Why We Still Need Statutes of Limitations for Rape

Momentum is gaining to end criminal statutes of limitations for sex crimes. But this betrays both victims and those accused.

Imagine for a moment that, quite out of nowhere, police showed up and accused of you raping someone last Tuesday evening. They even claim to have DNA evidence of your crimes against this person, whom you've never met. How might you go about showcasing your innocence?

Naturally, the first step would be to prove you weren't at the alleged crime scene. If others can vouch for your whereabouts on Tuesday evening, you would give them as alibis. You might offer up receipts from bars visited or taxis taken that night, turn over GPS data from your vehicle, or show evidence of cell phone use—texts, calls, photographs—from this time. Detectives could easily check your word against taxi, ridesharing-service, phone, or bank data, and they might ask around to wherever you drank, dined, waited in line, picked up your kids, or whatever to see if anyone remembers seeing you. Maybe they check surveillance video from your subway stop or a 7-11 you stopped in, or get your apartment building's security footage. Maybe they find a neighbor who saw you pull into your garage, go out back to star gaze, take out your recycling…

The point is that unless you live all alone in the forest, there's a good chance you could establish where you were last Tuesday night, and conjure up enough evidence of it to drive reasonable doubt.

That is, if you're innocent. If you're guilty, all of the above works in the reverse (regardless of whether DNA evidence exists). Everyone who saw you, everywhere you traveled, and everything you paid for could place you at or near the crime scene. And for sexual assault cases, where it often comes down to the word of the accuser against that of the accused, these sorts of details could provide the crucial context needed to get a conviction—especially in cases where an assailant admits to being with the victim but claims the sex was consensual. Catching the accused in a lie about other parts of the evening, finding someone who saw them acting or looking suspicious, checking footage from places visited before or after, etc., might lead to tidbits that could help establish guilt.

Of course, this only holds if the victim comes forward soon after the attack. The key with all these potential ledes is temporal proximity: People's memories from a few days ago are still relatively fresh, security footage is still available, you (the wrongly accused in this scenario) still might still have a relevant bodega or McDonald's receipt lying around. A dorm mate or neighbor may remember seeing the assailant.

But imagine instead that the victim waits three months to file a police report. Some of the above—the nosy neighbor, say, or the pocketed receipts—will likely have been lost (who remembers minute details of some random Tuesday night three months ago?). Give it a bit longer, and more potential clues will have disappeared. Now give it six years, or 16, or 20. By that point it's not just the corroborating or exculpating GPS data, bar comrades, and bank records that are lost. Key witnesses may have died or moved off to unknown places. The bar where staff could alibi you no longer exists. All of this makes it much less likely that a victim will see (long-awaited) justice, that a rapist will be held accountable, and that a person wrongly ensnared will be able to prove their innocence. It's a lose situation all around.

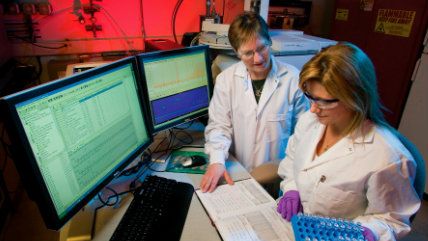

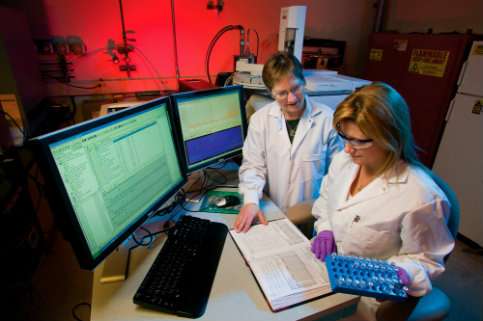

Then there's the question of DNA. Any chance police had of finding useful DNA evidence at the assault location is obviously long gone, but perhaps the victim saw a doctor after the assault and had a medical forensic exam (also known, somewhat unfortunately, as a "rape kit"). This evidence, which would include samples from any semen found plus DNA evidence found anywhere on the victim's body, was sent from the hospital to a state crime lab, where it has been stored in vacuum-sealed bag inside a cardboard box inside a storage freezer for several decades. While DNA evidence does degrade with time, it should still be good for a few centuries—if stored perfectly. Thus far, however, law-enforcement forensics units have been notoriously bad at collecting, storing, and analyzing forensic evidence without making mistakes, and the longer these labs are holding on to a rape kit, the more chance for errors human or environmental. Forensic evidence storage areas in a lot of places are hardly high-tech operations, and policies for handling and keeping such evidence often ad-hoc.

Plus, as Matther Shaer put it in an Atlantic feature last year, "science is only as reliable as the manner in which we use it." And research has shown that the way we interpret DNA is highly subjective. In one 2010 study, researchers obtained documents from a 2002 Georgia rape trial in which two forensic scientists said the defendant could not be excluded as a DNA match for the mixture of sperm found inside the victim (the defendant was found guilty). In the study, the same DNA sample was shown to 17 experienced lab technicians, without context, who were then asked whether the mixture included DNA from the defendant. Twelve concluded that it definitely did not, one concluded that it definitely did, and four said it was inconclusive. "In other words," Shaer writes, "had any one of those 16 scientists been responsible for the original DNA analysis, the rape trial could have played out in a radically different way."

A similar DNA sample, processed long after it was collected and long past the point when corroborating evidence in the case is available, could be a powerful weapon of injustice indeed.

In the past, this hasn't been a big problem. But a host of factors—advances in forensic testing, a culture that's more supportive of rape victims coming forward, states storing rape-kit evidence longer, and a loosening of state statutes of limitations on rape charges—mean we could wind up with a lot more cases where sex crimes that rely on DNA evidence are being prosecuted years or decades after they occur. And if this happens, the results could be bad for assault victims, bad for innocent people, and bad for the concepts of due process and criminal justice as a whole.

But the force is strong with this one at the moment. Since the start of 2017, legislatures in Minnesota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Washington state, and Washington, D.C. have considered bills that would drastically expand or outright end the statute of limitations for pressing charges in sexual assault cases. In late 2016, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law a measure removing the state's statute of limitations on rape and other sexual offenses entirely; prosecution was previously limited to 10 years.

Supporters of these changes argue that certain circumstances may make it hard for victims to come forward in a timely manner. Those abused in childhood may not come to terms with it until well into adulthood. Those in abusive relationships may be afraid to report. Or sometimes victims do report and there's not enough evidence to prosecute at the time but DNA evidence discovered later changes that. But while all of this may be true, none of it holds up to scrutiny as an argument for ending statutes of limitations entirely.

Why not? For starters, most states already provide victims with a pretty long window in which to come forward; more than a dozen states already exclude rape from statutes of limitations, and the majority set the limit at 10 years or more. But these are just the baseline statutes of limitations. In most states, the clock is reset if new DNA evidence is discovered, and doesn't apply at all if the victim was underage when abuse occurred or if the perpetrator has purposefully evaded law enforcement. Some states carve out exceptions for sexual assaults in which serious bodily injury occurred or a gun was used. In other words, we have already found ways to deal with the exceptional cases that allows justice for victims without conceding that all sex offenses can be prosecuted into perpetuity for any reason. We have found ways of accommodating the fear or trauma that may prohibit victims from coming forward immediately without saying that anyone can just decide, four decades after an alleged attack, that now they're ready to see the person prosecuted.

In conjunction with efforts to end statutes of limitations, victims' rights advocates have also been attempting to reform rape-kit collection and storage procedures. The federal Sexual-Assault Survivor's Bill of Rights, passed in 2016, requires states to keep all rape kits for 20 years or until the statue of limitations for rape in that state has expired. It also stipulates that kits must be collected and stored without charge to victims (regardless of whether they filed a police report), that law-enforcement clearly explain rape-kit testing and storage policies to all potential victims, and that victims be notified if tests yield any matches. Sexual assault victims—or "survivors," in current PC parlance—also have the right to request notification if their kit is set to be destroyed and to request that the evidence be preserved.

The legislation was driven in large part by Amanda Nguyen and the nonprofit advocacy group she founded, Rise. Nguyen launched the group after finding out that her home state, Massachusetts, required sexual-assault victims who had a rape kit done at a hospital to either file a police report or file a written request that the evidence not be destroyed. If not, the rape kit would be tossed after six months. Nguyen was motivated by the experience to try and change both federal law and Massachusetts law, and she succeeded. In fall 2016, the state passed a law stipulating that all rape kits must be stored for 15 years.

This week, Nguyen's group unveiled a new video it made with Funny or Die, featuring Orphan Black star Tatiana Maslany. In the spot—a spoof of 1980s and '90s workplace-training videos—Maslany's character advises a colleague to buy a "sexual-assault survivors' utility belt" since the way police treat victims is such a "drag." The colleague, who had been raped recently, was upset about having to "again" petition police not to destroy forensic evidence from her assault.

Here's how Mashable's Rebecca Ruiz described the video: "It may sound like an unbelievable premise, but it actually happens to countless survivors because the laws preserving rape kit evidence vary from state to state, and the backlogs to test DNA are notoriously long." Tyler Kingkade at BuzzFeed described the video as part of efforts "to fix a patchwork of state laws that allow many cities to destroy rape kits before they're tested, sometimes in a matter of weeks."

The impression given by Mashable, Buzzfeed, Funny or Die, Rise, and Nguyen is that untested rape kits from recent assaults are being tossed before crime labs even have time to get to them and that victims' who want rape kits preserved are subject to capricious cops eager to discard evidence, even in the midst of ongoing investigations. It's incredibly misleading, if not outright false.

The truth is that not a single state allows untested rape kits to be destroyed if a case is open. The backlog of untested rape kits that exists in many areas comes from forensic tests dating back decades, before testing for forensic evidence was possible or common—not new tests for new crimes being added to the end of the queue. And, yes, some states will destroy relatively new, untested rape kits after a certain amount of time, but not if the victim files a police report.

What about victims who aren't ready to file charges right away but want the evidence preserved for when they are? No problem—they just have to notify state authorities of this wish. This was what happened in Nguyen's case: forensic evidence was collected, but Nguyen didn't file a police report. That's why she was required to notify the state after six months that she would still like the evidence preserved, and every six months from there going forward.

This doesn't seem like such an unreasonable policy. Perhaps the extension period could be expanded, but it's hardly outrageous for authorities to decide that they won't hang on to random DNA samples for criminal cases that don't exist and victims who have never indicated they want the evidence preserved. And in cases where the victim has not notified law-enforcement about the assault but does want the state to store evidence, it hardly seems unreasonable that they should have to let the state know this.

Advocates like to say that we don't make victims of other crimes beg police to not to destroy crime evidence. But we also don't let victims of other crimes refuse to file a police report, get forensic evidence collected through a third party, and then have the evidence stored in state crime labs at state expense indefinitely on the chance that they someday decide to report the crime.

The bottom line is that we should be encouraging rape victims to come forward and report assaults to police as soon as possible. I understand that there are myriad reasons rape victims are reluctant to do so, and we must be empathetic with regard to people's individual needs and capabilities (as well as respect the wishes of victims who never plan to pursue prosecution). But coddling victims to the point that we obliterate their chances of seeing justice seems a strange way of showing compassion and respect. And this is exactly what we do when we act as if it's all the same if they report an assault immediately, in 10 weeks, or in 10 years.

We also abandon our normal concepts of justice and rehabilitation with this policy. Sure, everyone hates rapists. But a lot of us believe in redemption and repentance, too. A person who robs a house or fails to get affirmative consent at 22 may be a perfectly law-abiding, non-predatory person by 42. They may have atoned entirely. Yet we should treat this rehabilitated person who committed a crime two decades ago the exact same under the law as the guy who assaulted someone last week?

Ultimately, getting justice and encouraging healing for victims of sexual assault needn't require us to abandon basic principles of due process and criminal justice. There's middle ground between making victims request DNA-storage extensions every few months and keeping all rape kits forever whether victims want it or not. There's middle ground between expanding statutes of limitations to cover circumstances where victims can't easily come forward and saying sexual assaults can be prosecuted 60 years after they occur.

Telling survivors to take as long as they need to report an assault, no questions asked and nothing lost, might feel nice from a social services or social justice standpoint, but we betray victims by being unrealistic about the challenges associated with postponing reporting. If our goal is actually justice for victims and prevention of future assaults, we should be promoting proactive policies regarding rape reporting and police reforms that help authorities better handle rape cases, not encoding into state and federal law a right to wait decades to report a crime.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The point is not to convict guilty people and let innocent people walk free. Please. In these sick individual's minds, we are all guilty ("listen and believe"), so the point is to convict as many people as possible.

You think those Title IX kangaroo courts and their show trials are going to stop at the colleges?

and it is amazing that you need to explain to people why there is a statue of limitations.

In their mind, a SOL is only to let guilty people go free. Just like in their mind, people claiming freedom of speech, is just to excuse their 'hate speech'. I mean why else would you need freedom of speech but to protect bad people. Just like a statue of limitations would only protect bad people.

Progs seriously have no concept of history or justice or anything like that. They have their emotions and their in groups for special treatment, and all of their out groups can get fucked.

Who are "these people"? I think you might be painting with a bit of a broad brush here. I can quite understand people being outraged at how difficult it can be to convict someone of rape sometimes and naively thinking that it can be improved with misguided policies like ending SOL or changing standards for evidence. Most of these people aren't radical feminists who think that all men are rapists by virtue of their sex.

I wouldn't say it's an uncommon belief though among people who support this measure (or feminists in general) that as many as 20 or 30% of men are rapists, which means at the least a lot more of us (men) need to go to jail before they're content that rape is being taken 'seriously enough.'

Thus far, however, law-enforcement forensics units have been notoriously bad at collecting, storing, and analyzing forensic evidence without making mistakes, and the longer these labs are holding on to a rape kit, the more chance for errors human or environmental. Forensic evidence storage areas in a lot of places are hardly high-tech operations, and policies for handling and keeping such evidence often ad-hoc.

Shocking.

The impression given by Mashable, Buzzfeed, Funny or Die, Rise, and Nguyen is that untested rape kits from recent assaults are being tossed before crime labs even have time to get to them and that victims' who want rape kits preserved are subject to capricious cops eager to discard evidence, even in the midst of ongoing investigations. It's incredibly misleading, if not outright false.

Shocking.

You're just too jaded, Crusty

Jaded is my middle name.

Thanks for bringing a different perspective to the issue.

Shocking.

I made this point to some mixed company friends during a not-so-recent discussion about the Daily Show (back when it was touted as superior to Fox, CNN, etc.). That News-Comedy, as opposed to news, had an greater interest, if not MO, of getting the facts more or mostly right but then deliberately misrepresenting context or framing the facts or issue wrong and that sound byte journalism, as bad as it is/was, was explicitly exacerbated when employed for comedic or entertainment purposes.

I got a 'huh' followed by a quick change of subject. I'm not sure if it was a dismissive or contemplative 'huh' but the change of subjects was an acceptable response.

but we betray victims by being unrealistic about the challenges associated with postponing reporting.

It's better to play pretensies and feel better about ourselves by not hurting their feelings.

The natural subtext to the entire thing is that women are weak, don't have agency, and generally don't know what's best for themselves. Therefore the state needs to coddle them for up to...well their entire lifetime...in case they decide to do the rational thing through some whim or chance alignment of the stars.

After all, women aren't really people but they are a useful demographic.

At least, this is the subtext in most modern media when women are brought up. Rarely is it that women are people too, and have the same rights and responsibilities as anyone else to report a crime against their person in a timely manner. I'm sure being raped is pretty much one of the worst things that can happen to a person. That doesn't absolve the victim from bringing charges before they're on their deathbed.

Ultimately ENB is right, it hurts their chances of a successful prosecution more than anything else. The character assassination on it's own would tank their case sans same other definitive proof.

Yeah, it does seem that way. I'm sure being raped is a particularly horrible thing to experience. But being beaten or mugged can be quite traumatic too and I don't hear a lot of calls for similar reforms when it comes to those crimes. And how many muggers never get caught or prosecuted? Quite a lot, I think.

I also want to make a point to blame television programs - like CSI, and NCIS, and Law & Order, for popularizing an oversimplified view for both criminal justice system, and well as forensic science.

The criminal justice system is an unjust network staffed largely by incompetents, and forensic science is very flawed. By implying that a victim of sexual assault has forever to be vindicated suggests the system will work in their favor, when there is a very good chance that it will not.

Ding! Exactly this.

And, here's the problem:

"Imagine for a moment that, quite out of nowhere, police showed up and accused of you raping someone last Tuesday evening. They even claim to have DNA evidence of your crimes against this person, whom you've never met. How might you go about showcasing your innocence?"

By waiting for the state to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that I actually did the deed. Then by suing the life out of the false accuser.

What about the rights of the accused to a fair and speedy trial? How is that accomplished by waiting forever?

I would feel much better about 'rape law' if the sanctions against false accusations were EVER put into play. It makes the system look like the judicial regard toward women is that they are frail and even when they break the law, need protecting. This mind set is regressive and brought us the Divorce courts that broke the will of Americans to marry.

When college girls can apparently claim rape retroactively, this seems live an even bigger issue.

Got an ex-wife you divorced 20 years and haven't seen since? Go to jail, she's decided no to be vindictive and accuse you of rape.

The statute of limitation doesn't really matter. But a rape conviction should require physical evidence in most cases, which means that the victim has to see a medical provider and report the rape within a day or two.

Furthermore, "I got too drunk to remember what happened / to consent" shouldn't cut it, neither "I was too embarrassed to report this until months later".

I'm surprised that the consensus here is pro-regulation. It seems to me that the libertarian argument would be on the side of free speech of the accuser with the understanding that the burden of proof on the state becomes exceedingly hard to meet after a number of years.

Defamation - in this context verfiably false accusations - is not protected speech anyway. We can either "let the market sort it out" and leave it up to individuals to litigate such situations for years with questionably-prospective recovery, or we can neuter the ability for the disputes to see the light of day in the first place.

That's what statutes of limitation try to codify; that is, they try to provide an outside, loose bound on the period of time after which claims generally are simply unreasonable. Statutes of limitation are limiting the power of courts and prosecutors, hence they are a limit of government.

None of the arguments presented here is a good enough reason to keep a statute of limitations on the books for sex crimes.

If the concern is innocent people being convicted on questionable evidence, such as testimony of events decades ago; there could be rule saying that such testimony is legally insufficient by itself. But a blanket ban on prosecuting after a certain time period means that some rapists/perps can get away with it even if new evidence (such as DNA or video) surfaces years later ? even if the evidence clearly proves guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

?most states already provide victims with a pretty long window in which to come forward; more than a dozen states already exclude rape from statutes of limitations, and the majority set the limit at 10 years or more?.In most states, the clock is reset if new DNA evidence is discovered, and doesn't apply at all if the victim was underage when abuse occurred or if the perpetrator has purposefully evaded law enforcement?.In other words, we have already found ways to deal with the exceptional cases that allows justice for victims without conceding that all sex offenses can be prosecuted into perpetuity for any reason.

Yes, we have found ways to get justice for victims in those cases, by doing precisely what Brown seems to be arguing against: prosecuting people many years after the crime occurred. The only good reason I can see for not prosecuting is if the evidence is not strong enough.

We also abandon our normal concepts of justice and rehabilitation with this policy. Sure, everyone hates rapists. But a lot of us believe in redemption and repentance, too. A person who robs a house or fails to get affirmative consent at 22 may be a perfectly law-abiding, non-predatory person by 42. They may have atoned entirely. Yet we should treat this rehabilitated person who committed a crime two decades ago the exact same under the law as the guy who assaulted someone last week?

Yes, we should treat them the same under the law ? at least in the sense that they should both, in principle, be subject to being held accountable for their crimes by the justice system if enough evidence is presented to establish proof beyond a reasonable doubt. If it is true that this person has since "atoned", or if there are any other mitigating factors, let the court consider those factors when it comes to sentencing. Or let the prosecution consider those factors in offering a plea bargain. Of course, it is also possible that a statute of limitations will bar prosecution of someone who is still predatory and not rehabilitated.

This image is from World of Warcraft: Wrath of the Lich King. Customized Personalized world of warcraft dragon magic mug, there will be magical changes after adding hot water.

my buddy's mother gets 66 each hour on the internet, she has been out of a job for twelve months.. the previous month her payment was 16114 just working on the internet four hours per day. go here to this

+_+_+_+_+_+_+_+_+ http://www.moneytime10.com