When Fidel Castro Went on The Tonight Show and The Ed Sullivan Show

There was a time when many Americans perceived Cuba's late leader as a hero.

Fidel Castro ousted Fulgencio Batista's regime on January 1, 1959. Within a little more than a month, he had promoted his revolution on both The Tonight Show and The Ed Sullivan Show.

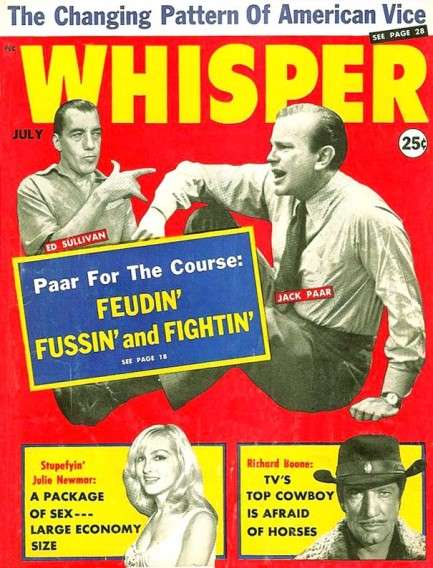

That Tonight Show interview—a warm conversation with then-host Jack Paar—doesn't seem to be online, so you'll have to take my word when I tell you just how strange it looks from the vantage point of 2016. But Sullivan's segment has been preserved on YouTube, and it's one hell of a the-past-is-another-country artifact. Sullivan opens by asking Fidel about his religion (Castro replies that he was raised a Catholic) and inquires about what sports the guerrilla leader used to play ("undoubtedly the exercise you did at school prepared you for this role"). Then it's on to exchanges like this one:

SULLIVAN: In Latin American countries, over and over again, dictators will come along. They rape the country; they have stolen the money, millions and millions of dollars; tortured and killed people. How do you propose to end that here in Cuba?

CASTRO: Very easy: not permitting any dictatorship to come again to rule our country.

By the end of the interview, Sullivan has compared Castro to George Washington:

My point in sharing this isn't to mock Sullivan. (Or Paar, who later joked: "I interviewed Fidel Castro once and he immediately turned anti-American. Of course, it may have been coincidental.") With hindsight, I know that Castro would himself soon be a self-enriching dictator who tortured and killed people. But without hindsight, I probably would have been enthusiastic about the Cuban revolution at that point too. Lots of people were enthusiastic: The rebels had just ousted a thuggish tyrant, and it wasn't yet obvious that they were about to establish a different flavor of tyranny. When you watch that interview, take it as a glimpse at how Castro looked to many Americans right after he came to power.

Over the next decade, that support gradually fell away. By the time Castro proclaimed himself a Marxist-Leninist in 1961, he had lost most of his mainstream boosters. The hip lefties stuck with him for a while after that (listen to a young Bob Dylan singing "Who Killed Davey Moore" at Carnegie Hall in 1963, and check out the crowd's vigorous response when he invokes "Cuba's door/where boxing ain't allowed no more"), and much of the New Left spent the '60s imagining Cuba as an alternative to the Soviet model. But a steady drip-drip of ugly developments, especially Castro's endorsement of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, lost him a lot of those New Left fans. By the '70s, overt support for Castro was much less common. It was still around, mind you—in 1975, Francis Ford Coppola wrote but never sent the dictator a letter that began with the words "Dear Fidel, I love you"—but it was considerably more rare than it had been in the '60s, let alone in those first months of 1959.

But it never disappeared. As a college student, back around 1989, I befriended the sole active member of Michigan's chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. (I was, for all practical purposes, the sole active member of the student libertarian group, so we had that in common.) He sincerely believed in human rights and civil liberties; so when he gave a presentation on campus about a trip he'd just taken to Cuba, he took care to mention some of the more unsavory facts about the regime—remarking, for example, that it was forcibly confining people with HIV.

At that point an old fart by the wall piped up. "They're not imprisoned," he said. "They're quarantined." When I saw the apologetics that greeted Castro's death over the weekend, I thought of that guy.

* * * * *

Bonus links: I'd like to report that libertarians saw through the Castro regime quickly, and for the most part they did. But there was an element that enjoyed the romantic vision of an island standing up to the American empire, so some Fidelista sentiments did circulate through one wing of the movement in the '60s. When Che Guevara died in 1967, one former Objectivist sent Murray Rothbard a letter that declared, "I am sure that his memory will live to haunt both Latin America and the U.S. for decades to come. Long live Che!" And as late as 1971, future gun-rights maven Stephen Halbrook hailed Castro's network of informants, the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, as an anarchistic alternative to "huge central bureaucracy." Points for novelty, I guess.

Show Comments (53)