The 2010s Have Been a Banner Decade for Unintended Consequences

The war on drugs looks crueler by the day.

The 2010s are proving to be a banner decade for unintended consequences in America's war on drugs. By now, readers are likely familiar with the policies that bolstered the markets for heroin and then illicit fentanyl: Law enforcement cracked down on doctors who prescribed large amount of painkillers, pharmacists were required to report opioid prescriptions to government databases, and regulators asked the pharmaceutical industry to make pills harder to manipulate. Unable to access snortable or injectable pills, users turned to the black market. As a result, prescription overdose deaths have declined in many states, but fentanyl- and heroin-related overdose deaths have skyrocketed.

The New York Times reports that two other substances are also having a moment. "Overshadowed by the Opioid Crisis: A Comeback by Cocaine," reads a Times headline from Monday morning. "Meth, the Forgotten Killer, Is Back. And It's Everywhere," the Grey Lady declared in February.

Neither drug really went away—only Quaaludes have ever done that—but they are cheaper and more plentiful than they have been in years, thanks to supply reduction policies enacted by the United States and its allies. The Times tells us, for example, that a

study by RAND found that cocaine consumption fell 50 percent between 2006 and 2010. But in the past few years, the cocaine supply from Colombia has climbed to a record high in part because of a peace settlement that includes payments to farmers who stop growing coca. To be in a position to qualify for those payments in the future, many farmers started growing it. As a result…cocaine prices have fallen, leading to an increase in cocaine use in the United States and some European countries.

The Economist says farmers in Colombia knew for years before the peace settlement was completed that the government would eventually pay them to stop growing coca, which is a very good reason to not grow anything else until the checks start coming in.

Stateside, cocaine is cheap and, in many places, contaminated. Last week, Harm Reduction Ohio reported that cocaine samples across the state tested positive for illicit fentanyl and its analogs, meaning cocaine users with no opioid preference (or tolerance) are playing Russian roulette every time they put schnozz to mirror. People who intentionally mix heroin and cocaine, meanwhile, are increasingly likely to shoot those two plus fentanyl.

The result is more dead cocaine users.

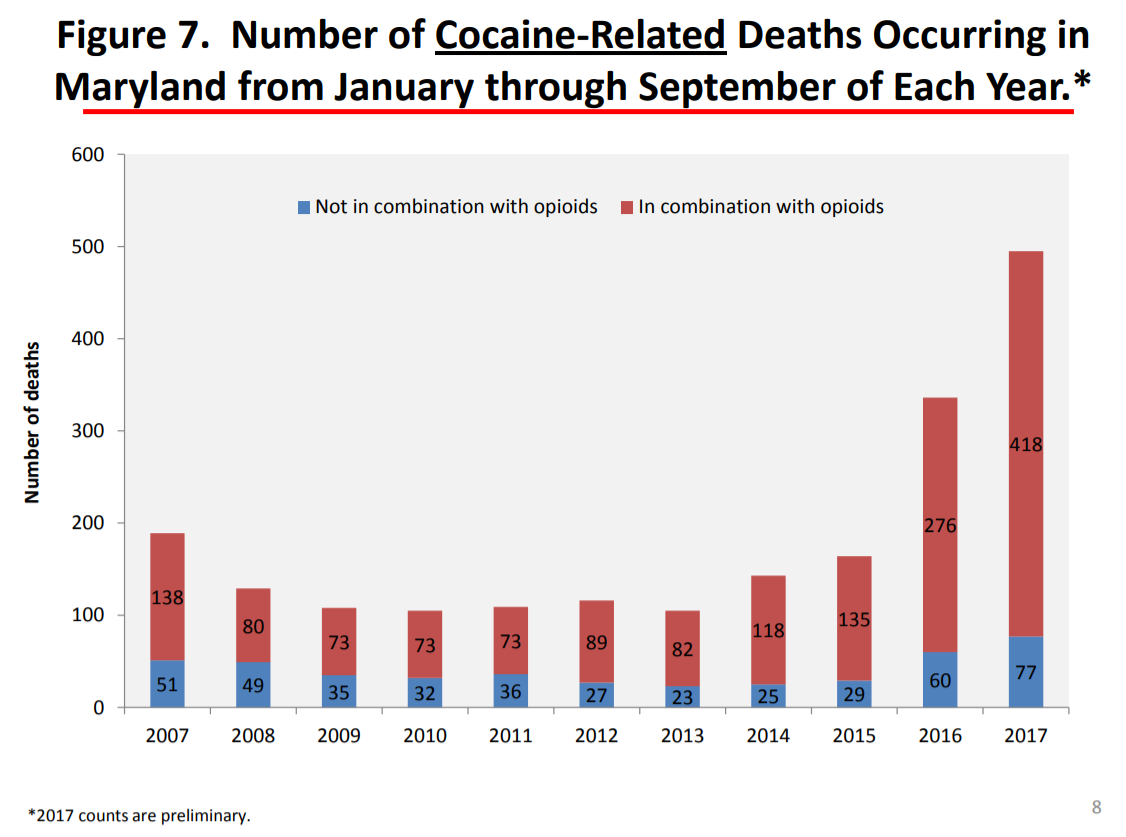

Back in December, the pseudonymous blogger Jubal Harshaw emailed me with some data from the Centers for Disease Control showing that cocaine overdose deaths involving fentanyl had increased from 23 percent of cocaine deaths in 2015 to 40 percent in 2016. In Maryland, the number of opioid-cocaine deaths has increased dramatically:

A large number of overdose deaths have always involved more than one drug. Classically deadly combinations include opioids plus alcohol and opioids plus benzodiazepines. Mainstream reporting seldom covers the crisis with that much nuance, but now's as good a time as any to split hairs, per a recent Vice dispatch:

One CDC report found that nearly half of such ODs nationwide involved consumption of drug cocktails, and in New York City, the local health department has repeatedly reported that upwards of 90 percent of overdoses involved the interaction of multiple drugs. In Ohio, meanwhile, a study in 2015 found that the cause of death for 73 percent of overdose victims was linked to more than one drug—and nearly a quarter had four or more drugs listed.

As for meth: The Times wants you to know that it's still around and still very bad. This sequence of paragraphs is particularly illuminating:

Here in Oregon, meth-related deaths vastly outnumber those from heroin. At the United States border, agents are seizing 10 to 20 times the amounts they did a decade ago. Methamphetamine, experts say, has never been purer, cheaper or more lethal.

Oregon took a hard line against meth in 2006, when it began requiring a doctor's prescription to buy the nasal decongestant used to make it.

"It was like someone turned off a switch," said J.R. Ujifusa, a senior prosecutor in Multnomah County, which includes Portland. "But where there is a void," he added, "someone fills it."

It's almost like a Rorschach test. Do you see supply-side regulations that fail to address the underlying problem—an inelastic demand for self-medication, intoxication, or some combination of the two—as requiring more supply-side regulations, such as a wall, stiffer penalties, more prisons, more bans? Or do you see our repeated failures to eradicate the illicit drug market as evidence that the world is too big and complicated to control, and thus that the most sensible and compassionate response to the multiple drug crises we are now experiencing, and the hepatitis C and HIV epidemics we appear to be on the verge of experiencing, is to reduce harm via decriminalization and deregulation?

Show Comments (80)