Once Dovish-Sounding Trump Getting Very Bad Foreign Policy Advice

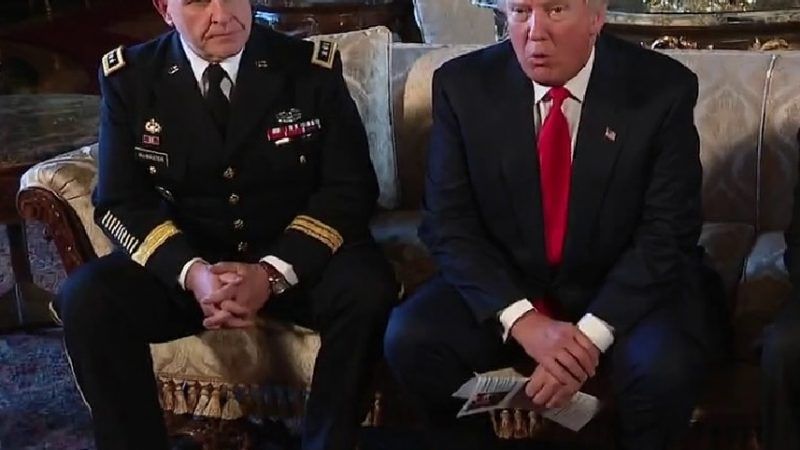

The president increasingly sounds like his national security advisor, H.R. McMaster. And that isn't good.

In April of 2016, New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd published a piece entitled, "Donald the Dove, Hillary the Hawk." For all his reality TV machismo, Dowd argued, Trump was in some ways a more dovish candidate than Hillary Clinton.

"The prime example of commander-in-chief judgment Trump offers is the fact that, like Obama, he thought the invasion of Iraq was a stupid idea," Dowd wrote. "He can sound belligerent, of course, saying that he would bomb the expletive-deleted out of ISIS and that he would think up new and imaginative ways to torture terrorists and kill their families. But he says that in most cases he would rather do the art of the deal than shock and awe."

Dowd built her case on a foundation of campaign- and pre-campaign-era comments from Trump pairing his personal "militarism" with pledges to eschew the interventionist missteps of recent history. The United States will "pursue a new foreign policy that finally learns from the mistakes of the past," Trump said before taking office. "We will stop looking to topple regimes and overthrow governments, folks. Our goal is stability, not chaos."

"Unlike other candidates for the presidency, war and aggression will not be my first instinct," stated then-candidate Trump. "A superpower understands that caution and restraint are really truly signs of strength."

Since Trump took office, Dowd's headline has become infamous and laughable. While Hillary remains a hawk, Donald is most definitely not governing like a dove or even, to use his own recent phrase, a subscriber of "principled realism." On the contrary, he has maintained or escalated all the reckless interventionism of his predecessors.

Trump has threatened preventive military action against North Korea and even Venezuela. He launched the first U.S. strikes against Syrian government targets and is said to be considering drone strikes in the Philippines. His August speech on Afghanistan pledged perpetual war and nation-building under another name.He is adamant about hiking military spending to pay for new, unjustified misadventures abroad, despite the Pentagon's unaudited books and long record of abundant waste.

Candidate Trump asked good foreign policy questions; President Trump has not given good answers.Realism and stability are nowhere to be found. What happened? Whither Trump's positive instincts, however inconsistent, against aggression?

In his Afghanistan speech, Trump explained his reversal as a mature response to his discovering the realities of the presidency. The more probable explanation is less flattering: Trump is heeding the advice of his top advisers.

These are establishment figures who have a more conventional approach to foreign policy. They are comfortable with the post-9/11 status quo of counterproductive interventions into the political affairs of chaotic, Middle Eastern, African, and East Asian countries. Where Trump once asked good questions, too many of his advisers have no such curiosity.

National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster is key in this dynamic. Trump once critiqued nation-building. McMaster has endorsed "state-building in places like Afghanistan and Iraq." Now, while claiming to reject them, Trump is making nation-building commitments.

Trump once expressed dismay at the length of U.S. military interventions. McMaster has championed "U.S. commitment over time" in Korea as a model of long-term occupation to be followed in the Mideast. Now, Trump has rejected his "original instinct… to pull out" of Afghanistan in favor of permanent commitment in pursuit of unachievable goals.

At one time Trump advocated fresh diplomatic engagement with North Korea. McMaster has hyped it as a threat that cannot be overstated and has threatened preventive war. Trump has now pivoted to talking of preventive "fire and fury," a military reaction to Pyongyang's all-too-common saber rattling.

The president clearly retains a special regard for military advisers, and McMaster's record and reputation—not to mention his display of the sort of rugged, movie-military bearing Trump is said to prefer in his administration—has made him a favored voice in the White House. Whatever his personal merits, it is clear McMaster's foreign policy ideas do not align with the better impulses, the inclinations toward realism, Trump showed as a candidate.

Trump's activist foreign policy lurch is substantial and may have done irreversible damage to U.S. interests already. It is difficult to believe the situation in North Korea, in particular, would have escalated so quickly had Trump not abandoned diplomacy in favor of a juvenile tit for tat with Kim Jong-un.

We are only eight months into this presidency, and Trump has already shown himself more than willing to shake up his White House staff. If he is serious about principled realism—not this doubling down on the failed status quo of the last decade and a half—it may not be too late.

"To a very considerable extent, Trump defeated Hillary Clinton, preferred candidate of the establishment, because he advertised himself as just the guy disgruntled Americans could count on to drain [the Washington] swamp," notes military historian Ret. Col. Andrew Bacevich at The American Conservative. This is a project that must centrally include a serious rethink of U.S. foreign policy. If Trump is serious about making good on that promise, if he is "really intent on draining that swamp—if he genuinely seeks to 'Make America Great Again'—then he would extricate the United States from war."

The first step in that long journey would be getting input from advisers who agree.

Show Comments (15)