Breaking Addicts in Order to Fix Them

How Synanon revolutionized drug treatment and poisoned the politics of prohibition.

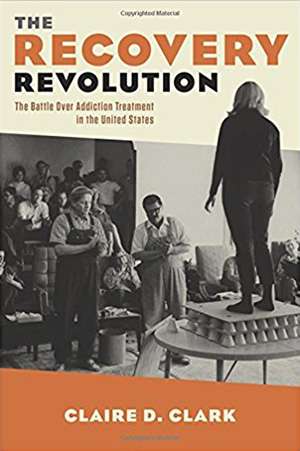

The Recovery Revolution: The Battle Over Addiction Treatment in the United States, by Claire Clark, Columbia University Press, 336 pages, $35

Though nearly forgotten today, Synanon—the first organization to claim to have a drug-free cure for heroin addiction—had an enormous impact on American culture. At the peak of the drug war of the 1980s and early '90s, at least half of all publicly funded addiction treatment was based on its model of communal and intensely confrontational living.

Synanon was founded in 1958 by Chuck Dederich, a member of Alcoholics Anonymous who felt that A.A. wasn't tough enough. (Dederich claims to have coined the popular self-help phrase, "Today is the first day of the rest of your life.") By the mid-1960s, it had evolved into a California-based commune widely celebrated as the counterculture's antidote to drugs, and populated by hipsters, Hollywood stars, and jazz musicians. In those days it was lionized by Life magazine, the major TV networks, and even a 1965 Columbia Pictures film; Milton Berle, Jack Lemmon, and other celebrities promoted it.

But then came word—and later proof—of child abuse and beatings for non-compliance of both adults and children. Dederich decided that members' children were a drain on the community, so he pressured men into having vasectomies performed by Synanon doctors on the spot and ordered women to get abortions or be forced out. "Marathon" groups extended for days without food or bathroom breaks, featuring sadistic emotional attacks on those who were seen as backsliding or disloyal.

To the extent that it is remembered now, Synanon is probably best known for having put a four-and-a-half-foot-long de-rattled rattlesnake in the mailbox of an attorney who was starting to win legal cases against it. Among journalists it also has the notoriety of winning the largest libel judgment in history, after Time called the group a cult in 1977. Only later was the truth about the organization fully established, thanks to the courageous reporting of the small-town Point Reyes Light, which won a Pulitzer for its exposés in 1979.

Claire Clark's The Recovery Revolution prefers to emphasize the positive. The book doesn't even mention that snake attack, nor the fact that Dederich was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder as a result of it.

Perhaps the author wanted to avoid covering familiar ground. But by failing to explore how Dederich and Synanon set the precedent for the abuses she chronicles in later programs based on it—and by failing to wrestle with how those harms stemmed directly from its structure and practices—she undermines her credibility as an objective observer.

Worse still: Even though a great deal of evidence suggests that the methods pioneered by Synanon do more harm than good, she doesn't mention any of this scholarship. Instead, she uncritically accepts studies that claim to show that what has become known as the American "therapeutic community" is an effective model for addiction treatment.

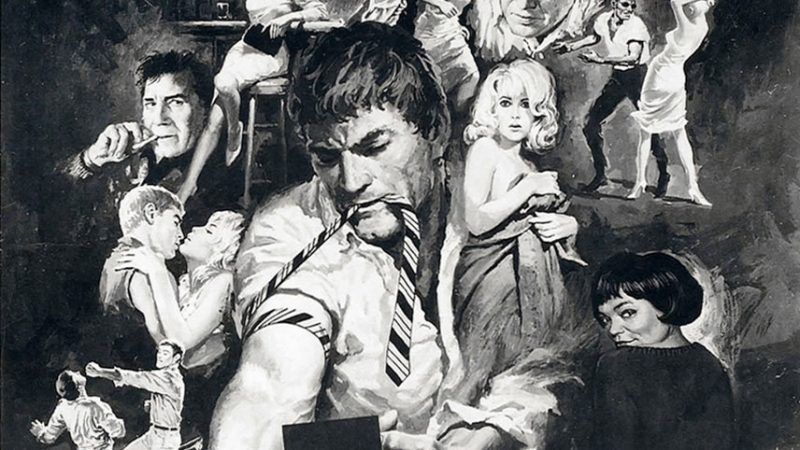

Synanon made it acceptable to use tactics in treating addiction that had long been seen as barbaric when used for mental or physical illness. Since the group's core idea was that the "addict" personality was marked by "character defects," Synanon aimed to eradicate it by brute force: shouting abuse at participants for hours and even days on end, spitting in people's faces, humiliating them by making them dress in diapers or drag, and combining food deprivation, sleep deprivation, and relentless confrontation in an attempt to erase a person's old identity.

Not a single study shows that these methods are superior to kinder, safer approaches. Indeed, researchers have shown conclusively that shame, punishment, confrontation, and humiliation are ineffective and often harmful in addiction treatment. As early as 1973, a study of Synanon-led groups showed that attack therapy led to lasting psychological damage in 9 percent of the participants. While living in a supportive community has been shown to help people recover from addiction and mental illness, that is not what Synanon innovated. As the cliché goes, what was effective at Synanon was not original to it, and what was original was not effective.

Despite these failings, the book is well worth reading. Clark presents an excellent overview of the history of American addiction treatment, the ideological battles within the field that continue to plague it to this day, and the way that Synanon sparked dozens of imitators. Many of those imitators still exist in modified form, such as Phoenix House and Delancey Street.

And she makes a fascinating argument about the importance of the "ex-addict" activists who founded Synanon and its descendants. Essentially, she says that their political activism played a critical role in convincing America that treatment—not punishment—is the best way to deal with addiction.

Synanon created a genuinely radical community that embraced group living, racial integration, and emotional honesty while at the same time enforcing rigid hierarchy, authoritarian leadership, and conformity.

This apparently lefty/hippie group of outsiders bought into, and then sold others on, the idea of a drug-free America, creating a form of treatment so punitive and moralistic that it was easily embraced by the right. First lady Nancy Reagan called the Synanon-inspired Straight Inc. her "favorite" drug program and visited with teens there several times, once even bringing along Princess Diana.

Clark recognizes how ex-addicts with tales of redemption both improved their lot and undermined themselves by supporting this type of treatment. By promoting shame, humiliation, and moralizing as essential aspects of rehab, they were able to help America move away from simply arresting and incarcerating people. (Only within the last 10 years or so has the field begun to move away from Dederich's idea that confrontation and humiliation are necessary aspects of addiction "care," and to accept that people with addiction also deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.)

But by failing to challenge the idea that addiction is sin, these activists simultaneously supported continued criminalization and repression. Treatment is often offered as an alternative to incarceration, but when the "alternative to incarceration" involves being locked up in an even harsher environment, it's not much of an alternative.

Clark chronicles and analyzes many of the complexities of Synanon's legacy. But a better book would have addressed the damage it did to tens of thousands of people by legitimizing the dangerous notion that addiction therapy can't fix people until it breaks them first.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Breaking Addicts in Order to Fix Them."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Why no mention here of "Synanon and Scientology"? The two were / are married at the hip! Use "Synanon and Scientology" as Google search string...

Over the years, I have seen reluctance by "Reason" to criticize Scientology and other cults. What's the deal, too hippagrovalistically metrosexual and "tolerant" to honestly address the abuses of cults?

It's because Scientology beat the IRS, and beat them badly by using the IRS's own gestapo surveillance tactics against them. They followed agents, and, I guess, intimidated them.

That being said, the patents that Scientology has on their "therapeutic" technologies are all owned by former IRS lawyers, and Scientology has worked very hard to keep that info from becoming public.

I'm making over $7k a month working part time. I kept hearing other people tell me how much money they can make online so I decided to look into it. Well, it was all true and has totally changed my life.

This is what I do... http://www.startonlinejob.com

"A Modest Proposal"

Give free clean medical-grade heroin, as much as they want, to addicts. Once they finish killing themselves, they'll stop being a problem.

That's called 'heroin maintenance' or 'heroin assisted treatment' and has been show to be remarkably effective at allowing addicts to reconnect with family and friends, and re-establish the support networks that help them become non-addicts.

See http://drugwarfacts.org/chapter/hat for details and links to clinical data from research journals

unless you were just trying to make a stupid joke....

Note carefully that Keith Richards is still alive. The 'medical grade' aspect is a very important part of that picture.

Note that it is prohibition that causes street-dealers to use 'cuts' that are themselves deadly in some cases. Note that it is prohibition that prevents the vendors from being accountable, and prevents normal consumer protection laws for purity, and standard weights/measures labeling laws, from being enforced.

Note that when the prohibitionists get around to prohibiting tobacco (if you can't see it coming, take your blinders off!), the 'but boys' on the corner will be selling who-knows-what to unsuspecting buyers, and people will die.

Prohibition kills.

N_J

Let's implement Quitters, Inc.

I saw "Breaking" in the title and came here expecting a Bane reference...

I haz a sad now...

People in chronic pain chronically take pain relievers.

14 Year Veteran Undercover Cop Exposes Truth About The Drug War: "I Used To Believe I Was Doing Good"

"When I went into policing I thought addicts had made the mistake of trying drugs and had no willpower to stop. Actually, problematic drug users ? or at least all the ones I knew ? were self medicating. Most of the heroin users I knew were self-medicating for childhood trauma, whether physical or sexual.

Theological brainwashees sure put a lot of stock in brainwashing and social pressure. The truth is most people--especially sane people--dislike morphine drugs. Given a choice, even the trippiest of deadheads shuns the stuff. Only when teetotalitarian altruism crushes the life out of them have I seen people turn to that sort of thing, more as escape than enjoyment.