Why the Senate Tax Reform Bill Is a Big Deal for Gig Economy Workers

The newly released bill would clarify Uber drivers' and Airbnb hosts' status as independent contractors but would require tax withholding.

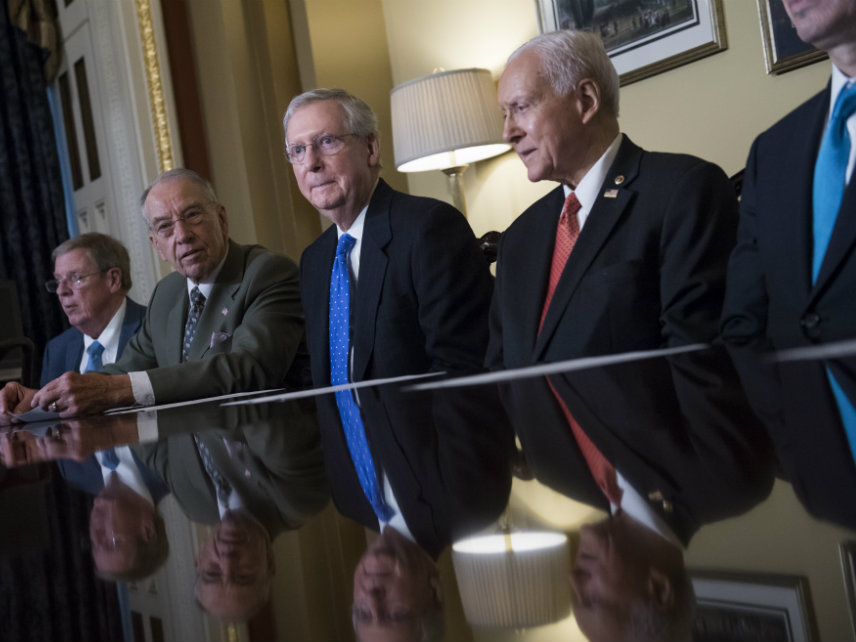

A key provision in the tax bill that Senate Republicans unveiled yesterday clarifies the role of workers in the so-called "gig economy." It also sets up a showdown over whether platforms like Uber and Airbnb will be required to withhold taxes on behalf of their users.

As I detailed in a Reason feature back in September, the current federal tax code—last updated in 1986, long before Uber, Airbnb, and the rest of the gig economy came along—fails to adequately account for the estimated 2.5 million Americans who earn income through on-demand platforms every month, according to an estimate from JP Morgan Chase. There have always been independent contractors, of course, but their numbers have shot upwards over the past decade as online platforms made it easier than ever to offer rides, lodging, or other services at the tap of an app. Many workers who sign up to drive for Lyft or sell homemade goods on Etsy are unaware that they are also signing up for a far more complex tax status by earning a few hundred dollars in a side gig.

The tax debate offers a rare opportunity to fix some of these problems. The Senate version of the tax reform bill makes a solid attempt at doing that by including portions of the South Dakota Republican John Thune's New Economy Works to Guarantee Independence and Growth Act—the NEW GIG Act.

Thune's legislation clarifies that gig economy workers are independent contractors, and that neither service recipients nor third party apps are employers. At the same time, the bill would require gig economy businesses to withhold income tax from their contractors—a provision that would ease the confusion facing Uber drivers who might expect income tax to be taken out of their pay in the same way it is for W-2 employees. Thune says his bill "would provide clear rules so these freelance-style workers can work as independent contractors with the peace of mind that their tax status will be respected by the IRS."

Researchers at Boston College and American University have found that gig economy workers confused by their status as independent contractors, or by other elements of the tax code, often do not pay taxes at all or have to hire expensive tax help to figure out what they owe on a relatively small income.

Thune's proposal would also set a new reporting threshold for all miscellaneous income earned by independent contractors. Workers who earn less than $1,000 would not have to report their income at all, while those who earn more would. Under current law, this threshold is a bit fuzzy. Some income is subject to reporting after $600 is earned, but credit card payments that total less than $200,000 do not—unless the income was earned via 200 or more separate credit card transactions.

A similar bill has been introduced in the House by Rep. Tom Rice (R-S.C.) and could be incorporated in the House version of the tax bill, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. (The House and Senate bills both use the same name, despite some differences in substance.)

The potential sticking point has to do with the idea of requiring sharing economy platforms to withhold income taxes from their users. As written, the Thune amendment would require income tax withholding as part of a three-pronged test that grants independent contractor status to gig economy workers. The platforms themselves want this clarification included in the law as a way to short-circuit lawsuits, like one already launched by Uber drivers in California, aimed at forcing them to treat workers as employees.

In return for clarifying that gig economy workers are contractors, Congress appears to be saying, those platforms will have to collect income taxes from those same workers. By doing that, Congress guarentees that more taxes will be paid—rather than the current system, which relies on individual contractors to correctly calculate and pay their own taxes, something that likely shortchanges the IRS to the tune of several billion per year, according to Caroline Bruckner, managing director of American University's Kogod Tax Policy Center.

Congress cares about capturing those unpaid tax dollars because it has to find a way to "pay for" the GOP bill's $1.5 trillion in tax cuts. Republicans plan to pass the tax reform bill through the Senate with a simple majority using the reconcilliation process, which can only be used on bills that adhere to the Byrd Rule and do not increase the deficit outside of a 10-year window.

"They'll likely be looking for money, and platforms like Airbnb which process transactions for sharing economy hosts and guests will look like attractive targets," says Romina Boccia of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C.

But mandatory withholding could stifle innovation and competition in the gig economy, because it would add to the start-up and overhead costs of new online platforms.

Instead, Boccia suggests, lawmakers should allow workers on gig economy platforms to opt in to tax withholding. That would be a win for everyone. Platforms would get clarity about the employment status of their workers; workers would get the option to simplify their tax prep by having taxes withheld; and Congress would not impose mandatory costs on future gig economy platforms.

In all cases, flexibility is the key. Gig economy platforms say they expect to see participation in the "on-demand economy" rise from 4.4 million workers today to approximately 7.6 million in 2020. Lawmakers in 1986 could not have expected this surge in independent contracting, and lawmakers today should be prepared for the economy to keep changing in unexpected ways.

Show Comments (64)