At CPAC, Trump's Big Government Cult of Personality Body-Snatches Conservative Activists

As long as conservatives are applauding a president like Trump, it's hard to see how libertarians will fit within the GOP, or a gathering like CPAC.

A year ago, hundreds of conservative activists planned to protest Donald Trump's appearance at the Conservative Political Action Conference by staging a walk-out in the middle of his speech.

This year, when Trump addressed CPAC, the crowd got to its feet for a different reason. They were giving a standing ovation.

Trump didn't let the moment pass without noting it.

"Sit down, everybody, come on," Trump said, to more cheers. "The dishonest media, they'll say 'he didn't get a standing ovation.' You know why? You know why? Because everybody stood and nobody sat."

Trump has a complicated relationship with CPAC, the nation's largest gathering of conservative activists, power brokers, and professional politicos. He was wildly cheered during an appearance at CPAC in 2015—a reaction, he said Friday, that helped convince him to seek the presidency—and then backed out of an appearance at the event in 2016 during the Republican primaries amid threats of protests and walk-outs.

The crowd at CPAC has an equally complicated relationship with the new president.

"Unless he's had a more dramatic inversion than is really apparent, he's not really a conservative," said Patrick Korton, who saw Trump speak Friday at CPAC. "Everybody here knows that, and everyone accepts it for what it is."

Korton has attended dozens of the annual Conservative Political Action Conference gatherings, including the very first CPAC in 1973, when California Gov. Ronald Reagan addressed a crowd of a few hundred at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C. (the massive conference has long since outgrown downtown hotels; the 44th edition of CPAC was hosted at the Gaylord Resort in nearby National Harbor, Maryland), but he acknowledges that conservatives have never dealt with someone like Trump running the show.

Still, aside from Trump's occasional lack of decorum and his tendency to tweet too much, Korton said he's been impressed with most of what the Trump administration has done during its first month in office. The new presidential cabinet, he said, might be more conservative than Reagan's.

"When he does the right thing, we should be fully supportive," Korton said. "When he does the wrong thing, we have to call him on it."

That, of course, depends on your definition of what "the right thing" might be.

Trump's remarks on Friday were remarkable mostly because of how un-conservative they sounded. Trump talked about expanding the power of the federal government to round up illegal immigrants, to make life more difficult for legal immigrants, to spend untold billions of dollars on the construction of an unnecessary border wall, and to spend more money on the military (though he also bemoaned how tax money is wasted by that very same military).

The president delivered his speech less than 24 hours after the White House press secretary, Sean Spicer, suggested that the Department of Justice could soon take action against states that have legalized marijuana, an unnecessary escalation of the destructive war on drugs.

Those proposals aren't just at odds with the notion of smaller government, but will require a more powerful, muscular government.

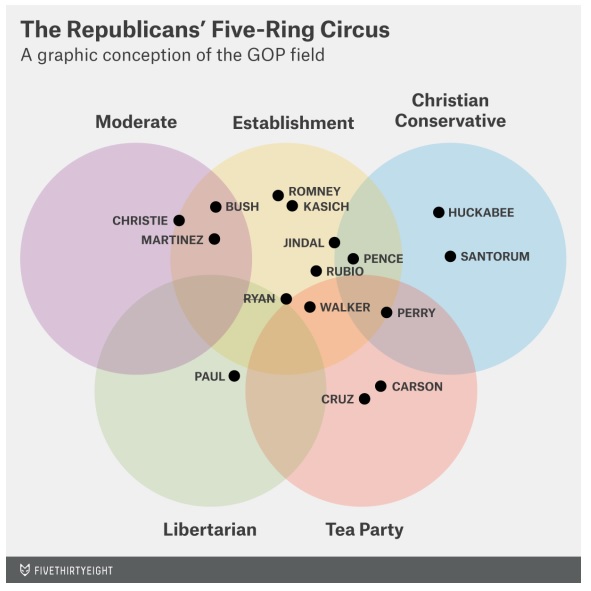

Pollster Nate Silver has postulated that today's Republican Party is best understood as a fusion of five overlapping-but-distinct groups: the "moderates," the libertarians, the "tea party" (those who value fiscal conservatism), the Christian right (those motivated by culture conservatism), and the Establishment.

All the elements are visible at CPAC, but the event is mostly a showcase for the tea party and the Christian right—arguably the two parts of the party coalition most important to the GOP's post-2008 successes. It's the type of place where you'd expect to see Ted Cruz or Rick Santorum, but where Chris Christie (firmly in the "moderate" wing of the party) would seem out of place.

That understanding of the party's structure might need to be revised in the age of Trump, but the basic formulation is still accurate. His cult of personality has already overwhelmed the moderate wing of the party (see: Christie, Chris) and the Christian Conservative wing of the party, which embraced a man who has been thrice married and apparently holds to very few of the principles expoused by the so-called "moral majority" (see: Fallwell, Jerry, Jr).

Now, if this year's CPAC is any indication, Trump's cult of personality is threatening to body-snatch the fiscally conservative activist wing of the party—people energized by the tea party rallies and opposition to the budget-busting policies of Bush and Obama.

People like Albert Bryson, a self-described "independent who usually votes Republican" from Chester County, Pennsylvania who was attending his third CPAC this weekend. Bryson said he first got involved in politics after the 2008 election—he attended one of the first national tea party rallies, organized in opposition to the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

On Friday afternoon, sporting one of those unmistakable red hats, Bryson said Trump's message on immigration resonated with him.

"We should go after the illegal immigrants," Bryson said.

Even if it would require growing the power of government to do it, I asked him.

"Temporarily, it may need to get a little bit bigger so we can get these people out of here as quickly as possible," he said.

Parts of the so-called establishment wing of the GOP have resisted Trump, with limited success. That leaves the libertarian wing of the party, whose most prominent voices were absent from CPAC (a deliberate move, it seems) as perhaps the only remaining portion of the GOP that can claim to be committed to the principles of limited government that formerly unified it.

Gov. Matt Bevin, of Kentucky, made the case for a "big tent" conservative movement focused on cutting regulations and handing power back to the states.

"The people need to be engaged," Bevin told me. "The people who are on the right, the people on the left, the libertarians, the authoritarians, and everyone in between."

But what do libertarians have to gain by fighting for the future of a party that has ignored or abandoned them?

Perhaps that's why libertarian leaders and liberty-minded groups largely were absent from the CPAC stage. Instead, prime speaking spots went to Trump's campaign manager Kellyanne Conway, to his controversial White House adviser Steve Bannon, and (before his appearance was canceled just a day before the convention opened) to alt-right icon Milo Yiannopoulos.

As long as conservatives are applauding a president like Trump, though, it's hard to see how libertarians will be able to fit within the Republican Party, or a gathering like CPAC. Maybe, as Korton suggests, it's possible to find common ground on certain issues—regulatory reform, for instance—while calling out the Trump administration for expanding the scope and power of the federal government in other areas.

Still, it's difficult to understand how a room full of people committed to advancing, in theory at least, the benefits of small government policies could stand and applaud a president with such authoritarian tendencies. Can the conservative movement be taken seriously of they are taking Trump seriously?

"It became necessary to take him seriously," Korton says. "But not necessarily as a conservative."

Show Comments (95)