The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

What a strange allegation, in alleged-inventor-of-e-mail vs. Techdirt lawsuit

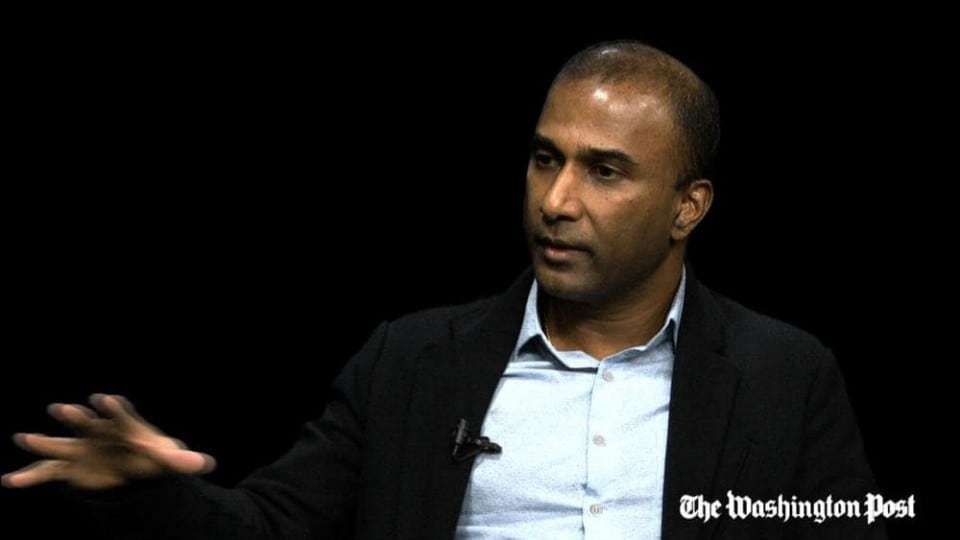

I share David Post's sense that the libel lawsuit by the supposed "inventor of email" Shiva Ayyadurai against TechDirt - which called Ayyadurai a liar for this claim - is generally pretty weak. But there's one paragraph in the complaint that just jumped out at me:

At the time of Dr. Ayyadurai's invention of email, software inventions could not be protected through software patents. It was not until 1994 that the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled that computer programs were patentable as the equivalent of a "digital machine." However, the Computer Software Act of 1980 allowed software inventions to be protected to a certain extent, by copyright. Therefore, in or about 1981, Dr. Ayyadurai registered his invention with the U.S. Copyright Office. On August 30, 1982, Dr. Ayyadurai was legally recognized by the United States government as the inventor of email through the issuance of the first U.S. Copyright registration for "Email," "Computer Program for Electronic Mail System," a true and correct copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit A. With that U.S. Copyright of the system, the word "email" entered the English language.

[Footnote: The Online Etymology Dictionary lists "email" as entering the language in 1982, when Dr. Ayyadurai's Copyright was registered. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=e-mail.]

No - a copyright registration for a program named "email" is not the U.S. government recognizing Ayyadurai "as the inventor of email." No-one at the Copyright Office determines whether a program (or any other work) is a new invention. (Patent examiners may do that, but the Copyright Office doesn't.) Indeed, no-one at the Copyright Office runs the program, reads the source code, or tries to compare the program's description to those of other programs. Indeed, I can today register a copyright on another program called "email," "computer program for electronic mail system." Just as there can be many copyrighted books with the same title, there can be many copyrighted programs with the same title. (Selling a book or a program with a title that's confusing may violate trademark law, but that's a separate matter.)

The function of copyright law is not to recognize inventors of ideas; it's to protect authors of particular implementations of those ideas. That's why you can have a thousand different detective stories registered with the Copyright Office, and none of them be the invention of the detective story (or even of a detective story involving a hyper-rational super-observant detective). And it's why you can have a thousand different e-mail programs - whether or not called "email" - registered with the Copyright Office, and none of them be the invention of e-mail.

Microsoft could register a copyright in its Windows software, and that tells us nothing about who invented Windows. Google could register a copyright in Google Translate, and that tells us nothing about who invented computer translation. Likewise, Ayyadurai's registration of his program with the Copyright Office is not at all the government's legal recognition of him as the inventor of anything.

What's more, while perhaps this claim about the Copyright Office recognizing Ayyadurai as the inventor of e-mail might persuade some journalists, it surely won't persuade a federal judge. Indeed, I doubt a federal judge would even allow this argument to be made to the jury, given the legal irrelevance of a copyright registration to the question whether the government has recognized Ayyadurai as the inventor.

That's why I'm surprised that Ayyadurai's lawyers, Timothy Cornell and noted libel lawyer Charles Harder, even included this paragraph in their Complaint - it just seems to me likely to lessen the credibility of the claim with the judge. I had e-mailed them for their comments several days ago, but have not heard back from them.

But wait, there's one more thing: The footnote, which says "Footnote: The Online Etymology Dictionary lists "email" as entering the language in 1982, when Dr. Ayyadurai's Copyright was registered. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=e-mail." If you check the Oxford English Dictionary, which is generally thought as somewhat more authoritative than the Online Etymology Dictionary, you'll see "e-mail" - defined as "A system for sending textual messages … to one or more recipients via a computer network" dated to 1979:

Electronics 7 June 63 (heading) Postal Service pushes ahead with E-mail.

The first quotation for "electronic mail" in the Oxford is from 1975, and the Oxford editors suspect "e-mail" must have been in use before 1979. It's conceivable that Ayyadurai was the first to use "email," in 1978; I don't know. But the Online Etymological Dictionary citation, like the Copyright Office claim, is a red herring - and, again, one that the judge and jury will easily spot, if necessary with the help of defendants.

Show Comments (0)