Did Nonfatal Violent Crime Come Down Last Year After All?

Dueling crime statistics

Today the Bureau of Justice Statistics released a report on crimes committed in 2015. You will be happy to hear that both violent crime and property crimes declined.

You may also be confused to hear that, since it's been less than a month since the FBI released its report on crimes committed in 2015. That also showed property crimes declining, but violent crime went up 3.1 percent and homicides leaped 10.8 percent. What, you might ask, is going on here?

The answer is that it's hard to get solid crime numbers, so several competing means of measurement have evolved—none of them perfect, but each of them complementing the other. The FBI's statistics came from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program, which gathers offenses that have come to the attention of the police. This month's figures come from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), which gets its data by polling people; the idea is to tally offenses whether or not they've been reported to the police.

There are other differences between the two measurements. Most notably, the NCVS does not cover homicides. (Sorry, but you're stuck with that 10.8 percent jump.) Murder is the one crime where there's not a ton of doubt about the UCR numbers: People are much more likely to report a murder than a robbery; and bodies, as the saying goes, are hard to hide. It's certainly possible to get a homicide count wrong, as Chicagoans recently learned, but the UCR figures are the best we've got, and in any event you can't exactly survey the dead about how they died.

There are other crimes that are included in the UCR but not the NCVS (such as offenses against children under 12), and there are crimes that are covered by the NCVS but not the UCR (such as simple assault). But the biggest difference is the NCVS's attempt to include crimes that weren't reported to the police. And that's one reason it's good news that it didn't show a spike last year.

One of the biggest questions about last month's UCR numbers is why homicides rose so much more than violent crime in general. Several people—including me—speculated that nonfatal violent crimes may have surged more sharply than the FBI report suggested; they just didn't show up in the police figures because they weren't reported as consistently as the homicides were. The new NCVS is a reassuring sign that those speculations might not be true.

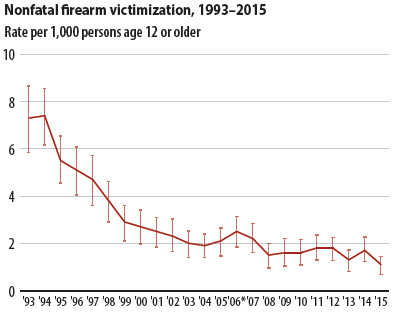

Of course, the NCVS has its limits too. The people its pollsters have the hardest time reaching are low-income minorities without a fixed address—precisely the people who are most likely to be the victims of violent crimes. In a 2014 piece for ProPublica, Lois Beckett pointed out that yet another source of crime data, the Centers for Disease Control's count of nonfatal but violent gun injuries, had been going up over the previous decade even as the NCVS showed such assaults declining. So which was right? On one hand, she noted, the CDC's tabulations may be more likely to include the victims that the NCVS was unable to reach. On the other hand, the CDC figures "are based on a representative sample of 63 hospitals nationwide, and the margin of error for each estimate is very large."

Whatever its limitations, the NCVS gives us a more complete picture of crime in America—and this year, it cuts against some of the sky-is-falling rhetoric that's been sloshing around ever since the UCR numbers were published. Here are some highlights from the report:

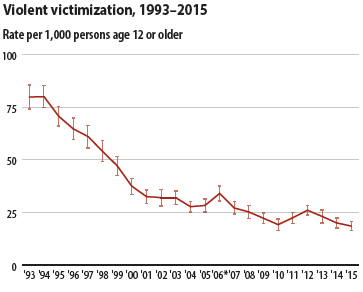

• The overall rate of violent crime declined slightly from 2014 to 2015, falling from 20.1 victimizations per 1,000 people to 18.6 per 1,000.

• Property crime also dipped, dropping from 118.1 per 1,000 households to 110.7 per 1,000.

• Most specific categories of crime logged a decline, though not always a statistically significant one. Robbery, aggravated assault, simple assault, burglary, theft, serious violent crime involving weapons, and serious violent crime involving injury all came down. But sexual assault, serious domestic violence, and serious intimate partner violence all saw slight increases, as did motor vehicle theft.

To read the full study, which includes a more detailed discussion of the differences between the NCVS and UCR, go here.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I will choose the numbers that serve my purposes, thank you very much.

So to sum up:

Good news! (or bad news)

Property crime is down! (or up)

Violent crime is down! (or up)

Things are getting better! (or worse)

Don't worry, be happy! (or go ahead and worry, things are starting to suck!)

Glad we cleared that up!

OT: Jailed 96 days in Mississippi on bogus charge: It is no one's fault?

Pulled over for traffic violations, Jessica Jauch was held for 96 days in a Mississippi jail without seeing a judge, getting a lawyer or having a chance to make bail. She was charged with a felony based on a secretly recorded video that prosecutors finally acknowledged showed her committing no crime.

...

But a federal judge dismissed her case against Choctaw County and Sheriff Cloyd Halford last month, ruling that because she had been indicted by a grand jury on the felony drug charge, none of her constitutional and legal rights were violated.

If you didn't know this already, don't go to Mississippi.

The judge erred. The Grand Jury could have indicted based on perjured testimony.

At a minimum there should be discovery - i.e. the transcript of the sessions pertaining to the allegations against her, the affidavits submitted to the jury or the jurors themselves being deposed regarding what they were told need to be considered in an evidentiary hearing.

If I were a betting man, someone committed perjury.

The problem is not necessarily going to Mississippi. The main problem is bail schedules being too high, civil forfeiture, not forcing judges to review every jailed person within 12 hours, speedy trials and a general lack of concern for low level offenders being given Due Process.

96 days in jail without Due Process is exactly what the US Constitution was designed to prevent. Someone should be sued and this crap will stop. End immunity for this type of government behavior.

So criminals better shots now?

Isn't not covering the murder rate less about the accuracy of the UCR and more that the method for the NCVS isn't conducive to logical results? How do you get a rate above zero to questions like "Were you killed in the last year? was your death unlawful or otherwise suspicious?"

And seriously, why does the CDC have anything to do with shootings other than FYTW? It's not like they're doing consolidated reporting for everything the goes through a hospital.

How do you get a rate above zero to questions like "Were you killed in the last year? was your death unlawful or otherwise suspicious?"

As I wrote: "you can't exactly survey the dead about how they died."

Wow, I'm so bored at work I can't even stay awake long enough to pay attention to my diversions.