As Vaping Exploded Among Teenagers, Smoking Fell by Half

Defying its own data, the CDC continues to obscure the enormous harm-reducing potential of e-cigarettes.

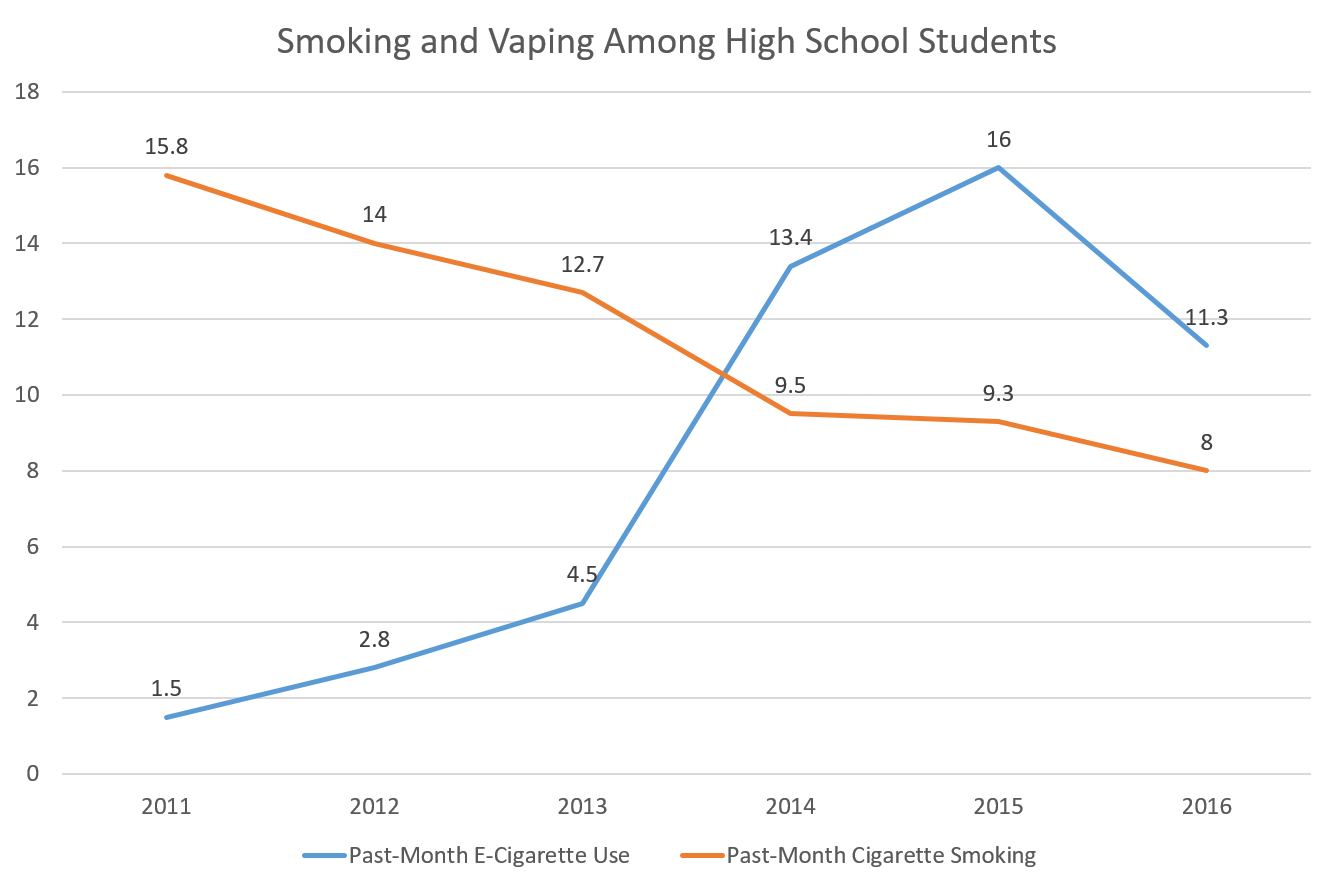

Survey data published last week cast further doubt on warnings that e-cigarettes are a gateway to the real thing for teenagers. Between 2011 and 2016, according to the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), the share of high school students who reported smoking cigarettes in the previous month fell from almost 16 percent to 8 percent, even as past-month use of e-cigarettes rose dramatically.

The incidence of past-month cigarette smoking among high school students in the NYTS, which is conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), fell from 9.3 percent to 8 percent last year, continuing a downward trend that began in the late 1990s. The incidence of past-month vaping, which rose steadily from 1.5 percent in 2011 to 16 percent in 2015, also fell last year, to 11 percent. From 2011 to 2016, in other words, e-cigarette use more than septupled, while cigarette smoking was cut in half.

"The rate of decline in youth smoking is unprecedented," writes Boston University public health professor Michael Siegel on his tobacco policy blog. "This despite the rapid rise in e-cigarette experimentation. These data are simply not consistent with the hypothesis that vaping is going to re-normalize smoking and that e-cigarettes are a gateway to youth smoking."

In theory, it is possible that adolescent smoking would have declined even faster if e-cigarettes had never been introduced. But on the face of it, these trends do not look like evidence that vaping entices teenagers who otherwise never would have tried tobacco into a nicotine habit that ultimately leads to smoking. Making that scenario even more unlikely, most nonsmoking teenagers who vape use nicotine-free e-liquids, and very few of them vape often enough to get hooked on nicotine in any case.

If anything, it looks like e-cigarettes have taken the place of the conventional kind for at least some teenagers who otherwise would be smoking. That is unambiguously an improvement from a public health perspective, since smoking is far more dangerous than vaping. Yet the CDC continues to talk as if there is little or no difference between smoking and vaping as far as health hazards go.

"Current use of any tobacco product did not change significantly during 2011–2016 among high or middle school students," says the article on the latest NYTS data in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. That is true only if you classify e-cigarettes, which contain no tobacco, as tobacco products, which they aren't. The report's authors concede that "combustible tobacco product use declined" during this period but obscure the significance of that development. "Use of tobacco products in any form is unsafe," they say, ignoring the enormous difference between combustible cigarettes and alternatives such as e-cigarettes, which are something like 95 percent safer.

By exaggerating the threat posed by adolescent experimentation with vaping (and experimentation is all it typically amounts to), the CDC hopes to justify policies that will make e-cigarettes less accessible and less appealing to adult smokers. "Sustained efforts to implement proven tobacco control policies and strategies are critical to preventing youth use of all tobacco products," say the authors of the NYTS report, citing the Food and Drug Administration's regulation of e-cigarettes as an example. But the FDA's rules threaten to cripple an industry that could help millions of smokers prolong their lives by switching to a far less hazardous source of nicotine. The CDC therefore is endangering public health when it rationalizes those regulations as sensible safeguards against adolescent vaping.

Show Comments (41)