New Federal Sentencing Data Provides a Reminder That the War on Meth Is Alive and Awful

While overall drug sentences decline, federal methamphetamine offenders still aren't benefiting from the last decade of criminal justice reforms.

Federal judges continued to hand down fewer mandatory minimums for drug offenses in 2016, according to data released Monday by the U.S. Sentencing Commission. The trend, which began with the launch of the Justice Department's Smart on Crime initiative in 2014, is a result of federal prosecutors bringing less onerous charges. Of the 19,787 federal drug sentences handed down in 2016, 55 percent were guideline sentences, rather than mandatory minimums. In fiscal year 2010, only 35 percent of more than 24,000 federal drug sentences were not mandatory minimums.

The Smart on Crime initiative clearly had an impact. But it was small and will likely be short-lived. Attorney General Jeff Sessions is reportedly preparing a memo to federal prosecutors regarding drug charging. Sessions has blamed the increase in heroin use on the decline in the Bureau of Prisons population, so I'm guessing his forthcoming memo will instruct prosecutors to resume bringing the maximum charge in federal drug cases. That means more mandatory minimums.

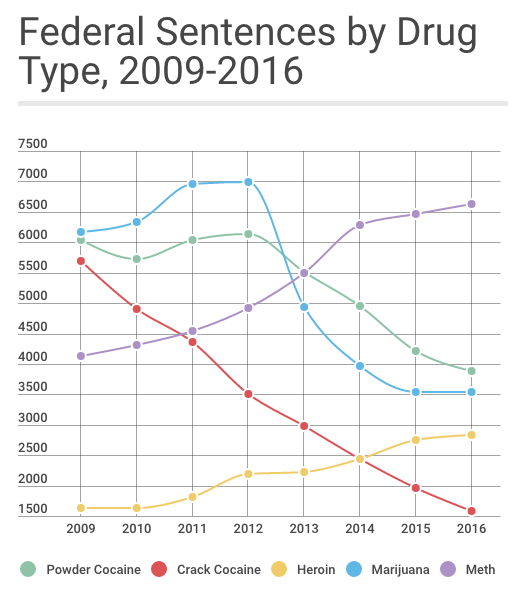

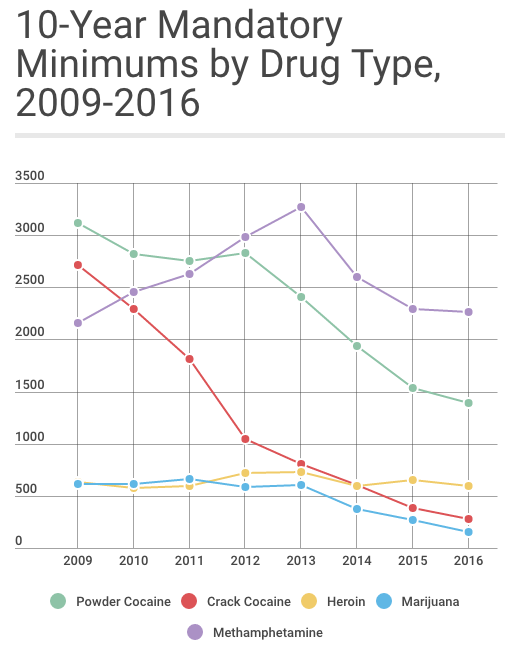

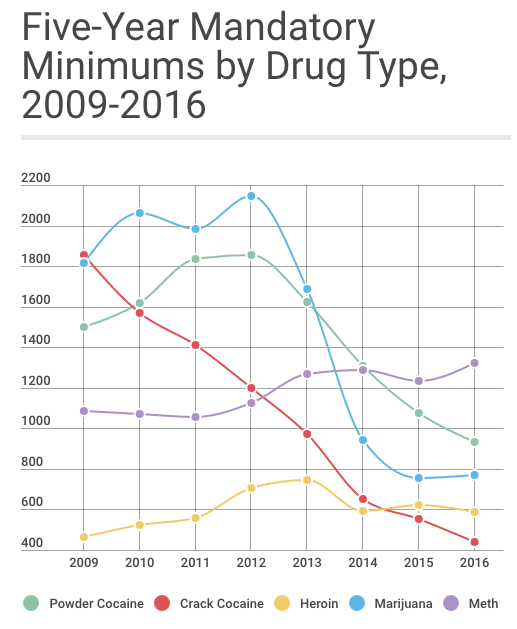

The USSC's data reveals another noteworthy trend: Federal methamphetamine offenders continue to see very little benefit from the last decade's worth of various criminal justice reforms:

(Charts made using Infogr.am with data pulled from the 2009-2016 USSC sourcebooks)

To summarize those charts: Federal drug sentences, both mandatory minimums and guidelines, are falling for every drug but meth. But you wouldn't know it from the national conversation we're currently having about drugs.

It's useful to compare crack and meth in particular. Both have fancier siblings that tend to get less panicky coverage (powder cocaine and prescription amphetamines, respectively); both are used and sold largely by low-income people; and both--up until 2010--required incredibly small quantities to trigger their corresponding mandatory minimums.

Starting in 1986, five grams of crack cocaine triggered the same federal five-year mandatory minimum prison sentence as five grams of pure methamphetamine or 50 grams of a mixture containing any amount of methamphetamine. With the passage of the Fair Sentencing Act in 2010, the minimum quantity of crack cocaine necessary for a five-year mandatory minimum was raised to 28 grams; the minimum quantity for methamphetamine remains five grams. (Five grams, as my former colleagues at Families Against Mandatory Minimums like to point out, is the equivalent of five packets of sugar.)

Why did we change the law for crack but not meth? Well, sentences for crack and powder cocaine had--still have, in fact--a gross disparity. An offender needed 500 grams of powder cocaine, which is sold by every race of offender, to trigger the same sentence as five grams of crack cocaine, which continues to be sold mostly by black offenders. Congress reduced that gap in 2010 to bring some racial justice to the federal criminal code. And that's good. I'll cheer for mercy by any means.

But no legislator has campaigned for extending the same consideration to meth offenders, even though many of the people who sell meth do so to pay for their habits, and we are supposedly living in an era of treatment, not punishment. This is why I cringe a little when critics claim that legislators are responding to opioids more compassionately than they did to crack because opioids are a white drug and crack is a black drug. There is much truth to that observation, but let's not forget that meth--despite its rising popularity as a party drug among gay urbanites--remains a very white and rural drug, and we are taking pounds of flesh from the people who sell it.

From the late 1990s through the late 2000s, every big media outlet probably ran at least one story decrying the meth epidemic. While you don't see as many of those reports now, I've yet to see outlets go the other way, with long, humanizing features challenging draconian sentences for non-violent meth dealers like Mandy Martinson and Melissa Trigg. I wonder why that is?

Show Comments (17)