We Could Have Had Cellphones Four Decades Earlier

Thanks for nothing, Federal Communications Commission.

The basic idea of the cellphone was introduced to the public in 1945—not in Popular Mechanics or Science, but in the down-home Saturday Evening Post. Millions of citizens would soon be using "handie-talkies," declared J.K. Jett, the head of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Licenses would have to be issued, but that process "won't be difficult." The revolutionary technology, Jett promised in the story, would be formulated within months.

But permission to deploy it would not. The government would not allocate spectrum to realize the engineers' vision of "cellular radio" until 1982, and licenses authorizing the service would not be fully distributed for another seven years. That's one heck of a bureaucratic delay.

Primitive Phones and Spectrum-Hoarding Before there were cellphones, there was the mobile telephone service, or MTS. Launched in 1946, this technology required unwieldy and expensive equipment—the transceiver could fill the trunk of a sedan—and its networks faced tight capacity constraints. In the beginning, the largest MTS markets had no more than 44 channels. As late as 1976, Bell System's mobile network in New York could host just 545 subscribers. Even at sky-high prices, there were long waiting lists for subscriptions.

Cellular networks were an ingenious way to expand service dramatically. A given market would be split into cells with a base station in each. These stations, often located on towers to improve line-of-sight with mobile phone users, were able both to receive wireless signals and to transmit them. The base stations were themselves linked together, generally by wires, and connected to networks delivering plain old telephone service.

The advantages of this architecture were profound. Mobile radios could use less power, because they needed only to reach the nearest base station, not a mobile phone across town. Not only did this save battery life, but transmissions stayed local, leaving other cells quiet. A connection in one cell would be passed to an adjacent cell and then the next as the mobile user moved through space. The added capacity came from reusing frequencies, cell to cell. And cells could be "split," yielding yet more capacity. In an MTS system, each conversation required a channel covering the entire market; only a few hundred conversations could happen at once. A cellular system could create thousands of small cells and support hundreds of thousands of simultaneous conversations.

When AT&T wanted to start developing cellular in 1947, the FCC rejected the idea, believing that spectrum could be best used by other services that were not "in the nature of convenience or luxury." This view—that this would be a niche service for a tiny user base—persisted well into the 1980s. "Land mobile," the generic category that covered cellular, was far down on the FCC's list of priorities. In 1949, it was assigned just 4.7 percent of the spectrum in the relevant range. Broadcast TV was allotted 59.2 percent, and government uses got one-quarter.

Television broadcasting had become the FCC's mission, and land mobile was a lark. Yet Americans could have enjoyed all the broadcasts they would watch in, say, 1960 and had cellular phone service too. Instead, TV was allocated far more bandwidth than it ever used, with enormous deserts of vacant television assignments—a vast wasteland, if you will—blocking mobile wireless for more than a generation.

How empty was this spectrum? Across America's 210 television markets, the 81 channels originally allocated to TV created some 17,010 slots for stations. From this, the FCC planned in 1952 to authorize 2,002 TV stations. By 1962, just 603 were broadcasting in the United States. Yet broadcasters vigorously defended the idle bandwidth. When mobile telephone advocates tried to gain access to the lightly used ultra-high frequency (UHF) band, the broadcasters deluged the commission, arguing ferociously and relentlessly that mobile telephone service was an inefficient use of spectrum.

It may seem surprising that they were so determined to preserve those vacant frequencies. Given that commercial TV station licenses were severely limited—enough to support only three national networks—they might have seen the scores of unused channels as a threat. What if policy makers got serious about increasing competition? Shrinking the TV band by slicing off chunks for mobile phone services could have protected incumbent broadcasters from future television competitors. Why, then, did they oppose it?

The answer: The broadcasters believed they held sufficient veto power to prevent the prospect of competing stations. Meanwhile, they cherished the option value of unused spectrum. This thinking proved prescient: Years later, unoccupied TV frequencies would be awarded to the incumbent broadcasters, without payment, during the transition to digital television.

A Recipe for Delay Meanwhile, MTS was being supplied by licensees called radio common carriers (RCCs). The government's policy was to license just two mobile operators per market, generally AT&T and a much smaller competitor. The FCC also distributed "private land mobile" licenses to companies not in the communications business, for strictly internal wireless use. These allowed, for instance, an airline to coordinate baggage operations at an airport, a freight train to check its track assignments, or workers on an offshore oil rig to talk with company personnel at the home office.

In 1968, there were 62,000 common carrier phone subscribers, almost equally split between AT&T and, collectively, 500 tiny rivals. Private land mobile licenses were allotted far more bandwidth (about 90 percent of the spectrum set aside for land mobile) and deployed more phones. But compared with the 326 million U.S. cellular subscriptions that existed by 2012, both of these low-tech services were fleas on an elephant.

The RCCs intensely opposed cellular, rightly fearing that it would ravage their small-scale, barely profitable operations. They had a powerful ally in Motorola, then a pioneering wireless technology company. Both the RCCs and the private land mobile operators were excellent Motorola customers, buying radios that cost thousands of dollars each. Motorola's major rival, AT&T, was excluded from selling land mobile radios by a 1956 antitrust settlement. Protecting its dominant market position meant protecting its customers from competition, so Motorola worked to deter the cellphone revolution.

AT&T's Bell Labs had conceived and developed cellular technology. But as passionate as its scientists were about mobile phones, the company enjoyed lucrative monopoly franchises in fixed-line telephony. AT&T convinced itself that mobile services would not add much to corporate sales, so it was much less aggressive in pushing for the new tech than it might have been. That allowed anti-cellular interests to have their way with regulators for many years: While AT&T formally requested a cellular allocation in 1958, the FCC did not respond until 1968.

In 1970, the agency finally agreed to deploy some spectrum for the new service. It proposed to make room by moving the television stations at channels 70 through 83 to lower assignments, and it cobbled together some other idle frequencies as well. But the issue was far from settled. From 1970 until 1982, cellular technology would be caught in a vortex of legal chaos, battered by rulemakings and reconsiderations and court verdicts. A 1991 study published by the National Economic Research Associates concluded that, "had the FCC proceeded directly to licensing from its 1970 allocation decision, cellular licenses could have been granted as early as 1972 and systems could have been operational in 1973." But a lot of businesses had an interest in keeping the FCC bottled up.

It was a Motorola vice president, Marty Cooper, who placed the first cellular call with a mobile handset in 1973. It might as well have been a pocket-dial. Motorola's lawyers were placing calls of their own, lobbying FCC bureaucrats to keep cellular networks from being built. (Motorola misjudged its own interests: It would become a leading beneficiary of the new marketplace. By 2006 it was the world's second-largest vendor of cellphones, selling more than 200 million units per year.)

Even in moving forward, the FCC clung to old prejudices. The commission deemed cellular a natural monopoly, so "technically complex [and] expensive" that "competing cellular systems would not be feasible in the same area." Not only did it see no scope for competition, but it felt there was no chance that any company other than AT&T could possess the skills or infrastructure to provide the service. Ma Bell was thus the only cellular operator authorized in the FCC's original plan. The commission didn't abandon that monopolistic approach until 1981, when it belatedly recognized that "regulatory policies and technology had changed dramatically" over the previous decade.

In 1982, the FCC finally started accepting applications for cellular licenses. Its plan called for 734 franchise areas, or two per market. One would go to a local phone carrier, typically a Baby Bell. (AT&T was being divested at this time, with the local exchange carriers—"Baby Bells"—split off while AT&T retained its long-distance and equipment manufacturing businesses.) A "non wireline" company, not a Baby Bell, would receive the other license. Many needless limitations remained, but the technology was finally sneaking out to the public.

Four Decades in the Womb The FCC was not staffed by incompetents or slackers. It just didn't have mechanisms to match the problem. Its central planners had little ability to grasp, let alone balance, the intricate options they faced; to guess how science would develop; to anticipate what products innovators might deliver or what business models competitive forces might create; to predict how consumers would respond to any of this. Regulators were at the mercy of vested interests: They might consider a given approach "best" after the AT&T presentation, only to spin in favor of Motorola a month later. Nonetheless, the FCC reflexively tried to control each aspect of cellular.

The wizards in the private sector were not all-seeing either. In 1980, AT&T asked the respected management consultant McKinsey and Co. to estimate how big a market cellular might become. McKinsey forecast that 900,000 cellphones would be in operation by 2000. This was off by more than two orders of magnitude: The actual figure exceeded 109 million.

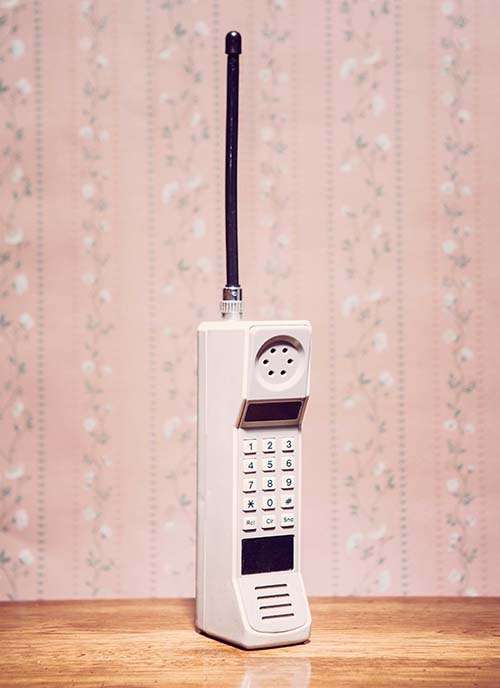

Nobody was omniscient, yet the spectrum allocation system was leveraged on the assumption of perfect foresight. Harsh realities stalled progress, allowing a parade of pleaders to thwart the future. Technology incumbents, TV broadcasters, radio common carriers, and anyone else who wanted to block competition (or make a sweet deal for an inside spot in the emerging market) used all the tools available to them to drag out the process even longer. A child conceived at the same time as cellular would have been 37 years old by the time the first commercial cellphone—Gordon Gecko's $3,995 Motorola DynaTAC 8000X brick—was released onto the market.

Once the blockage was cleared, progress popped. Soon, the science fiction vision of the Star Trek communicator was reality. Who knows what will happen if policy makers release the vast swathes of radio spectrum still trapped in the rule-limited silos of yesteryear?

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "We Could Have Had Cellphones Four Decades Earlier."

Show Comments (123)