Did the Libertarian Party Blow It in 2016?

Objectively speaking, 2016 was the Libertarian Party's best year ever. It was also a savage disappointment.

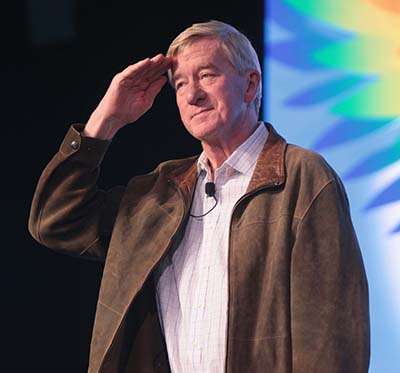

On the positive side, the presidential ticket of two former Republican governors, Gary Johnson of New Mexico and William Weld of Massachusetts, received more than 4.46 million votes, amounting (as of press time) to 3.28 percent of the national haul, smashing the party's previous highs of 1.28 million and 1.06 percent, respectively. The L.P. nominee was on the ballot in all 50 states and the District of Columbia for the first time since 2000, and he outperformed the Green Party's Jill Stein in each one.

"We are the only political party in the country that's growing," Libertarian Party National Chair Nicholas Sarwark crowed the morning after the election. "We've tripled our vote totals [over] 2012.…We control a bloc of the electorate that covers the spread in almost all if not all of the battleground states. We've beaten the other third party…in every single state."

For the first time, the L.P. now has more than a half-million registered voters. The Johnson/Weld campaign raised around $12 million, according to internal accounts (the final Federal Election Commission reports have not yet been filed). That destroys the previous record of $3.5 million, set in 1980 (and $2.1 million of the 1980 total came from billionaire vice-presidential candidate David Koch). The national party pulled in nearly $3 million in additional donations this year, too. U.S. Senate candidate Joe Miller of Alaska received 30 percent of the vote in his race, the highest such total in party history—especially impressive as he had both a Republican and a Democratic opponent. (Generally, if an L.P. candidate for any legislative seat gets double-digit percentages, it's because one of the major parties sat the race out.) GOP defections in 2016 also gave the L.P. sitting state legislators in Nevada, Nebraska, and Utah.

All told, the party has come a long way since its founding in 1971, when a small gang of dreamers hoped it would become a vehicle to get press attention for libertarian ideas.

Still, measured against expectations—let alone the basic standard that successful political parties must win elections—the Libertarian Party had its most disappointing year ever.

"We wanted to win, and we didn't achieve that goal," Johnson's campaign manager, Ron Nielson, acknowledged shortly after the election. "We were hoping to get into the presidential debate, and no matter how hard we tried we could not achieve that goal. After that our goal was to get 5 percent, and for the last 45 days we pushed toward that effort, which was entirely achievable but for the fact that the election came down to such a tight margin between Clinton and Trump. That put pressure on third-party support, and a lot of Johnson support moved in the end toward Trump, or possibly chose not to participate."

While 3.28 percent marked an all-time high for the party, it was also just a third of the campaign's highest polling average, which came in late July. All summer long Johnson had avoided the typical third-party fade, with such forecasters as FiveThirtyEight projecting a finish higher than 7 percent for months on end. But the plates came crashing down over the final eight weeks, prompting much anguish and fingerpointing among activists and supporters.

"The Libertarian Party," wrote 2016 L.P. presidential runner-up Austin Petersen on Election Day, "has blown a chance that it may never have again in my lifetime."

There was plenty of bad news to go along with Johnson's late collapse. One of the party's sitting state legislators, Utah Sen. Mark Madsen, did not run for re-election and will be gone in January. A second, Nevada Assemblyman John Moore, suffered what might be a historic mangling for an incumbent, finishing a distant third place with just 7 percent of the vote. (The third legislator, Nebraska Sen. Laura Ebke, faces re-election in 2018.) The party still has precious few elected officials, and many of those are in officially nonpartisan jobs.

The races that Libertarians were excited about before Election Day vastly underperformed expectations. Massachusetts U.S. House of Representatives candidate Thomas Simmons thought he actually might win against an incumbent Democrat with no Republican in the race, but he ended up with just 10 percent of the vote. Florida Senate candidate Paul Stanton anticipated 5 or 6 percent, after polling as high as 10 percent. He finished with just 2.

Most activists interviewed for this article presented a glass-half-full interpretation of the L.P.'s historic year. But assessing and strategizing the party's fortunes going forward will depend heavily on figuring out what went wrong and what went right with the Johnson/Weld campaign. And that question is still heavily in dispute.

"Wherever it turns out," Gary Johnson predicted on the morning of the election, "I think it's important to point out that last time it was 1 percent, and this time it's going to blow that away. For some, that's just horrible. For others it's recognized for big-time gains."

Pragmatist Converts vs. Stalwart Radicals The record number of credentialed journalists at the Libertarian National Convention in May all seemed to be there to ask the same question: How could the L.P., facing two historically unpopular major-party candidates (including one total novice), do anything but nominate two popular governors with impressive national profiles? Yet even the internally admired Johnson, who had sailed through the process in 2012, needed two highly contested rounds of voting before he won the nomination. And his far more controversial vice presidential recommendation, amid noisy objections on the convention floor, barely squeaked by on a second ballot of his own. (For more on him, see "Bill Weld's Weird Tuesday" on page 56.)

Such intra-party division, while baffling to most outsiders, represents a real split not just in 2016, but in how party members size up next steps for 2018 and beyond. Roughly speaking, a more pragmatic camp wants to keep finding standard-bearers with real-world experience to sell a palatable, big-tent version of libertarianism that stresses fiscal conservatism and social toleration. A smaller group of radicals is increasingly impatient with recent converts who don't seem to grasp some fundamental tenets of the party's philosophy, and they worry that a posture of apologetic libertarianism will dilute the message and repel sympathizers. A third wing shares the radicals' preference for homegrown libertarianism but emphasizes polish and presentation over passion and philosophy.

By calibrating its pitch to the country's normals, the ticket hoped to—and did—drum up massive new interest. But in doing so Johnson and Weld also set up inevitable conflict with some in their own party.

These broad tendencies were on display before, during, and after the May Libertarian National Convention, where 928 delegates wrestled over what everyone agreed was a historic opportunity. Darryl W. Perry, a member of the L.P. Radical Caucus—a group whose goal is to "celebrate and promote the Radical tradition of American Libertarian thought"—ran, representing "the libertarian wing of the Libertarian Party." He came in fourth place with less than 7 percent in both rounds of presidential voting, then warned in his concession speech that "if we nominate two Republican governors as our ticket and we compromise what we believe…THIS. PARTY. WILL. DIE!" In September, citing "the numerous instances of the Libertarian Party Presidential ticket running in opposition to the LP Platform," Perry announced that he was making himself available as a write-in candidate in 17 states plus D.C. (Write-in results had yet to be tabulated at press time.)

Third-place finisher John McAfee, the gonzo anti-virus software pioneer who brought celebrity sizzle and creative weirdness to the Libertarian primary season, also refused to endorse Johnson after the convention, citing the nominee's character and his tendency to rhetorically "compromise" on issues such as gun rights. Among the leading contenders, only runner-up Petersen, the self-styled "freedom ninja" who made his name as a producer for Fox Business Network's Freedom Watch with Judge Andrew Napolitano, actually backed his vanquisher, though only after repeatedly dinging Johnson's muddled position on religious liberty and calling him a "spoiled, entitled brat, prone to public fits."

Such colorful discord conveyed the impression of a party not quite ready for prime time, a judgment enhanced by the convention's most talked-about moment: when James Weeks II, a portly young Michigan activist who'd been running for national party chair, elected to use his speaking time—which was aired on C-SPAN right when viewers were awaiting the results of Weld's second ballot—for a striptease. The act was controversial inside the hall as well as out; Weeks was suspended by Michigan's Libertarian Executive Committee for two years, producing further rounds of recrimination. ("I was far more ashamed of those who turned their heads in disgust than by anything Mr. Weeks did," McAfee wrote on his Facebook page.) For some longtime libertarians who were getting into capital-l party politics for the first time, it was a wince-inducing moment.

Philip Harvey—an entrepreneur who founded the sex product company Adam & Eve and a philanthropist who specializes in distributing contraceptives to the developing world—donated hundreds of thousands to Johnson-supporting super PACs this year. (He has also contributed over the years to Reason Foundation, which publishes this magazine.) Asked whether he'd paid much attention to the L.P. before 2016, Harvey says, "I haven't paid attention to the L.P. even this year. I know very little about it, but it does seem to me that the kind of clownish antics I saw at the convention work very much against the party. If I have anything to say about it, I would try to discourage that, and let the radical, weird material come through as policy."

For all the attention garnered by the radicals and freaks, the pragmatists clearly won the day at the convention, and the party entered the general election behind a softer version of the freedom philosophy, casting libertarianism (in Johnson's oft-repeated phrasing) as "a six-lane highway down the center of the road." By calibrating the pitch to the country's normals, the ticket hoped to—and in fact did—drum up massive new interest. But in doing so Johnson and Weld also set up inevitable conflict with some in their own party.

"A lot of more radical types such as myself are upset because there are some positions that we do not agree with," said Colorado L.P. official, Radical Caucus member, and national committee member Caryn Ann Harlos two days before the election. "But the way I look at it is that the campaign is bringing brand new people in, and then it's going to be my job to make consistent Libertarians out of them. I'm not going to look that gift horse in the mouth; I think that's entirely the wrong attitude."

Johnson defenders rightly point out that the Libertarian alternatives were, in order of popularity: a 35-year-old social-media pop-off with no elected experience, an enigmatic septuagenarian and recent party convert who had been wanted for questioning in Belize over the murder of his neighbor, and a guy who angrily disputes the propriety of government-issued driver's licenses. But in choosing political palatability as a primary virtue, Libertarians ran up against a paradox: Their lead salesman just wasn't particularly gifted at sales. The candidate whose whole strategy was to get into the televised presidential debates was inconsistent at best on TV, by his own admission.

"I constantly apologize for being not the best candidate when it comes to articulating these issues," Johnson said from the Libertarian National Convention stage, in a formulation he would echo throughout the campaign. "So many understand these issues so well, and do such a good job talking about these issues, of debating these issues, discussing these issues, and because of your efforts here we arrived today on the brink of changing America, something that we've always dreamed of. This is the opportunity!"

But was the ability to articulate those positions necessary to seize the opportunity?

'What Is Aleppo?' On the morning of September 8, before Gary Johnson walked on the set of MSNBC's popular program Morning Joe, his polling average on RealClearPolitics was 9 percent, in the ballpark of where it had been for two months. That's when interviewer Mike Barnicle asked him a fateful question: "What would you do if you were elected about Aleppo?" Johnson's wide-eyed, four-word answer became the one and only time that the Libertarian would dominate headlines all campaign long: "And what is Aleppo?"

One week later Johnson saw the last of his 9 percent polling averages, then began hurtling southward. By September 26, the day of the first presidential debate, he was under 8 percent for good. The 7s were left behind two weeks after that, and before anyone had much time to process it, the critical 5 percent threshold—which would have given the L.P. official "minor party" recognition from the federal government, making it eligible for millions in taxpayer financing—was also in the rearview mirror.

In the aftermath, and even with the caveat that both Hillary Clinton and eventual winner Donald Trump had each said demonstrably worse things about the Middle East, many Johnson supporters pointed to the gaffe as a turning point.

"It really deflated a lot of the momentum that we were having," says Judge Jim Gray, the 2012 Libertarian vice presidential nominee, who is now the honorary chair of the Johnson-created nonprofit Our America Initiative.

"Pre-Aleppo, you'd have a lot of strangers giving thumbs up, honks, claps, screams of 'Gary Johnson!'" while out waving Johnson signs or passing out campaign flyers, says the D.C.-based L.P. activist and frequent candidate Bruce Majors. "Post-Aleppo, every eight steps some negative comment, some guy in a loft while I'm going down the street putting Johnson literature on windshields, [was] shouting, 'What is Aleppo?'"

"I shouted back, 'Isn't that the city Hillary Clinton sold weapons to?,' but…"

Aleppo reinforced the impression, among those who were eager to believe or propagate it, that Johnson was ignorant of foreign affairs, disqualifyingly unprepared, and/or just plain goofy. He compounded those narratives by weirdly sticking out his tongue for 10 seconds of an MSNBC interview on September 23, and then volunteering on the same network six days later that he was "having an Aleppo moment" in not being able to come up with the name of Vicente Fox after Chris Matthews asked him to name a foreign leader he respected.

Perhaps the questions were gotchas. Perhaps the media compounded the problem by misreporting his comments, as when his response to Matthews was inaccurately described as an inability to name any foreign leader at all. Regardless, the result was the same for most of the people we spoke to who did retail campaigning for Johnson: Aleppo became the No. 1 objection to the L.P. ticket.

Libertarians, Austin Petersen stressed in an interview after the election, have to realize "that people are going to give [them] a much harder time than a major-party candidate." After all, "Trump doesn't know what the nuclear triad is, Clinton has all her scandals," but something as simple and silly as the Aleppo gaffe can prove fatal. "A Libertarian candidate has got to be on your game," Petersen says.

But September brought plenty of other problems besides Johnson's occasionally tied tongue. National polls, as they always do, began switching their topline results from "registered voters" to "likely voters," thus lowering the results for third-party candidates and making any bad polling trends look worse. The New York Times published an article on September 15 about the Clinton campaign's panic over millennial defections to third-party candidates, and then the nation's comedy newscasts and op-ed pages erupted in a spasm of anti-Johnson content. Environmental activist/billionaire Tom Steyer immediately announced principal backing for a $55 million campaign targeting young people in swing states.

The Debate Gambit The biggest blow to the Libertarian Party's chances came on September 16, when the Commission on Presidential Debates, the nonprofit launched in 1987 and still managed by representatives of the Democratic and Republican parties to gatekeep presidential discourse, announced that the Libertarians failed to meet the 15 percent polling threshold to qualify for the first presidential and only vice presidential debate.

Making those debates had been the campaign's singular goal since even before the Libertarian National Convention. Johnson used it as his primary sales pitch for Weld; the campaign fundraised on a "$15 million for 15%" slogan, and Libertarians hit the commission with two separate lawsuits. (One was dismissed in August but is in the appeals process. The other is scheduled to have first hearings on motions for summary judgment in January.) Weld spoke almost threateningly about the technically nonpartisan body jeopardizing its nonprofit status; Johnson tried pleading for a one-time relaxation of its standards. In late August, the candidate said on CNN that it would be "game over" should these efforts fall short, a prediction that more or less came true.

"No human being not already a sports star [or equivalent celebrity] can get to 15 percent in their time frame," says Sarwark, the party chair. Even though strong majorities in three national polls favored third-party inclusion in the debates, and even though some Libertarians are bullish about the prospects of legal action, nothing happened in time to matter for 2016.

Still, there were moments when even 15 percent looked tantalizingly possible. In mid-July, just before the Republican National Convention, a CNN/ORC poll put Johnson at 13 percent. "Wow, within the margin of error!" recalls Campaign Field Director Carlos Sierra. "We had just started a national TV buy, the SuperPACs were doing their thing, ground game was up and running, we were making tens of thousands of calls a day, visions of how much money we'd get if we got in the debates, all the hiring we could do, offices we could open."

But that proved to be Johnson's high-water mark in the polls. Once it became obvious that he wouldn't make it into the debates, multiple sources with the campaign say, the money spigot pretty much turned off.

"I think if we'd have been in the presidential debates, I think that you would have seen a twentyfold increase in the amount of money that we did raise," Johnson said the morning of Election Day. "I think that we would have raised hundreds of millions of dollars if we would have been in the presidential debates."

As it stands, the campaign did have a banner year raising money, even while falling far short of the $50 million that insiders say is the absolute minimum for running a potentially competitive presidential campaign. In addition to the $12 million for Johnson/Weld, there was also around $2.3 million given to the Gary Johnson Victory Fund (essentially a conglomerate of state parties combining their legal maximums to allow people who'd maxed out on the $2,700 campaign contribution limit to give as much as $117,000 more, which at least one donor, B. Wayne Hughes Jr., son of the founder of Public Storage, did), plus around $3.4 million donated in total to four separate super PACs that supported the campaign.

Asked if he was disappointed that more money didn't flow in, Johnson says, "No, I'm pretty satisfied," then emphasizes that the L.P. routed the competition when measuring votes per dollar. "We raised $12 million bucks, Hillary $1.8 billion, Trump $1.3 billion," he said. "When you do…the votes divided by the money, we're going to get outspent by Hillary 40 to 1."

The 50-State Strategy Not all the theories of what went wrong center on TV brainfreezes or the debates.

"The mistake made," says Austin Petersen, "was the complete dismissal of the 'never Trump' movement and [Johnson/Weld's] play entirely to the left." The ticket's reluctance to attack Hillary Clinton harmed it, Petersen says, as did the tone-deafness to conservative concerns. Johnson "shouldn't have gone to Liberty University and talked about abortion."

These choices provided an opportunity for conservative independent Evan McMullin to steal the campaign's hoped-for Utah thunder, Petersen says. Utah, home base of campaign manager Nielson and campaign spokesman Joe Hunter, was one of a small set of Mountain West states the campaign thought it could excel in. McMullin, a Provo native and Mormon, ended up carrying 21.4 percent of Utah to Johnson's 3.5 percent, and he also topped the Libertarian in the country's second-most-Mormon state, Idaho, though he lagged far behind in the nine other states on which he made the ballot. (Nielson suggests that the Mormon Church's official objection to legalized pot, which Johnson fervently supports, was the prime killer of the L.P.'s chances in Utah.)

Petersen is confident that he could have "raised as much money" as Johnson/Weld via endorsements and support from Republicans disgruntled with Trump. Prior to the Libertarian National Convention he had received an endorsement from longtime GOP strategist Mary Matalin, another boost from RedState editor Erick Erickson, and much positive attention from Glenn Beck. "I was the right candidate for this election cycle," he insists.

Most of the funders and campaign staffers interviewed for this article had a counter view, summed up by Johnson/Weld staffer Andy Craig, who also ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in Wisconsin this November and received an impressive 11 percent in a three-way race (against a Democrat and an independent, with no Republican). "You can't run some random person with no qualifications no one has ever heard of for president," Craig says, "and expect anyone to take it seriously."

The biggest strategic complaint from those interviewed for this story was that the campaign should have more seriously focused on trying to actually win a state, with Johnson's native New Mexico (where he received 9.3 percent of the vote, his best result) being the most obvious choice. If Johnson had treated New Mexico like McMullin treated Utah, perhaps he could have gained the L.P. its first electoral votes since a "faithless elector" gave the party his ballot in its first presidential run in 1972.

Nielson doubts it. "It would have been a selfish endeavor, trying to win a state," he says. "Great for our personal egos," but bad for the Libertarian Party. Johnson's record vote totals across the country, since they came with some impressive state-level results, led to new or renewed ballot access in over a dozen states, including Oklahoma, where the national party spent more than $100,000 to get a Libertarian name on the ballot for the first time since 2000, says party chair Sarwark. Next election cycle, such money can be plowed into actual campaigns instead of time-consuming and expensive petition drives.

McMullin's one-state strategy did lead to those two third-place finishes, but the other nine results came in at under 2 percent. Johnson's national focus got him bronze medals in 47 states plus Washington, D.C. (Johnson's other fourth-place finish came in Vermont, where write-in votes propelled Bernie Sanders into third.) The trick for the party going forward is to make those relationships more permanent. As New Mexico State Party Chair Marty Swinney says, "We don't want people next time thinking, 'Oh, Gary Johnson's not on the ballot, I guess I have to go back to the Democrats and Republicans.'"

One reason for optimism on that score was Johnson's impressive support throughout the campaign among millennials. "It's often said that however you vote twice when you are young, that's the party you are likely to stick with," says Bruce Majors. "I suspect voting Libertarian even once makes it easier to do it again."

The Next Wave The Johnson campaign's biggest long-term influence may be in the first taste of campaigning it offered to thousands of activists: putting political flyers on car windshields and doorknobs, distributing yard signs, manning tables, making get-out-the-vote calls, and talking up candidate and party. Jacqueline Passey Mason, who has been involved in the L.P. for more than a decade, was amazed at the "hundreds" of new faces she saw doing gritty retail work in Virginia.

The campaign "provided an incredible learning experience," says Indiana Libertarian Mark Rutherford, who has decades of experience in the party. "No campaign anywhere doesn't have some bad sides. But the great thing for the party is that even people with negative experience now have experience working on a real campaign with real money, and that's going to be great."

Colorado L.P. Chair Jay North says that in 2016 alone, state party registration (distinct from dues-paying membership) grew from around 33,000 to 40,000, which he credits mostly to growing disgust with the Democrats and Republicans. A similar dynamic was at play among millennials, says Jason Weinman, who ran Youth for Johnson. Younger voters have been attracted to the L.P. "not because of old libertarian dogmas, certainly not people going around saying 'taxation is theft,' not the Non-Aggression Principle, not young people reading Hayek or Rothbard," but rather because of a general sense that the old ways of governing have been discredited.

But new blood exacerbates old conflicts, such as the party's foundational tension between philosophical purity and political success. D.C.-area activist Robert Swartzwelder says he formally joined the Maryland L.P. when he saw too many newcomers with big plans to change the party. "I don't think we should be conforming to public opinion," he says. "We have a sound platform and principles."

And yet even Swartzwelder acknowledges that "I have seen a lot of Libertarians, myself included, be really bad about running off potential new members because we have an abrasive way of expressing ourselves. If we can stop being so off-putting, we have a great opportunity to grow dramatically" while maintaining the L.P's unique identity. "We can't become Republican-lite or Democrat-lite. I don't consider us to be a centrist party."

But centrism is precisely how Johnson and Weld tried to position themselves. And many of the campaign's most influential supporters consciously reached outside the usual libertarian box to bring in converts unfamiliar with the word. "Millions of new young people who didn't know they were libertarians are now aware of and turned on to the ideas of liberty because of Johnson," says Matt Kibbe, who ran the Johnson-supporting AlternativePAC. Kibbe's PAC created an enormously successful online video, starring "Dead Abe Lincoln," aimed at linking voters scared of Clinton with those scared of Trump so that they could both vote for Johnson without fear.

AlternativePAC "very specifically did not go after the low-hanging fruit, not after self-identifying libertarians," Kibbe says. Activists fighting over purity, he warns, "really don't want the L.P. to grow at all, seeing it more as a philosophical debating society or club." But "if you are a political party, winning votes is fundamentally your business."

If Gary Johnson had focused his energy on trying to win New Mexico, some activists now wonder, could he have gained the L.P. its first electoral votes since a "faithless elector" gave the party his ballot in 1972?

The votes for president are the most coveted prize for any political party. Johnson said repeatedly that he's done running for office. Petersen definitely has his toe in the water for 2020. Many activists are fond of Larry Sharpe, an African-American corporate consultant and a close runner-up to Weld for the vice presidential nomination, who stressed the attractiveness of libertarianism to traditionally disadvantaged communities. Weld, meanwhile, said on election night that "the Libertarians have a very clear path in Washington, and I intend to participate in that," but he will likely face fierce internal resistance.

Virginia State L.P. Vice Chair Andy Bakker is adamant about the carpetbagger issue. "The young activists I talk to have a real desire for someone to come from the inside," he says. "Politics is about trust and looking out for your people, and if we keep bringing in outsiders, we can't be surprised if they don't trust us and don't look out for [the L.P.'s interests]. There's a big movement to make sure there are no former anythings on our stage in 2020."

The Next Big Thing? The Libertarian Party finds itself in a place it's never been before, with momentum stronger than ever. But the L.P. still can't manage a lot of things a major party is expected to do. D.C. activist Majors points out that the national headquarters found it hard to cope with such mundane tasks as shipping campaign materials. Internal polling is too expensive, tending to cost at least $20,000 per survey. Libertarians don't currently have a thorough database of their own registered voters, let alone likely prospects, though the Johnson campaign will be sharing elements of its database with the party moving forward. (The specific details of this database sharing are currently covered under a confidentiality agreement signed between the L.P. and the campaign.) "The L.P. doesn't currently have the institutional culture to know how a big campaign is supposed to be run, how to raise money and how to spend it," says Youth for Johnson's Weinman. Nearly every local candidate interviewed laments that neither their state nor the national party machines are able to do much of anything for them other than provide ballot access.

One conflict almost certain to come up at the 2018 Libertarian Party Convention is what to do should the next presidential candidate break through the 5 percent barrier nationally. Clearing that milestone would make the party eligible for federal campaign funds. Most of the activists, candidates, and funders interviewed for this story would have been perfectly happy to see the party's candidate accept the money, which comes from voluntary taxpayer contributions. ("It's a game changer," Johnson says. "You can't compete in politics without money.") But the Radical Caucus is much more circumspect about taking what they characterize as a "welfare check."

What the party needs most, nearly everyone agrees, is more people willing and able to be candidates—particularly if they have the willingness and ability to ask for money, since the L.P. can't really help them with that. Johnson campaign worker and House candidate Andy Craig thinks the party needs to focus on intelligently learning about every state and federal legislative race in which a major-party candidate is running unopposed. Such targeted investments of as little as $20,000–$30,000 via either the party or affiliated super PACs could win state House seats, with as little as $100,000 enough to win a federal one, Craig believes.

Some lifelong activists are glum about third-party prospects in a two-party world. "I have been a member of the Libertarian Party for 32 years and never regretted a moment," says Bill Redpath, credited by many insiders for being the party's prime mover for ballot-access success. "But I do not think it will be an electoral success until some form of proportional representation is adopted in the U.S.," or perhaps ranked-choice voting, an idea Maine voters approved in November.

Being America's biggest third party does come with one distinct advantage: If the other major parties should fracture or dissipate, Libertarians stand ready to expand. "I think in eight to 12 years the Libertarian Party could become the No. 1 party in the United States in terms of size," Bill Weld enthused on election night.

The line between here and there is not necessarily straight. Chris Rufer, a California-based tomato magnate (and occasional donor to Reason Foundation) who gave over $650,000 to efforts related to the Johnson campaign, thinks libertarianism's eventual electoral victory is as inevitable as gravity. But how to get there from here "for now is a puzzle," Rufer says. "It's not going to happen tomorrow and that it's a puzzle makes it interesting."

Jeff Yass, who gave over $1 million to Johnson super PACs and who was new to supporting L.P. candidates this year, says he's not at all discouraged that his investment didn't lead to electoral victory. "No matter how small the chance [to] live in a libertarian world," he says, "I don't have to figure out the odds. The payoff is so high it's worth it."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Did the Libertarian Party Blow It in 2016?."

Show Comments (403)