From Nazi Propaganda to the Pee Dossier, FARA Targets Alien Influence on U.S. Politics

Here's what you need to know about the Foreign Agents Registration Act, an obscure ethics rule that could tar both the Trump campaign and the firm hired to bring it down.

A relatively obscure federal disclosure law, the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), is having a moment in the spotlight, thanks to scrutiny of the Trump campaign's potential ties to Russian agents.

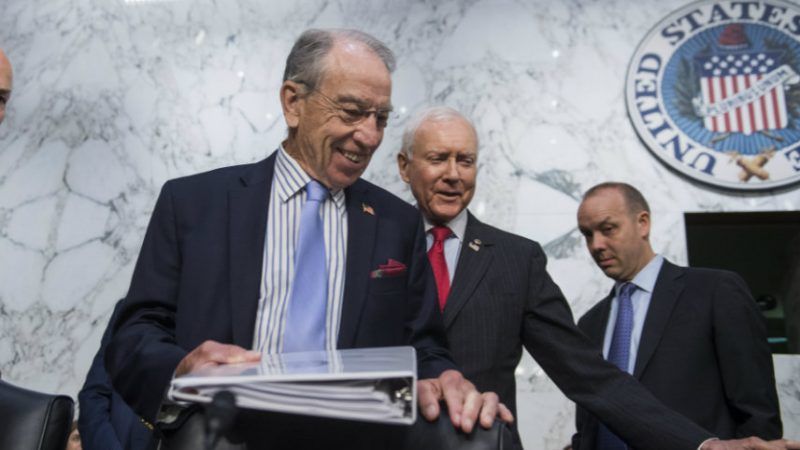

"Given recent Russian and other efforts to influence our elections, this law has never been more important," asserted Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) Wednesday on Capitol Hill.

Here's what you need to know about why the law is important and how the government goes about enforcing it.

Why FARA Is in the News Now

On Thursday, William Browder, CEO of Hermitage Capital Management, will testify before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary as part of its "Oversight of the Foreign Agents Registration Act and Attempts to Influence U.S. Elections." (Browder's written statements were published Wednesday.)

Browder last year filed a complaint with DOJ alleging that unregistered individuals were working on behalf of the Russian government to have something called the Magnitsky Act repealed.

Congress passed the Magnitsky Act, which gives the U.S. greater power to sanction Russia over human rights abuses, in 2012 in reaction to Russia's treatment of Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky and Browder.

Browder has alleged Fusion GPS—the firm behind the Trump-Russia Dossier–was hired by Russians to work to repeal the Act. Fusion allegedly brokered the infamous June 2016 meeting with Donald Trump Jr., Jared Kushner, former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort, and Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya.

Donald Trump Jr. later admitted the meeting was brokered for the Russians to provide the Trump campaign with dirt on Hillary Clinton. Instead the meeting allegedly involved the Magnitsky sanctions.

Browder also alleges other lobbying firms were hired to promote a documentary tarring Magnitsky and him, but "at no time did they indicate that they were acting on behalf of Russian government interests nor did they file disclosures under [FARA]."

The Judiciary Committee had subpoenaed Fusion founder Glenn Simpson, but committee chairman Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) withdrew it after Simpson agreed to a private transcribed interview about his involvement in creating the dossier, his interactions with the FBI, and his alleged work for the Russians who met with Trump Jr. and company.

Fusion and Simpson were also accused by activist Thor Halvorssen in his Senate testimony of having worked for companies in Venezuela to influence U.S. media coverage.

The committee is still in negotiations to get Manafort's cooperation. Manafort is under fire for his role in the Veselnitskaya fiasco and belatedly filing FARA paperwork for consulting he did for a pro-Russia political party in Ukraine.

FARA was also a subject of discussion with regard to former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn. As Just Security notes, Flynn "belatedly registered under the statute after it was discovered that his lobbying firm received $530,000 for work on behalf of a Dutch company with ties to the Turkish government."

On Wednesday the committee also took testimoney from Grassley, U.S. Inspector General Michael Horowitz, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Adam Hickey, and Assistant Director of the FBI Counterintelligence Division Bill Priestap.

FARA Basics

Enacted in 1938 to deal with communist and Nazi propaganda, the Foreign Agents Registration Act exists "to insure that the U.S. Government and the people of the United States are informed of the source of information (propaganda) and the identity of persons attempting to influence U.S. public opinion, policy, and laws," according to the Department of Justice (DOJ).

FARA requires people and entities acting "as an agent of a foreign principal" in an attempt to influence U.S. politics to register with the office of the U.S. Attorney General and disclose detailed information about their activity. The law defines foreign principal to include not just foreign governments and political parties but any person who is not a U.S. citizen or entity operating under U.S. laws.

In addition, "an agent must file with the Department of Justice any informational materials distributed on the behalf of the foreign principal to two or more persons in the United States within 48 hours of distribution. The information materials must include a conspicuous statement that additional information is on file with the Department of Justice."

"FARA is a procedural statute, not a substantive one," notes Steve Vladeck at Just Security. It "does not prohibit particular activities in the abstract; it merely requires that those engaged in such activities on behalf of foreign interests identify themselves (and disclose their interests) to the U.S. government."

(Separate laws forbid public officials from acting as agent of foreign principals and "information gathering and other espionage-like activities on behalf of a foreign government," according to Horowitz. "FARA is focused on requiring registration and disclosures by foreign agents engaged in legal activities, such as lobbying, tourism, and economic development.")

There are sensible exemptions to FARA provisions. You don't have to register with the federal government when doing private and nonpolitical trade activities with a foreign entity, or soliciting contributions for humanitarian purposes.

There are exemptions for U.S. diplomats, the press, most lawyers representing foreign clients, and anyone engaging in "activities in furtherance of bona fide religious, scholastic, academic, or scientific pursuits or of the fine arts."

People are also exempt from FARA requirements "if they're allowed to register under other lobbying statutes," Vladeck writes. Those working for foreign commercial, rather than political, interests may register under the 1995 Lobbying Disclosure Act, which has fewer and easier-to-satisfy requirements.

FARA Registrants

As of today, there are 398 active primary registrants in the FARA directory. You can check out all active registrants by client country here.

FARA History and Enforcement

FARA is enforced by a unit within the DOJ's National Security Division. Violations are punishable by up to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. But "the cornerstone of the Registration Unit's enforcement efforts is encouraging voluntary compliance," according to a manual from the U.S. Attorney's Office (USAO).

Failure to register must be intentional or the information registered must be be false or willfully deceptive to be a criminal act. Without evidence of intent, federal authorities will first send a letter "advising the person of the existence of FARA and the possible obligations thereunder," the USAO explains.

From the time of its passage, FARA was focused on the spread of propaganda. Amendments in 1966 shifted its focus to the role of foreign influence in America politics via back-channel money and influence.

Notably, this shift coincided with around a 100 percent decrease in successful prosecutions. Since 1966, DOJ has no criminal convictions under FARA and only three indictments have been returned, according to the U.S. Attorney's Office. (This number conflicts with the figures provided to the Senate committee by Grassley, Horowitz, and Hickey, whose figures also all conflict with each other's. However, no one alleges more than four criminal convictions since 1966.)

A 2014 study from the Project On Government Oversight (POGO) found "a pattern of lax enforcement" of FARA requirements, and that the "office responsible for administering the law is a record-keeping mess."

The group also discovered that "while federal law bars foreign money in U.S. political campaigns, there appears to be a gray area allowing such funding indirectly. POGO found many instances of lobbyists making political contributions to members of Congress on the same day they were lobbying the members of Congress or their legislative staffs on behalf of foreign clients."

A 2016 audit from the U.S. Inspector General's Office found that 42 percent of initial FARA registrations were late, and half of registrants were late in filing at least one supplemental statement.

The audit also "found that there is a fundamental disagreement among government officials about what constitutes a FARA case," Grassley said Wednesday. "No organization can properly enforce the law when it is confused about what the law is."

According to IG Horowitz, DOJ authorities blamed their low activity in part on "difficulty compelling the production of information from persons who may be agents," and in response request the authority to lobby civil investigative demands on suspects.

"While we agreed during our audit that this authority could be a useful tool for [federal investigators], there are important competing considerations at stake," said Horowitz, "and we believe that any expansion of such authority must also include controls and oversight to ensure it is used appropriately."

Looking Forward

From a libertarian perspective it is unclear whether increased enforcement of FARA will be good or bad. To the extent that a pledge of renewed commitment actually targets government corruption and strives for increased transparency, we will benefit.

But if history is our guide, people in power only get gung-ho about FARA enforcement when they can use it to target political enemies or stoke public fear of foreign menaces that benefits a preferred foreign-policy agenda.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Countries engage in skullduggerous shenanigans at other countries; film at 11.

Enacted in 1938 to deal with communist and Nazi propaganda, the Foreign Agents Registration Act exists "to insure that the U.S. Government and the people of the United States are informed of the source of information (propaganda) and the identity of persons attempting to influence U.S. public opinion, policy, and laws," according to the Department of Justice (DOJ).

Then all of Hollyweird needs to register because of the commie crap they feed our children and the more weakminded Americans. Am I right, people?

Especially that commie emoji movie.

Exemptions for State Department, press, Lawyers of foreign clients, academe, fine arts (Hollywood).

So the major organs of Leftist power, and particularly their propaganda power, are exempt. Why am I not suprised?

If we only had an unbiased media that was looking to inform Americans and make money to keep us abreast of propaganda and money influencing politics.

Speaking of dubious, shady foreign agents, you've got to love how most of the so-called "mainstream" media is desperately trying to ignore the story of this Imran Awan character who just got arrested trying to flee his way back to Pakistan.

And there were smashed hard drives in his garage. And DWS is on video threatening DC police for trying to access information in her laptop. And even after all this she just fired him yesterday. And his family members have gotten millions of dollars for part-time IT work, much of which has been sent back to Pakistan.

A guy at the Daily Caller has actually been doing some straight investigative journalism without any stupid Breitbart-esque BS. Most Democrat scandals are discovered by non-mainstream outlets.

Lewinsky? A tiny unknown website called Drudge Report.

Gruber tapes, where he blatantly says they lied and relied on the stupidity of the American voter to pass Obamacare? Some random guy.

The John Edwards scandal, where he was paying off his mistress/baby momma whom he had an affair with while his wife was dying of cancer, was broken by the fucking National Enquirer.

The Clinton/Lynch tarmac meeting? Some local reporter who just happened to be there.

It's almost as if our national media isn't interested in investigating Democrat corruption and scandal.

Leland Yee was one of the most influential California Democrats and a vocal gun control advocate. He was then arrested for arms dealing a few years ago. Barely made a blip on the news. The day after, CNN's front page had a story about some random state legislator in Arkansas who got a DUI, and nothing about the arms-dealing Democrat from California.

But the mainstream media are unbiased ethical "journalists" not propaganda factories of the left.

The most buried story in America!

This guy is a Democratic Party nightmare when his story becomes public.

Fist of Ineptitude should go to DC and help our cucklords crack down hard on Hollyweird! Please get involved! Smrt peopel like you are needed!

You misspelled Tronald Dump.

Setting the government as watchdog is fraught with the usual peril of a monopolist picking and choosing without accountability. If a private company had such rules, I would have no problem. It seems eminently sensible to require some truth in propaganda, so to speak. But to give the government this pick-and-choose power is just the usual dumbness.

FTFY

In reality there should be no disclosure laws for anyone and if any particular group is allowed to talk to any foreign national then all can since per the constitution all laws are to be enforced equally . I think someone could argue the laws unconstitutionality. but since when do people of either party care about that old piece of paper

So my understanding of FARA is that it not illegal to talk to foreign national but they, the foreign national have to be registered?

Do we really have to call it "the Pee Dossier"? Is "PissGate" not good enough for you media people all of a sudden?

The Magnitsky Act of 2012 was the first salvo in Cold War 2.0 against Russia. Sergei Magnitsky was an accountant who Bob Browder, a billionaire hedge fund manager, claimed was murdered by Russia after his wrongful conviction in a Russian prison because he revealed the Russian government and the Russian mafia conspired to rip off Browder for 230 million dollars. He lobbied Congress for the sanctions. This was two years before the Ukraine exploded.

Then Browder hired a European documentary filmaker to make a film about the affair. It turns out the filmaker realized half way through that Browder was lying. He concluded that Magnitsky was guilty of all charges, and that he was not murdered, but died of a heart condition, at most medical neglect in prison. Browder has appeared on all the left wing cable news shows last few weeks. He has used his considerable fortune to repress the documentary. The Russian Lawyer involved in meeting Donald Trump was lobbying Congress to see the documentary. No one would, so she screened it in a news museum next to the capitol. This is the only public screening of the film in English, as Browder has succeeded in having it blocked even in Europe. the only version is a Russian language version on You Tube.

I guess that might be a reason to hide everything from the rest of us!

Democrats are right: billionaires are corrupting US politics with their money, power, and influence. Browder seems like a prime example of that.

Other interesting notes: The adoption issue in the Trump meeting was due to Russia countered the Magnitsky sanctions by restricting US adoptions of Russian Children.

I apologize the correct name is William, not Bob Browder.

He is the grandson of Earl Browder, the former head of the Communist Party USA in the 1930's and up to 1945 when Stalin deposed him. Browder is extremely anti Russian and of course anti Putin.

Additional comment- We should require AIPAAC and other Israel lobbying fronts to register as Foreign Agents. They have surely been involved in more election interference than Russia or any one else

Yeah, and he is using the US government and his power and fortune for a personal vendetta, American interests be damned.

Just more examples of how our mainstream media will swallow a camel and choke on a gnat.

But donating millions to the Clinton Foundation doesn't count, right? A billion here, a billion there, pretty soon we'll be talking real money. But she was Secretary of State for the Democrats. Wink, wink.

Exemptions for State Department, press, Lawyers of foreign clients, academe.

So the major organs of Leftist power, and particularly their propaganda power, are exempt. Why am I not suprised?

my Aunty Violet just got a new blue MINI Cooper Clubvan Wagon only from working part-time off a pc at home... see here now ????

Just think about this: Russia and other foreign countries abuse and kill many thousands of prisoners. But as a well-connected, wealthy prick, Browder manages to get a law passed just as payback because one of his friends was ill treated. And that law then plays havoc with US presidential politics, free speech, and US foreign relations.

The problem isn't Russia: we already know that Russia is an authoritarian shithole, and there is nothing we can do to change that. The problem is people like Browder corrupting US politics through money, power, and influence.

"it will be equally forgotten that the vigor of government is essential to the security of liberty; that, in the contemplation of a sound and well-informed judgment, their interest can never be separated; and that a dangerous ambition more often lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people than under the forbidden appearance of zeal for the firmness and efficiency of government. History will teach us that the former has been found a much more certain road to the introduction of despotism than the latter, and that of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants."

-Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist Papers

It it's true that history should guide us. In looking at the zeal and vigor of government it's absence is often as telling as it's application. We should not identify individual instances of failure and demand reversal but understand the underlying corruption it serves and craft policy with incentives to counteract the abuse of enforcement or lack thereof.

The constitutional question of unequal application of this law has created the ambiguity necessary for selective prosecution which has slipped entirely into non-enforcement and relegated it to a bureaucratic function easily manipulated but available for political shenanigans. This is the underlying corruption. This law and a hundred like it are how powerful insiders navigate the halls of power and how they can send outsiders to splinter upon the rocks. This is how the Clinton machine can appear so corrupt and remain untouchable collecting billions in "donations" smugly sitting before a congress that created the protections she enjoys. It further explains the wild veering of the current administration before and after election day who's every action seems to run afoul of some obscure old rule that the public has never heard of and even absent prosecution demonstrates that he is out of his depth.

very nice post. I like it. Thanks for sharing this information.

Tinder is the best online chatting application. Try it.

http://www.tinder-pc-download.com/ tinder for pc

http://www.tinder-pc-download.com/ tinder download