Here's What It's Like To Be a Refugee

Refugees' full energies are devoted to earning money and absent family members overseas.

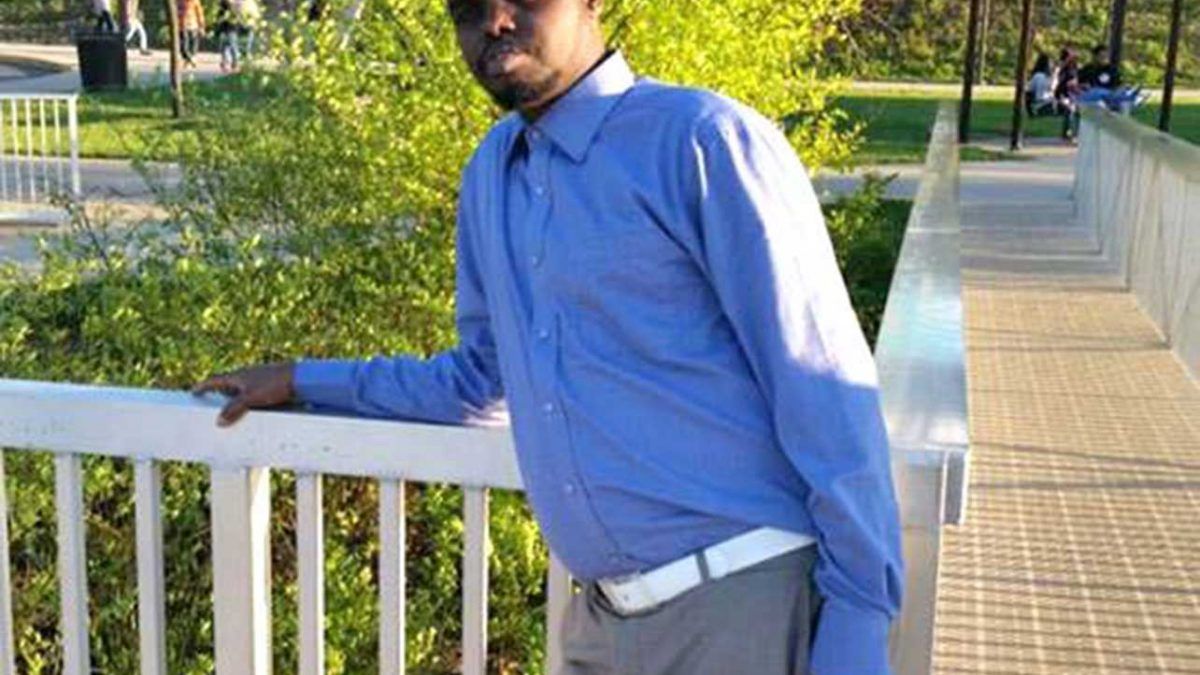

Every month in Louisville, Kentucky, Abdi Mohamed does a little bit of family banking.

The 32-year-old Somali man with dark, deep-set eyes and a cleanly trimmed goatee opens an app called Wave. Foremost in his mind are his wife, his 6-year-old stepdaughter, and his 3-year-old daughter. He tries to figure out how much money they need: Did they run out of toiletries? Any hospital visits? Have the girls grown out of their clothes? After running through his mental checklist, Mohamed determines a number, navigates the app, and taps his finger on the screen to send his family what they will need this month. The money withdraws from his bank account in Louisville. Eight thousand miles away in Nairobi, Kenya, Mohamed's wife Sophia gets a notification on her phone that the money has arrived from America.

"I send $500 to $600 per month to my family," says Mohamed, who earns $12.50 an hour working in an Amazon warehouse. "But sometimes there are medical bills; it fluctuates. So [I] may end up sending $500, $600, $700, and by the end of the month, [I] keep on sending other money. Sometimes it goes beyond $1,000." At these figures, he gives a helpless laugh.

Mohamed was 6 years old when he left Somalia, an arrow-shaped country capping the horn of Africa that has been hounded by civil war since a coup in 1991. His family fled across the border to Kenya and found tenuous safety in the refugee camp of Dadaab, and it was there that he grew up. After an unhappy first marriage, Mohamed applied for the United States Refugee Admissions Program, a yearslong process with the potential to result in resettlement to America. Then his plans went awry: He met Sophia, who had a daughter from her own previous unhappy marriage. She was beautiful, patient, and fastidious. The two fell in love and wed, and soon had a daughter of their own.

"Marriage and death are things that always come as a surprise," Mohamed says. "Sometimes things happen the way you don't plan it."

Since Sophia and the girls weren't a part of Mohamed's initial application, he was not able to add them to his case. In 2013, when he was approved for resettlement to the United States, he had to go alone. Now he's in the process of applying to bring them to join him in Kentucky. He works 60-hour weeks and sends them money to live on. Mohamed is keenly aware of the difference between himself and the other workers at his warehouse: They end long shifts and go home to their families, while his wife and daughters are an ocean away.

Mohamed is a legally "single" man who is simultaneously bound to support three dependents. His immigration attorney at Kentucky Refugee Ministries, Sarah Mills, calls his financial situation "maintaining two households," a phrase usually reserved for wealthy owners of multiple homes. Mills has been working with Mohamed since June 2014 to file a refugee family reunification petition, a legal channel through which refugees in their first two years in the United States can bring their immediate families to join them. But until his petition succeeds, Mohamed lives in a kind of limbo, his feet on Kentucky ground but his heart with his family in Kenya.

Thousands of such fragmented families exist. Just as most American families would not disunite intentionally, these refugee families never meant to get permanently separated. Under normal circumstances—their countries intact and safe, facing no persecution—they would function as single households living under the same roof.

Instead, many refugees' full energies are devoted to absent family members overseas. The cost of this separation, both to people like Mohamed and to the American communities they live in, demands closer investigation. So do the costly inefficiencies in the family reunification system.

'IF I MISS ONE DAY OF WORK, THEY WOULD SUFFER' Money is on the minds of most new refugees in the United States. The U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program aims for them to be financially self-sufficient within 90 days of arriving in the country. New arrivals learn that they must put aside any notions of full-time English classes in favor of finding a first job, and fast.

They are often blindsided by the cost of living in America. "There are so many bills: water, house, electricity," says Elhadi Adam, a Sudanese refugee who fled Sudan's ethnic cleansing campaign and resettled in Maryland in 2012. But even with these costs, Adam's life in America was still better than that of his family in a displacement camp in Sudan. "You have comfort here. Your family is there, and they don't have anything to eat. Here you have something to eat. So why save money? If you work two jobs and are a hard worker, you can pay your rent, and after that you can wire what's left to your family. So there is no sleep—if I miss one day of work, they would suffer." In the five years Adam was separated from his wife and their young son and daughter—they were reunited in 2015—he estimates that he sent them around $10,000 for living expenses.

According to the World Bank, immigrants living in the United States send more money abroad than immigrants in any other country, remitting approximately $56.3 billion in 2014. Refugees make up a tiny fraction of immigration to the United States, and there is no reliable way to track refugee-specific remittances, but globally, they are among the poorest and most disenfranchised groups on the planet. I spoke with dozens of fractured refugee families; the need to send money home proved persistent and all-consuming.

The form for a refugee to bring a spouse or child to the United States is only four pages, but submitted applications can run hundreds of pages long. Legal professionals like Mills become a necessity, because a key part of the application requires refugees to prove their relationships with the people they want to bring.

Immigration lawyers will often try to show financial dependency to demonstrate that a marriage is real. They collect receipts from money transfers, screenshots from money-wiring apps like Wave, and even affidavits from black-market wire transfers, all proving that their stateside client sends money to a spouse or child overseas. The mountains of evidence make legal professionals key witnesses to this flow of cash.

Attorney Heather Scavone, who runs the Elon Humanitarian Immigration Law Clinic in Greensboro, North Carolina, believes there is a strong economic argument for refugee families to be reunited as quickly as possible. "When you have a refugee making $8.50 an hour and their family is in the [Democratic Republic of Congo]," she says. "they're sending a substantial portion of their wages overseas to take care of their family." Instead of investing their paychecks in their new American communities, they send them to camps and slums in foreign countries. Instead of investing in their own life in the United States—purchasing homes, buying cars, frequenting American businesses—they are desperately scraping together every extra cent of their earnings to sustain a second household abroad.

'PENDING, PENDING, PENDING, PENDING' Moges Betru has spent three and a half years waiting for his wife, Sadada. He is an intense, slight man from Ethiopia who fell in love with Sadada via old-fashioned correspondence. His landlord was her uncle, and over the course of several years they started to spend more and more time chatting on the phone. "Whenever she called [her uncle], she talked to me, so we started to get to know each other and exchanging Facebook [messages] and letters. Later on, we started talking, and decided to marry each other." They wed in 2012.

Betru, like many refugees, did not want to jeopardize the resettlement process he started in 2010 by belatedly adding Sadada to his case. So he came alone to Greensboro in September 2013. Right away he began the process of applying for Sadada to join him, and he sought help from Church World Service.

His first petition was denied for reasons he doesn't know. In 2015, he moved to Louisville, and there he received help applying again, this time from Kentucky Refugee Ministries. Then the waiting began in earnest. As of February 2017, Betru had four words to say: "Pending, pending, pending, pending."

Refugee family reunification petitions such as Betru's start at the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), either in Texas or Nebraska, where an adjudicator reads the paper petition and determines whether someone in Betru's position has given enough evidence that his wife is really his wife. Petitions at USCIS "are generally approved pretty quickly," writes Rebecca Sim, attorney at Catholic Charities of Louisville. The USCIS office then sends the file to the National Visa Center (NVC) in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, which then sends it on to the U.S. embassy or consulate nearest to the family member abroad.

That is an ideal case. "More often than I am sure the government would like to admit, the file is lost in transit from USCIS to the NVC," Sim explains. "If the file is lucky enough to arrive at the NVC, it could become lost in transit from the NVC to the assigned U.S. embassy or overseas USCIS office. Lost files can result in extremely long delays."

Betru's lawyer in Louisville, Becca O'Neill, sent his application to the USCIS, but it never made its way onto the desk of an adjudicating officer. When O'Neill contacted USCIS, seven months after sending in Betru's petition, the office said it was never received. Betru was exasperated: "It took us like six months to appeal."

This time, Betru's application was approved, but another human error followed. The National Visa Center sent his file to the American Embassy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and asked Sadada to come in for an interview. This would have been the correct next step if Sadada lived in Ethiopia, but she lived and worked in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates. The mishap cost months; to reroute a file between embassies, even those only a four-hour plane ride apart, the file had to first go to the United States, then be sent out again to Dubai.

And these are minor gaffes compared to the bureaucratic satire that can play out once these petitions reach the State Department's embassies and consulates. A combination of local mood and institutionalized bureaucracy can drag out the application process for years.

Aside from a not-quite-consummated pilot program that attempted to streamline the family reunification process, most embassies or consulates complete their own adjudication on the petition USCIS has already adjudicated and approved. Consular staff might ask for additional proof of a real family relationship. This puts petitioners, or rather their lawyers, in a back-and-forth not with a USCIS office in Nebraska but with a U.S. embassy or consulate overseas.

Andrew Haile, a lawyer who published "The Scandal of Refugee Family Reunification" in the Boston College Law Journal in 2015, described files at an embassy as being in a "black hole." In my interviews across the board, immigration lawyers bemoaned this stage of the process. Embassies and consulates can vary widely in their communicativeness and efficiency when it comes to these visas, and refugee petitioners and their lawyers might go months without hearing from consular staff. Sim recalls an embassy where a file was "just placed to the side and forgotten," adding a year to the family's estrangement.

"It is like elastic," says Congolese refugee David Zihalirwa, who petitioned in 2015 for his wife and 1-year-old daughter to join him. "They say two months, then it becomes three months."

In November 2015, Moges Betru's wife Sadada finally completed her interview. Six months later, neither of them had heard any news. Now, in 2017, he says that he would never advise another person to go through this process. It's "killing you slowly," he says. "It doesn't kill you quickly. They tell you, 'Don't worry. You'll go, maybe soon.'" Sadada has still not been cleared to join Betru, and he is close to giving up.

EXECUTIVE ORDERS AND DELAYS Fixing that bureaucratic stagnation may become a moot point if refugee family reunification continues to get wrapped up into executive orders on immigration. President Donald Trump's January 27 temporary ban on arrivals included people holding V93s, the visa for refugee family reunification. The March 6 clarification lets those already holding this visa enter the country, but still delays or stymies family waiting in the USCIS or embassy stage of the reunification process.

Lags such as these can be costly. Each refugee coming to the United States, including those joining family members, must pass certain timed hurdles before boarding a plane to the United States. Medical examinations must happen within 90 days of departure, security clearances must be recent (clearance timing varies by country of origin), and the U.S. Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration must coordinate with the International Organization of Migration for plane tickets and itineraries.

This process can run like a well-oiled machine, but executive interference has rippling effects. Missing a medical clearance means waiting for another one, during which time the security clearance will likely lapse—and by the time the plane tickets are finally rebooked, the medical clearance may well lapse again. This cycle of lapsing can add up, both for the taxpayers and the family member waiting in the United States.

Immediate family members of refugees are considered "derivative" refugees, and fall under the refugee category of immigrant arrivals, whether or not they themselves qualify for refugee status. They therefore are among those who would be denied entry to the United States for 120 days under the March 6 executive order. It is unclear whether this order will ever go into effect, but if it does, Mohamed and Betru can expect a much longer wait for their wives.

BUDGET LIMBO The bulk of money that refugees send their immediate kin abroad goes to basic living expenses for family members in poverty. Money for food and rent top the list, followed by medical bills. In Chad, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported a 96 percent funding gap in 2016, "mainly in the domains" of food and firewood for refugee camps. Media fads can skew funding toward newer and trendier crises, such as the one in Syria. But even Syrian refugees in the same year were barely better off, with only 12 percent of their basic needs met.

Two families I spoke with reported children who died in camps of disease or malnutrition while they waited out the process of reunification. One man confided that his wife back in the camp had begun trading sex for food to feed their children.

A certain percentage of this money only makes it as far as the channels that carry it. Many Darfurian refugees reference a Sudanese man in Connecticut who informally transferred money to both Chad and Sudan. He apparently took a $5 fee for every $100 sent abroad, half the cost of legal wiring channels. Western Union's website estimates a fee of $12 for every $100 sent to Chad, and The Economist documented in 2014 that remittances sent to the African continent usually incur a 12 percent fee.

Travel, too, gets expensive. When it comes time to go to the "nearest" consulate or embassy for the final stage of a family member's processing, costs can skyrocket.

Bakit Adam, a Sudanese refugee resettled in Louisville, was baffled when he learned that his family had to make their way over 1,500 miles from the Gaga refugee camp in eastern Chad to Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, to continue their processing. The first $700 got his wife Fatima and their five children to the border, then the money ran out. Fatima recalls, "We called Bakit, and then he sent money. And then we finished the money, and then we called him. One time, two times, three times."

That was just to get the family to Yaoundé. Another $500 went to renting a house there. "Every 10 days, I was sending them $400 to $500 while they were in Cameroon. I didn't even go to school. I had to work every single day. No sleep!" His family waited in Yaoundé for seven months as the American Embassy processed their visas.

Apart from the expected bribes to border guards and policemen, some refugees must pay smugglers' fees to exit their native country or to help their family member cross a dangerous border. When host countries' police are hostile to refugees, bail money for jail stints can get rolled into the budget.

Additional costs come with proving a relationship to the embassy and consular staff. If the embassy or consulate decides to ask for DNA evidence to prove that a child is related to her parents, this can be expensive, especially for large families. Jacqueline Kasongo, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo in Lexington, paid $1,600 to complete DNA testing to reunite with her five children. It took six months to scrape together the money, but it proved that the children were hers and enabled her to move to the next step in the process.

WAITING FOR A BREADWINNER Many refugees in the United States find themselves in the reverse situation. Rather than having to earn extra money to support someone abroad, they are insolvent precisely because their families are incomplete.

"We get a lot of single moms who have spouses abroad," says attorney Emily Jones, Mills' colleague in Lexington. "It's hard enough to be fluent in English and be a single mom in the U.S., much less be here without the language capabilities or skills from the get-go. And to expect them to be self-sufficient in 90 days…is kind of an impossible task. So if we don't let them bring their husbands, we're setting them up to be dependent instead of self-sufficient."

Two such women I interviewed in October 2016 in Louisville, Maryama Omar and Endo Dega Muhumed, were disabled and unable to work. They were waiting for their husbands to arrive and bring income into the household. Omar was reunited with her husband at the end of 2016, but Muhumed, a Somali refugee with two children, still wonders when her husband will be allowed to join her.

Even for an able-bodied person, it can be stressful to be a single parent at the low-wage jobs open to people who are still learning English. Layla Makki, a Sudanese refugee, worries that her health may deteriorate due to her single-parent status. She imagines that if her husband were here, "I could just take some days off and rest. But I have to work. I have to work every day."

ASSIMILATING ALONE With so much energy spent worrying about family members abroad, what chance do refugees in America have to become productive, contributing members of their new communities?

On one hand, this is a simple issue of time. If a man such as Abdi Mohamed spends 60 hours a week working at his packing job, dead set on sending every extra cent he has to his wife and girls in Nairobi, and if he spends every additional hour possible taking ad hoc interpreting jobs, this leaves him without much time for anything else. Mohamed has strong English but plenty of refugees, such as Bakit Adam, do not. And while English classes are often free, refugees who spend all their time working cannot attend them.

The second barrier between Mohamed and his new American community is less tangible. Scavone, the Elon attorney, describes it as a palpable difference fragmented families in the United States feel between themselves and the people around them, "because every night you go to bed and your children are in harm's way." She cites this as a major barrier to integration.

The resettlement program intends for economic self-sufficiency to integrate refugees into their new communities. But economic self-sufficiency isn't enough when an immigrant's eyes are glued to places and people across the sea. "Keeping them from their immediate relatives makes it really hard to integrate or to feel like this is their home, their country that they need to be invested in," Jones says. "Because they're torn between two places."

When Abdi Mohamed speaks, he bangs his fist on the table for emphasis. "I haven't seen my kids in three years." Bang. "The waiting is the most stressful part." Bang.

Sometimes he toys with the idea of buying a plane ticket to see Sophia and the girls. He has the price of a travel document for refugees memorized: $240. He knows the plane ticket would cost a little over $1,000. He envisions getting his hands on this kind of money: credit cards, taking out loans, going into debt. The possibility is seductive.

"But if I were to go now, and give a child to my wife…" He drifts off, knowing the consequences of having another baby, a child who was not originally a part of his case. "The process starts over. Another three years." The risk is too high. So he goes to his 10-and-a-half-hour night shift, and puts in the work for his paycheck. Then he sends what he can to his wife.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Home Economics for Refugees."

Show Comments (91)