The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

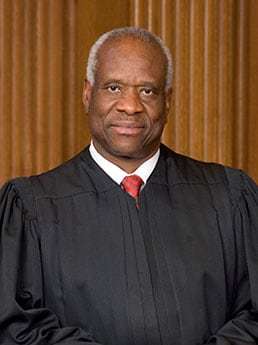

Justice Thomas on why the Foreign Commerce Clause does not make Congress "the world's lawgiver"

The Supreme Court recently refused to hear Baston v. United States, a case involving the scope of the Foreign Commerce Clause, which gives Congress the power to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations." Justice Clarence Thomas filed a forceful dissent to denial of certiorari (beginning at pg. 28 of the linked document), arguing that the Court should have taken the case in order to pare back federal overreach in this field and "reaffirm that our Federal Government is one of limited

and enumerated powers, not the world's lawgiver."

The defendant in this case was prosecuted under a federal law that allows federal prosecutors to go after alleged sex traffickers even if the trafficking occurred outside the United States, so long as "the alleged offender is present in the United States." Mr. Batson is a Jamaican citizen who was ordered to pay restitution for coercing a woman into sex trafficking while he was in Australia. The lower court ruled that Baston's trafficking in Australia was within Congress' jurisdiction because the Foreign Commerce Clause gives Congress the power to regulate any activity that "substantially affects" trade between the US and foreign nations, including - in this case - sex trafficking abroad.

Thomas outlines the troubling implications of this reasoning:

Taken to the limits of its logic, the consequences of the Court of Appeals' reasoning are startling. The Foreign Commerce Clause would permit Congress to regulate any economic activity anywhere in the world, so long as Congress had a rational basis to conclude that the activity has a substantial effect on commerce between this Nation and any other. Congress would be able not only to criminalize prostitution in Australia, but also to regulate working conditions in factories in China, pollution from power-plants in India, or agricultural methods on farms in France. I am confident that whatever the correct interpretation of the foreign commerce power may be, it does not confer upon Congress a virtually plenary power over global economic activity.

As Thomas explains in his opinion, lower courts have fallen into this error by applying the Supreme Court's jurisprudence on the Interstate Commerce Clause to the Foreign Commerce Clause. The former does interpret the power to regulate interstate commerce as extending to virtually any "economic activity" that might have a "substantial effect" interstate commerce, including even the possession of medical marijuana that never crossed state lines or was sold in any market. This is an extremely dubious interpretation of the Interstate Commerce Clause, and it is even more problematic when it comes to the Foreign Commerce Clause, because of the potential for expanding US federal jurisdiction to cover virtually the entire world.

Coercing women into sex trafficking, as Baston apparently did, is a terrible crime. But, at least with respect to his activities in Australia, it's a crime that is properly addressed by Australian law, not the US federal government.

The dangerous implications of this broad interpretation of the commerce power for foreign commerce also undermine the case for the Court's ultrabroad interpretation of the interstate commerce power. If the power to regulate "commerce" does not imply a power to regulate any activity that might have some effect on it when it comes to international commerce, the same is likely true to of interstate commerce. After all, the Constitution literally uses the same word to describe both powers, putting them in the same clause of Article I, which states that Congress shall have the power "To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes."

Thomas is also a longtime critic of the Court's interpretation of federal power over interstate commerce, most notably in his concurring opinion in United States v. Lopez (1995).

I certainly don't always agree with Justice Thomas. But he deserves credit for calling attention to the serious flaws in modern Commerce Clause jurisprudence, both domestic and foreign.

Show Comments (0)