that there was a failure to prescribe carefully" but also by "institutional and legal interests seizing on what looks like a simple answer to a complex problem," heedless of the human costs. "We're engaged in a stampede that is trampling people to death," he says, "and those people need to be protected."

Lauren Krisai, a senior policy analyst with the Justice Action Network (and formerly director of criminal justice reform at the Reason Foundation), provided research assistance for this article.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "America's War on Pain Pills Is Killing Addicts and Leaving Patients in Agony."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"It's horrible. I can't expect to live a life like this. I'm not a junkie. I'm not a threat to society. I'm not a threat to myself. I simply want to live my life without pain."

You, my friend, are one of the eggs needed for the oh so tasty omelette ordered up by soccer moms and the criminal justice industrial complex.

Exactly. We need to do the opposite of whatever makes sense. I think you can a whole bunch of other demographics to that list of nanny's.

I cannot sleep at night, very often, because I worry about terminally ill cancer patients on their deathbeds, with a mere month or two left to go, in HORRIBLE excruciating pain...

And some damned pill-mill, pill-pushing drug-fiends-enabling "doctor" goes and gets them... Prepare for it now...

HOOKED ON PAIN PILLS!!! This must be STOPPED, and NOW!!!

Thanks to Government Almighty, Jeff Sessions is ON THE PROWL against these pill-pushing FIENDS!!!!

Big Pharma has used the feds to keep marijuana illegal. Now comes kratom, still legal in most states and the US, but, like marijuana, it threatens Big Pharma profits. So, after its gambit using the DEA failed in 2016, Big Pharma is using the FDA to try to ban kratom. What's kratom? See "Newbie kratom dose model" on reddit: The drugs buprenorphine / naltrexone are standard opioid addiction treatment, costing $4-$8 / tablet. Compare that to kratom at $0.50 / 5g. Another drug kratom can replace is Viagra costing ~$70 / tablet.

There are no addicts.

People in chronic pain chronically take pain relievers.

Owen . although Howard is impossible, yesterday I got themselves a Mitsubishi from making $7338 this - five weeks past and just over ten k lass month . without a doubt its the coolest job I have ever had . I actually started 3 months ago and straight away began to earn minimum $83 per-hour . go to this site

look here more

http://www.richdeck.com

We know the cause of addiction.

Dr. Lonny Shavelson found that 70% of female heroin addicts were sexually abused in childhood.

Addiction is a symptom of PTSD. Look it up.

The NIDA says Addiction Is A Genetic Disease

until I saw the paycheck of $8554 I did not believe friend was like actualy bringing in money in there spare time at their computer there brothers friend has been doing this for only about 23 months and at present repaid the morgage on their home and got themselves a Mitsubishi Evo read this article

look here more

http://www.richdeck.com

This mans story reads like my diary. Family history of DDD, very active until I hear a "pop", four of them in my case. Never abused my medicine, now I'm under constant scrutiny, receiving only a small fraction of what I need. Most days I don't even want to get out of bed. The law says doctors MUST provide pain relief when necessary. So much for laws.

I think they would rather drive us into the streets or just crawl away and die...

I think they would rather drive us into the streets or just crawl away and die...

You're wrong. They don't think of you at all.

So true. When I had the flu last month, I was in line at the pharmacy and the pharmacist was having trouble filling my tamiflu rx. The guy in front of me was older, and he said "Welcome to medicine in the US, where no one gives a shit about you." I looked at him funny, and he said "Don't worry, they don't care about me either, and I'm a physician."

The good news is this guy is spending his retirement teaching medical ethics at HMS, which is nearby.

Contrary to the impression left by most press coverage of the issue, opioid-related deaths do not usually involve drug-naive patients who accidentally get hooked while being treated for pain. Instead, they usually involve people with histories of substance abuse and psychological problems who use multiple drugs, not just opioids.

So - explain the reason for the nearly 400% increase in overdose deaths from 1999 to 2016 (and 1000+% growth in ER visits/etc - which indicates the 'victims' are a different demographic than before 1999 or so). That sort of growth does not happen randomly or naturally (as eg the explanation of 'histories of substance abuse or psych problems). In any other phenomenon, it only happens with contagion - or very effective marketing/sales.

It is easy to see the subchanges that occurred around 2011 in those trends when doctors began changing their own behaviors. Followed unfortunately not by overall stabilization of deaths but merely stabilization of one subcause of deaths (pure prescriptions) offset completely by an increase in multi/illegal opioids. Such that the overall trend itself DID NOT CHANGE AT ALL. But that is clearly the result of one major observable systematic set of human actions which tried to deal with one side of the problem (creating new addicts) without addressing the other part (reducing existing addicts).

You OTOH want to pretend the ENTIRE trend is simply random and unexplainable. That is UTTERLY DISHONEST CRAP.

I think you must have stopped reading after you reached the paragraph that set off your temper. Sullum is well aware of the increase in opioid-related deaths, and spends a large portion of the article discussing causes.

His article and proposed suggestions could have been written in the 90's.

I have always been sympathetic to the notion of treating this sort of thing as more of a public health issue than as a criminal issue. But the implications of that when the problem is small and marginal are completely different than when the problem is the MAIN healthcare cost element for, say, ages 18-50. And he is almost entirely ignoring that.

In the former case, there is little opportunity cost as long as there is spare capacity because healthcare is mainly fixed-cost. In the latter, the opportunity cost can be crippling - esp since addicts have virtually infinite capacity (and willingness) to bleed everyone else dry without a second thought. And esp since in the US those opportunity costs are going to be of the form 'deny poor non-addicted person access to healthcare because poor addict is jacking up prices out of reach'. A lot of demonized 'drug warriors' are just moralizers. But I know of many who are FAMILY of addicts who understand that they do not stop until they are coerced (OD death being one effective form of coercion).

And yet - here again is an article that is basically pretending the problem is still one of mere moralizing rather than - now - significant cost externalities in a country that absolutely SUCKS at delivering healthcare to many who are FAR more deserving than addicts.

And who, besides God, has the right to make that decision?! Addicts are NO LESS DESERVING of a long, healthy, life. Self righteous "people" seem to be more of the obstacle of reducing the harms of addiction. Addiction is the real problem. Just, maybe, we should be thinking outside of the box for treatment. Since, the past 100 years of the same mistakes, made over and over, have not done anything to reduce the overdose problem. (Einstein would call that insane!) All the while, it increases the suffering of people with chronic pain, like me. Me, who is, also, a physician who was destroyed by the ignorance of the less compassionate physicians in medicine. The addiction rate, quoted in this article, has been the same since the turn of the last century. The chronic pain patients have less addiction than the general population. But, we physicians have to watch our patients take their own lives because there are many things that are worse than death. One of them being chronic unrelenting, intractable, untreated (or under-treated), severe pain 24/7. If it comes down to it, I will not suffer in pain.

But, what about those people who only get relief from properly managed pain. Sadly, interdisciplinary pain management is not available to the people that need it. Most insurance won't cover it. It costs too much!

Michael G Langley, MD, Past fellow, American Academy of Pain Management. Past board certified general surgeon, retired/disabled.

And who, besides God, has the right to make that decision?!

Whoever is expected to pay for the decision.

Most insurance won't cover it. It costs too much!

Even if 'insurance' covers it, there is no magic insurance tree. God ain't opening up his wallet here either. Don't misunderstand me. It isn't that I don't have compassion, it is that compassion is not the issue or the solution. The issue is someone else is being expected to pay, the money is going to extremely well-paid providers who ain't reducing prices and ain't covering the costs of their created-addict mistakes either, and those who are suffering the pain have an associated history of using 'compassion' in order to create guilt in those they manipulate.

The proposals in this article and from all the experts were maybe doable 20 years ago. Or now in a country that has eviscerated the teat-sucking cronies in their medical system. But those same experts spent the last 20 years making the problem multiples worse than it was then - and they ain't taking one FUCKING bit of responsibility for their screw-ups/incompetence - and wotta surprise guess who's supposed to keep subsidizing/enabling all the bullshit because - compassion.

I am afraid you make no sense whatsoever. As the article points out, many of those denied prescription meds, who don't become confined to their beds and or suicide, turn to street medications, none of them produced by big pharma or foisted upon the public by evil doctors. Those in chronic pain are not offered the opportunity to pay for pain medications except on the black market, where drugs are of unknown quality. Many are forced to pay for black market pain relief and do so. The question is not how much pain meds cost (some like methadone are dirt cheap) . It is whether of not patients have access to pain medications at all. And today in most of the United States, due to an ongoing hysteria based on lies, they don't. It is simply too much trouble and too dangerous for doctors to prescribe effective pain relief. Where the Federal government got the right to practice medicine remains a mystery.

So I suppose we need to ban Doritos, McDonalds, and deep fried candy bars too. Except none of those are necessary for some people with severe chronic pain to lead normal lives.

It would help very much if you stopped using the word "addiction" in these conversations.

People like myself and the subjects of this article aren't addicted to opiates, we're physically dependent on them. That means we're unable to function normally and will die prematurely if we don't use them. No different from a person who takes medications for hypertension or diabetes.

It's nothing to rejoice about. We don't get "high" from these drugs at all, most folks don't get that. Calling us "addicts" is just cruel and bigoted. I've broken my spine 4 times in the service of the larger society as a K9 search and rescue handler. I didn't do it for fun. Now I can't do any of the things I used to.

Would anyone like to explain why my needs for chronic pain medication should be subject to me neighbor's approval? Seriously. Medical doctors spend decades getting qualified to make these decisions and all the sudden I'm supposed to accept some congressman's qualified opinion? What's going on here?

Is that you Kolodny?

To answer your question, I can explain it. A couple of generations of dirtbags with the addiction gene have decided to off themselves. Normally I'd think it's a tragedy, but like most of the people on here who suffer from chronic intractable pain, my main worry is being able to live a fairly normal and fruitful life. So hopefully, once these dirtbags die off, regular law abiding people like me who have pain through no fault of my own won't be treated like dirtbag addicts anymore.

I like the idea of offing people with bad genes. Are there any other groups that deserve this sort of attention?

Just the people who have destroyed innocent pain patients' lives aka the dirtbag addicts who stick needles in their veins.

This country can't be rid of them quickly enough.

PS Thanks for the weak attempt at race baiting.

The increase in overdose deaths was caused by the fact that when doctors institute sudden cut-offs of opiate prescriptions without humanely helping the patient wean down off the drug, it results in thousands of ordinary pain patients, in severe withdrawal, going into the streets to try and find their medication from illegal sources. These people discover that the main drug available is heroin, and it is now often cut with lethal doses of fentanyl, so that what you think is your necessary dose is now killing you. This is the direct consequence of threatening doctors with jail if they do not stop prescribing opiates. It is inhumane in the extreme. People who depend on opiates to be able to live a normal life are not addicts seeking excessive drugs to get high.

This is the same thing that happened in the 70s when Nixon declared the damned war on drugs to begin with. It took a generation of inhumane treatment of people in pain before the medical establishment realized there was a severe issue of human welfare in denying people effective pain medication. God only knows where the current (and recurrent) hysteria will end this time.

What government war on opioids? There are enormous numbers of people taking these opioids. In the tens of millions. It's much cheaper, after all, to pawn off pain pills on patients than to actually attempt to treat underlying ailments. These pills are obtained legally through traditional channels which the government watches over.

Either you didn't read the article, or you can't read.

I am prescribed narcotic opioids following 3 lumbar spine surgeries. While the surgeries did increase my mobility, they did little for the pain and I now have a bunch of hardware in my back and moderate to severe nerve damage that causes intractable pain. I've done steroid and analgesic injections, nerve ablation, and physical therapy with little results, very temporary and extraordinary expense (often $3-5,000 per procedure, not covered by insurance or all to deductible) out of pocket.

For me, prescription medication is both affordable and effective, and as the owner of my body, I choose the meds. I'm not an out of control junkie; I'm functional both as a parent and business owner. Without the medication I'm miserable, depressed, and can barely get out of bed. For someone not in my position it's easy to say "suck it up and deal with it", but I doubt you'd say the same actually in this or a similar position.

I have full faith in my doctors who very conscientiously review my dosages and their effectiveness quarterly. I hope the government doesn't come between myself and my doctor. What I have now works; without it I can see why some people would consider suicide.

Govt (or someone) is gonna get between you and your doctor eventually. Because the reality everywhere in the world is that healthy people pay the medical costs of sick people - and true 'insurance' cannot exist if sick people are then, alone, determining the extent/nature of those expenses.

The US is simply the only country on Earth which is incapable of even thinking about that unpleasant reality.

Do you know the retail costs of prescription pain medications ? Fetanyl 5 patches (2 weeks supply) 25 mcg is about $45.00, 75 mcg about $100. (75 mcg is a medium dose). Hydromorphone (dilaudid) is $23-$40 per hundred $mg tablets. * mg is about the maximum dose you can take and stay awake. They last about 4-6 hours. If you are suffering from serious chronic pain you would use a fetanyl patch or patches to provide sufficient pain relief to function and sleep, and use dilaudid for break through pain, for example if a spasm woke you up and prevents you from going back to sleep. Two 4mg tabs 3-4 times a day is most anyone would ever take. So it would likely cost maybe $250.00/month to relieve, as best medicine can, severe chronic pain if the patient covered the cost entirely. Methadone is a more difficult drug to use safely than fetanyl or morphine (hydromorphone) and requires closer physician supervision. But it is dirt cheap. The maximum recommended safe daily dose is 40 mg. 120 40 mg. tablets cost about $25.00. So a years supply is $100. Private insurance usually partially covers prescribed medications including pain medications. Why you think pain management needs to be government subsidized or cannot exist in a completely free market is incomprehensible (at least to me).

I have "medical" insurance but it never pays for the pain meds. They always find some reason to deny the claim. Mine cost about $55/month.

As far as the OP's comment goes, no one has ever paid my medical insurance premiums but me. I've spent well over $1 million on medical insurance premiums over the past 50 years. I suggest you take a seat and put a sock in it.

$1,000,000 in premiums over 50 years? That's an average of $20,000 a year. Between inflation and insurance costs increasing with age, I would expect your current premium to be significantly higher then the average.

And you still can't get 'em to cover your prescriptions? Time to change insurance dude. Or possibly just drop it, since if you can afford such exorbant premiums, you can probably pay for shit out-of-pocket.

If you live in the US, and buy your own insurance, or have one through work, everyone is paying for your kids healthcare, vision etc. We are also paying for maternity and paternity leave.

If I'm say 60 and have a chronic condition, and my kids are grown,,and you're 30, who is paying for what? We are both subsidizing the other.

So please stop blaming the high cost of insurance on people with preexisting conditions. It's also caused by the other 11 points that obama decreed constitute a true insurance plan, like me paying for you to have a kid.

See how this works?

"I am prescribed narcotic opioids following 3 lumbar spine surgeries."

There are 10s of millions prescribed these opiates, very strong drugs, as you are doubtless aware. There must be cases where you doubt the doctor's judgement, given their enthusiasm for this sort of treatment.

mtrueman,

I find your reply hard to understand, since who you replied to is touting the success of his treatment, as prescribed by his doctor. Would you rather that the doctor/patient relationship be determined by some third party, like you....(;-P....? Not very wise, IMHO! Who the hell would not be enthusiastic about a treatment that restores a semblance of a life?! "Very strong drugs" seems to imply that you are very unaware of dose, tolerance, tirtration, and the entire nuance of pain management. Strength of the drug only implies the dose the patient is to receive. The "highly addictive" crap is just as stupid! Something is addictive or it is not! You should leave that judgment to the professionals!

mfalseman is a stupid pile of shit. Ignore it.

I have had legitimate, severe, life altering pain for most of the last 30 years, and I have never found it easy to find doctors to treat my pain, and this includes the so called heyday of narcotic prescribing in the US (late 90s). So please stop spreading this fallacy that it's simple to obtain scripts for these meds. Thanks.

People with illegitimate pain are ruining it for everyone.

This isn't a joke. People who have pain through no fault of their own are being turned away as addicts, while the addicts are being treated humanely.

Wtf has happened here? It's like when Taylor saw the buried Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes....it's like the world is upside down.

Your ignorance is showing. Too bad you did not read the article. It completely answers you ignorant claim! But, it does allow you to completely think you are better and brighter than the rest of us!

mtrueman owns an autographed pucture if Rick Santorum. So he is and he knows he is better than us.

Snarkiness aside, if I'm ever on a jury for someone charged with possession for paun management I'm not funding them guilty. Ever.

How pleasant it must be on your world where all diseases, injuries and ailments can be successfully treated. Since no one dies it must be pretty crowded though. If you lived on Earth and tried to get a prescription for pain medications effective for serious pain you would realize that it is extremely difficult and all too often impossible. If you are objecting to the phrase"war on opioids" and would prefer "war on those in pain" you might have a point.

these evil sons of bitches should all get afflicted with a debilitating chronic pianful condition.

As a prescriber, please let me put Craig into perspective. His story seems very plausible although it's patently unwise to set aside a segment of your controlled substances and then travel with them because when that happens, that week worth of pills outside the prescription bottle no longer looks like a prescription, and instead looks like a weeks worth of hillbilly heroin he scored from someone else who was selling off their ill-gotten prescription that was already subsidized by taxpayers. The reason prescribers no longer want to deal with "I forgot some of my pills in a suitcase" excuses is because every...single...patient who takes a controlled substance every day has a story about why their count is off. The bottle tipped into the toilet. My cousin stole them...but no, I'm not calling the police. I need something different because I took one and it didn't work so I threw the rest in the garbage....the litany of lies is endless. A primary care provider will prescribe a month's worth of hydrocodone, and when the patient returns for a refill with an empty bottle, their drug test will come back for benzodiazapines and amphetamine...but not a nanogram of opiate in their toxicology screen because they were selling their hydrocodone to buy crushed Xanax and meth. And oddly, I never get patients in the ED who's toilet swallowed all their pills for blood pressure or diabetes. It's like there is a magnet in those toilets pulling in only controlled substances.

This constant train of lies and non-compliance make these patients a disruption to and already-stressful clinical practice, and that is why providers don't want to deal with it anymore. Add to the fact that these patients are most often aggressive and ignorant to front line staff and providers, and they are not worth the hassle. Craig may be different, but until I read his provider's side of the story, I'll take Craig's with a grain of salt.

Next, Craig us a daily user, and that has nothing to do with the preceding commentary about people who take post-operative opiates. He is well past that stage and is not even taking the same kind of opiate as is prescribed in the post-operative phase. Clinicians are well-able to tell the difference, so the article is disingenuous in their blurry segue in that first segment.

Prescription monitoring is essential. Without it, patients will hop around visiting emergency departments, urgent care clinics, and their provider's office to stock up on prescriptions which they will then fill at a variety of pharmacies to avoid suspicion. Being able to check the database actually makes me more inclined to provide a prescription to someone who's record does not show a pattern of clinic-shopping.

The one element of this article that is profoundly true is the gov't war on drugs. My practice has shown me that most people who use marijuana routinely for therapeutic reasons become patently indifferent about obtaining any other drug. There will undeniably be side effects (which can be fatal or disabling) as more people use more frequently and for longer duration, but so far those effects are easy to treat, and those patients are not clogging up the waiting room demanding opiates from me and calling me a useless racist when I decline to fill out another prescription.