Seasteading in Paradise

New promise for floating free communities in a Polynesian lagoon—but is the movement leaving libertarianism behind?

For nearly a decade, the Seasteading Institute has been working to create autonomous floating communities on the ocean, where settlers can make their own rules de novo, unbound by the principalities and powers based on land. Founded by Google software engineer Patri Friedman—grandson of the libertarian economist Milton Friedman and son of the anarchist legal theorist and economist David Friedman—it has weathered its share of thin years, previously dwindling to a two-staffer, no-office operation. But on January 13 in San Francisco's Infinity Club Lounge, institute chief Randolph Hencken signed a memorandum of understanding with a new partner, one Jean-Christophe Bouissou**, and put the construction of an actual seastead onto the cusp of reality.

See also: 'To Live and Let Live' - The micronation of Liberland turns 2

Bouissou is no buccaneer or eccentric billionaire. He is minister of housing for French Polynesia, a collection of 118 islands and atolls in the South Pacific, technically an "overseas collectivity" of France. Seasteading will not begin on the government-free open seas after all. If Hencken, Bouissou, and their respective colleagues have their way, the first seastead will float next year in a lagoon within French Polynesian waters.

As Hencken prepared to sign the agreement, he declared that this shift from a freewheeling vision of a libertarian society in the open ocean to a more tightly managed experiment in an existing nation's territory was probably inevitable. "We are not turning our backs on who we are," he said just before the ceremony, "but we are recognizing that when we made the choice in 2012 that we weren't going to the open ocean—we didn't have a billion dollars to build a floating city—that we'd have to engage in the politics of nations. It's challenging, but that's the reality of the human world, right?"

French Polynesian President Edouard Fritch was supposed to be there, but he had to stay behind to tend to some minor upheaval in his cabinet. (Bouissou informed the audience that he got on the plane in Tahiti as minister of tourism but landed in California as minister of housing.) But none of this was a big deal, Fritch assured the crowd via Skype. Bouissou was there representing the government's intention that seasteading will happen in French Polynesia.

The agreement commits the parties to "studies addressing the technical and legal feasibility of the project in French Polynesia" and to preparing a "special governing framework allowing the creation of the Floating Island Project located in an innovative special economic zone." Since the Seasteading Institute is an educational nonprofit, the signing ceremony was also the public debut of a for-profit spinoff called Blue Frontiers, which intends to build, develop, and manage the first Polynesian seastead.

Considering all that can go wrong when trying to craft a bold plan to save the planet from its political, economic, and environmental troubles, the path to the agreement was surprisingly short and untroubled.

The Polynesian Fixer Marc Collins is kind of a big deal. Around Tahiti and its sister islands, he knows people who know people, and he knows all the people they know.

A former Silicon Valley resident himself, Collins grew up in Mexico and made his bones in French Polynesia as a retail jewelry king and an internet service provider telecom magnate. He also worked in the Polynesian government for two years as minister of tourism**. He claims to have once been the only person on the islands with a paper subscription to Wired magazine. So Collins was hip to the scene that produced the seasteaders—he'd been reading about them since 2008.

He noticed a 2015 article on Wired's website that said the seasteaders were ready to downsize their vision from a deep-sea project to a "floating city" in shallow offshore water. As a result, they'd need to collaborate with a host nation. So Collins contacted Hencken via LinkedIn and began cultivating relationships with him and other seasteaders via Skype and other means.

French Polynesia was exactly what they were looking for, Collins insisted. There weren't many cyclones; there'd been no tsunamis in a century; they had protected lagoons; and, all-important for a crowd of Bay Area techies, they had underwater fiber connectivity.

That first contact was in May 2016. The deal flowed fast. Collins set up a series of meetings with mayors, ministers, presidents, infrastructure builders, marine scientists, and businessmen, and he invited a crew of nine seasteaders to come on over, at the travelers' own expense, for what became a 10-day visit.

Making time for the trip was hard. It was in early September, right after the annual Burning Man desert art festival, which is a major event in the lives of a lot of high-level seasteaders. But they made the schlep from playa to paradise, even though direct flights to Tahiti from the San Francisco Bay Area don't exist—something Joe Quirk, the Seasteading Institute's communications director, says he hopes this project will change. (The Polynesians might hope that as well. Among their delegation at that Infinity Club signing was Michel Monvoisin, president of the major French Polynesian airline.)

The seasteaders were blown away by what they found—physically, socially, and politically. "In my 10 days I didn't meet a single Polynesian who didn't like the idea," Quirk says. And "the politicians were immediately and spontaneously speaking publicly about this. They weren't waiting for consensus, weren't asking for someone else to prepare a statement. They were right away publicly saying this was a good thing."

The visitors swam with friendly sharks, ate delicious meals of fresh raw fish in coconut milk on tiny motu, were hugged with familiar warmth by the mayor of Uturoa on the island of Ra'iatea, and presented their case to President Fritch and several ministers.

Tom W. Bell was there as the seasteaders' legal guru. (A law professor at Chapman University, Bell has effectively cornered the market in legal advice for the startup-city crowd.) In a forthcoming Cambridge University Press book, Your Next Government? From the Nation State to Stateless Nations, Bell writes that they spent their time "bouncing from paradise to paradise on planes, ferries, and fishing boats," contemplating how seasteads might provide needed cooling via shade to bleached-out coral.

Quirk speaks for all of the visitors when he says French Polynesia is "a place where you can't look anywhere and not think, 'I can't believe how beautiful this is.' Any random view in any direction would make an amazing screen saver." But as wonderful as the natural environment was, the sociopolitical environment seemed to be just as good. With Collins' guidance, Quirk says, they were shown "sites where we could float these things. Our engineer could dive to inspect the corals. We saw different buildings we could reside in and different businesses that could be involved." By the end of the trip, he was telling Collins that the fixer had undersold what a fit the place was for the project.

Greg Delaune was the latest addition to the seasteading team, having met Hencken face-to-face for the first time only the week before at Burning Man. Delaune, who runs an economic development consulting firm for cities called UIX Global, has a lot of experience dealing with governments at all levels. He says he was "excited by what I think is the genuine honesty, integrity, and transparency that the officials we dealt with showed. From my previous experience, that is a very pleasant surprise."

"The Polynesians are the original Seasteaders," adds Quirk. "They have a culture of getting on those Polynesian canoes and going to a new island and founding a new society. We go to them and talk about autonomy and choice and they love it, they get it, they get the idea of exploring and discovering new things. They were doing this 1,000 years ago."

Polynesia doesn't deliver everything for modern urbanites used to Silicon Valley or San Francisco. "There's no Amazon Prime," Hencken says. But there are real cities with populations in five figures—who have, the seasteaders hope, a willingness to allow them to experiment with new rules and new technologies.

The Polynesians are also already familiar with the concept of a space of limited autonomy carved out from within a larger legal entity, points out Monty Kosma, a former McKinsey consultant now with Blue Frontiers. A prospective seastead's relationship to French Polynesia is easily analogized to French Polynesia's with France.

More Aquapreneurs, Fewer Libertarians For Delaune, libertarianism is a "curious historical component" of seasteading. "I see the focus of this as on the technology and social experience," he says. "When I describe the elephant of seasteading, the libertarian thing is not part of it."

This revised vision is reflected in the new book Seasteading: How Ocean Cities Will Change the World (Free Press), written by Quirk with Friedman. (The latter is still on the Seasteading Institute's board of directors, though he is no longer actively working on its projects.) Competitive governance, the original heart of seasteading, is in the book. But it doesn't get extended attention until page 183 of the 346-page text.

It was changed circumstances, not a change in core ideology, that produced this shift. "After several years of research we concluded this is doable," Quirk explains. "But the jump to the high seas is too expensive. It's asking investors to take too big a risk." The institute does still stress that host governments will have to cede some legal and regulatory autonomy to the seasteaders. "If I just wanted to build floating infrastructure, I could do that in San Francisco Bay," Hencken says.

Still, Seasteading 3.0, as Hencken calls it, is energizing "aquapreneurs" with no links to the movement's libertarian roots. They include academics and entrepreneurs eager to use the ocean to solve food and carbon crises. (Seasteading 2.0 was a brief foray around 2012 into trying to start off with single-business operations on boats in non-territorial water.)

One is Ricardo Radulovich, a professor of water science at the University of Costa Rica who insists that the planet's health requires us to switch most of our food production to the water. He works through the Sea Gardens Project to demonstrate that a shift to seaweed cultivation can reduce carbon emissions, clean ocean dead zones, feed the world, and end coastal poverty. (Quirk and Friedman cheekily call seaweed "the best possible nanotechnology…self-assembling solar panels that are also edible.")

Radulovich told Quirk that he fears bureaucrats more than pirates or sharks. "We may need seasteads to move into international waters, where there are fewer regulations. We have to run to get ahead of regulatory burdens stopping us."

There are some bright spots. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is trying to reform itself, for instance, as Radulovich points out in an email. In its Marine Aquaculture Strategic Plan FY 2016–2020, the agency conceded that "regulation of U.S. commercial marine aquaculture is complex, involving multiple agencies, laws, regulations, and jurisdictions. As a result, permitting processes can be time-consuming and difficult to navigate, significantly limiting access to sites." But NOAA says it intends to make such processes easier moving forward.

Another aquapreneur introduced in the book is Neil Sims, an Australian marine biologist who mostly works in fishery management. He has developed a property-based "drifter cage"/"aquapods" approach to the task, which allows teams of two to raise tasty fish with no antibiotics while sending sequestrated carbon to the bottom of the sea as fish poop. NOAA studied one of Sims' aquapod projects and declared it would have no ill impact on the ocean. But Sims, like Radulovich, still faces regulatory barriers. "In the U.S., the regulatory framework is highly restrictive to the point of being dysfunctional," he told Quirk.

"There is no fish grown commercially in federal waters in the entire United States," Sims points out in an interview. "Why is that? Because the regulatory Gordian knot is impossible in most areas," including having to deal with NOAA, the Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, the Environmental Protection Agency, and coastal authorities from the nearest state. Even for his small experimental project near Hawaii, "to culture 2,000 fish at an experimental scale, it took us 24 months to get a permit to do that," and changing iterations of the project would keep requiring more two-year delays.

Another aquaculture company in the seasteaders' orbit—Catalina Sea Ranch, run by Phil Cruver—is succeeding in growing mussels in territorial waters off California; as Cruver explains it, the regulatory burdens for non-fish aquaculture are easier to navigate. Cruver, like Radulovich, thinks he sees signs that the federal government is interested in trying to make it a little easier for aquaculture to operate in U.S. waters.

While widening beyond the libertarian ghetto will be key to seasteading's future, Kosma guesses that anyone involved at this stage will likely have a "deep commitment either to the ideas it will serve in the world or just some deep belief in the individuals driving it forward."

The pressure of reality that has shifted the project from its more purely libertarian roots, Quirk says, "is that existing nation-states control all the shallow seas. So we need to go to coastal countries that have special economic zones already on the books" and sell seasteading.

"We don't even need your land," he adds. "Give us more regulatory autonomy in your sea zones, and we'll take the best practices of those 4,000 special economic zones around the world and apply them in your sea zone. And we'll bring our own land."

What's In It for Polynesia? The locals have their own reasons to want to grant that autonomy. One is the threat of global warming. Polynesians are naturally attracted to an idea that could let them stay where they are even as sea levels rise.

When Hencken and Bouissou signed their memorandum of understanding, Lelei Lelaulu attended as a representative of the Pacific Island Forum, a sort of mini-U.N. of Pacific island states. Lelaulu, a native Samoan, thinks seasteading has the potential to solve a looming problem for island sovereignties: losing the actual land over which they are sovereign. For such countries, he suggests, artificial floating islands will be a way to maintain their very legal existence. Kiribati is one Pacific island especially concerned about that.

The libertarian world that produced seasteading includes a fair number of climate-change skeptics, but Hencken isn't interested in debating sea-level changes with them. He merely notes that, whatever you believe about the phenomenon, they have clients who see it as a problem worth solving.

A second reason for the Polynesians' interest is jobs. The country has an unemployment rate of over 20 percent, and seasteading projects could be an important source of both employment and entrepreneurial opportunities.

A third reason is alternative energy. Nicolas Germineau, a French software engineer working with Blue Frontiers, notes that the islands face some of the same problems related to renewable energy generation and waste control that a seastead will have to solve. So "our sort of sustainable development is something they are very interested in."

Bouissou is also sure of some things he doesn't want to come of this. "We don't want to be like Hawaii," he told a workshop held the day after he signed the agreement with Hencken. "We want to keep our culture and languages and life as it's lived, authentic." (Tourism, a mainstay of the French Polynesian economy, took a huge dive around the turn of the century and is only slowly recovering.)

Collins thinks part of the Polynesian enthusiasm reflects the fact that the seasteaders did not come in asking for tax dollars or other financial support. All they want is the space and the freedom they need to make things work.

Everything about what might happen with seasteads is veiled in some necessary uncertainty as of press time. The seasteaders' current task is producing convincing economic and environmental impact reports that demonstrate to the Polynesians that a seastead will indeed be good for them. But ultimate approval has to come from more than just President Fritch and his already seasteading-friendly crew. The France/Polynesia relationship leaves the locals in charge of fiscal matters, but Paris still controls work visas and immigration—rather important issues for the seasteaders. An international law firm, DLA Piper, is helping the seastead group pro bono on the French angle, and Collins says the Polynesian government is dedicated to working out all necessary details with France.

Everyone involved wants what happens in French Polynesia to not stay in French Polynesia. Lelaulu suspects the Seychelles and Mauritius would quickly glom onto seasteading if it succeeds in the Pacific.

Perhaps because he's not an actual part of the dealmaking, Lelaulu was willing to spitball about possible sources of funding to build seasteads. "The Asian Development Bank is looking for things to do," he told the workshop held the day after the signing. "Look at sovereign funds. The Norwegian Pension Fund, they've always been keen on oceans, and they want to look good because they are still killing whales," he added. He also suggested playing the Norwegians and Swedes off against each other to squeeze funding for seasteading's ocean-saving possibilities.

So far, the actual seasteaders are either unwilling or unable to be specific about funding sources, though Quirk is open about the fact that they will need millions. A few weeks after the agreement was signed, he told me that "we have people in the mix definitely who are earnest about paying to see one built if they can get the type of regulatory and administrative autonomy they would require." But no one will name names.

Other presentations at the workshop seemed designed to impress the Polynesian delegation with the range of ideas, technologies, and people that made up the seasteading world. Most involved processes and projects that would make life on a seastead easier or more interesting: bio-gas production, smart grids, mobile clean waterships, wave energy conversion, nanotech building fibers, undersea robots. But they did not highlight any companies that would be willing to spend the big money to have a seastead built, which seems the most pressing problem facing the effort.

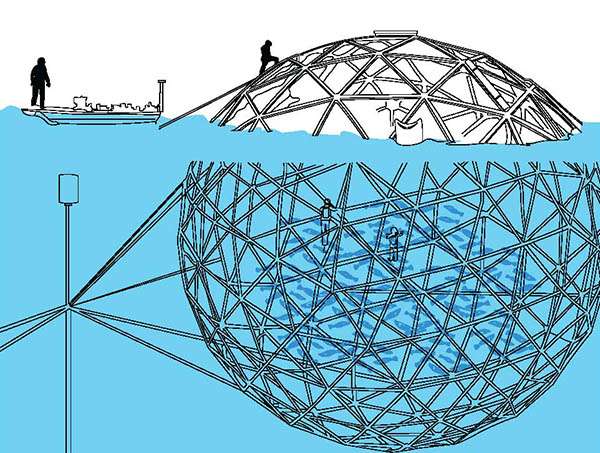

'If We Make It Beautiful, We Make It Bulletproof' Karina Czapiewska leads Blue Frontiers' physical design team. Her previous company, now known as Blue21, developed expertise in building floating municipal infrastructure in the Netherlands. (They "basically established the technology for totally sustainable floating platforms in shallow seas," Quirk says.) She is confident that no completely new inventions are needed to make a Polynesian seastead work. The problems have known solutions. It's just a matter of affordability.

It's also a matter of political feasibility. It's all sweetness and light right now between the seasteaders and the Polynesians. But as Bouissou said at the workshop, "We need to go into communities at the grassroots level and translate this technical knowledge into something the population will understand and will adapt and accept."

In December, before the seasteaders themselves went public with their agreement, The Guardian ran a story attacking the idea of Polynesian seasteads, quoting Tahitian TV host Alexandre Taliercio saying, "It reminds me of the innocent Ewoks of the moon of Endor who saw in the Galactic Empire a providential manna" but in fact were exploited. Quirk was grimly impressed that "they managed to find some guy who refers to his own neighbors as Ewoks" in order to take a swat at seasteading.

Chris Muglia, a former manager of a marine construction company, is the only Blue Frontiers leader with long-term experience on the water. Calling on his decades "working on almost every Caribbean island as well as the Marshall Islands," he says that islands have bitter experience with "people showing up and saying they have a great idea to do this and do that, then they disappear and never come back." He thinks a strong show of follow-through will go a long way in selling the islanders on the project.

The Polynesians are already familiar with the concept of a space of limited autonomy carved out of a larger legal entity, since that is French Polynesia's relationship with France.

What will the first seastead look like? All Czapiewska will say is that any articles grabbing random old designs from the internet and presenting them as "the seastead" are wrong. Muglia reports that "the first one will not be some big 14-story" thing, that there will of necessity be first steps and second steps as their methods become "cheaper and more sea-capable" and have "more capacity." Hencken dreams of a larger central structure amenable to that key aspect of seasteading, modularity, with smaller pieces able to attach to and leave the central base.

Nor is it clear what businesses or other activities will come to this structure. "It very much depends on what rules will be different," says Germineau. "Some business models are insensitive to lots of unknowns." He sees information tech, green tech, and ocean tech as likely first adopters.

Delaune of UIX Global thinks the conceptual and practical problem they'll have to solve—basically, creating a self-sufficient closed ecosystem—will create "high-value integrative technologies with potentially long-term revenue generation," something that in an age of eco-crisis and interplanetary exploration could be valuable even for people who couldn't care less about competitive governance. He also speculates that an early Polynesian seastead could be very attractive to "the global senior community." Or perhaps they could erect a global conference center for "seasteading-related ideas, technologies, and thought leadership."

Hencken expects the environmental and economic impact reports to be done in May. Muglia has been doing "initial surveys on different potential locations, looking at geotechnical stuff, what the bottom of different lagoons and bays" look like, and thinking about "anchoring [and other] super basic stuff," to pinpoint best and second-best spots for a build. Collins is confident that either Tahiti or Ra'iatea will be the host island for the first seastead. (Bora Bora has too much going on in its harbors.)

Whatever it ends up looking like, whatever its function, the first seastead needs "to make financial sense," Collins says. "We can't build a platform and devote half to a swimming pool or a soccer field. We don't want a dense urban environment either, and nobody on the team is talking about an enclave for rich tourists or just another way of doing a hotel on the water."

Bell, the lawyer, who has been a party to many failed or stillborn startup-city schemes, says working in this field can be "one heartbreak after another." His advice: "Don't fall in love with every project."

Still, the cheery optimism surrounding this Polynesian effort seems well-grounded. And Friedman insists that "the idea of competitive governance still overarches, or undergirds, what we see as the long-term 100-year impact" of the initiative. It's just that seasteading is a startup sector. If the only affordable way to begin involves a host nation, he says, then the parameters will be defined by "whatever makes the customer" want to buy in.

Even within those parameters, Quirk's vision of what they intend to accomplish is ambitious. "In 2017 we secure the legislation," he says. "In 2018 we start building floating islands in French Polynesia, and by the end of this decade I want the world to be looking at a floating island that makes them gasp and gives them a vision of the microcosm of freedom that is going to be on the sea, OK? It's got to be beautiful, it's got to look like nothing else in the world, it's got to be not just environmentally sustainable but environmentally restorative."

The biggest threat facing seasteading, Quirk says, "is political backlash. If we make it beautiful, we make it bulletproof. And our Floating Island Project is bigger than just this project. It is on the crest of a wave all over the world of 4,000 at least special economic zones. They have been proliferating and crowding up against the coast as if against a dam." If Quirk and his team have their way, the Polynesian project will bust that dam and flood the world with food, clean water, energy, and liberty.

**Bouissou's name was misspelled in an earlier version of this article. The length of Collins' service in the French Polynesian government was also misstated. The author regrets the errors.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Seasteading in Paradise."