Gary Johnson's New Book Offers an Alternative to Major Party "Frustration, Fear and Anger"

Light on policy specifics, and honest about his departures from Libertarian orthodoxy, the book shows Johnson as human, personable, decent, and respectful of work, achievement, and other people's choices.

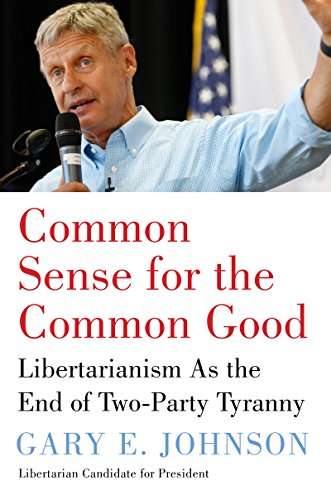

Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson has a new campaign book, published as an ebook only by Broadside Books, a HarperCollins imprint. (Disclosure: The same publisher published my 2012 book Ron Paul's Revolution: The Man and the Movement He Inspired.) Johnson's is called Common Sense for the Common Good: Libertarianism as the End of Two Party Tyranny.

At 78 pages it functions more as an extended pamphlet than a full-fledged book. It's a curious document. Despite crediting a professional co-author, Gary Brozek, in the acknowledgments, the book works as a very apt representation of the tone and personality of Johnson and his campaign, in all its impressive and less-impressive aspects.

The book is rife with the sort of goofy charm that makes some fond of Johnson and some annoyed with him, the spirit that has him bite his tongue on TV news. For perhaps the most egregious (or fun, if you are into that sort of thing) example:

Cue the bat signal! The villainous two-party system is up to no good!

No bat signal needed.

Too bad about the Batmobile, though. It would be kick-ass to have that thing lead a motorcade down Pennsylvania Avenue, "Hail to the Chief" thumping from a subwoofer the size of a washing machine.

Good times. Good times.

Overall, even in the parts meant to be perfectly serious and un-cheeky, the book has the winningly rambling personable tone of a normal, honest guy who doesn't think he has all the answers, really, thinking out loud, not so much like a meticulously composed tome of political philosophy or polemics. And that's the Johnson style.

For example, I don't think Johnson even really tries hard in these pages to convince doubters that a roughly libertarian approach to politics is either common sense or in service of the "common good," though I agree a case can be made.

Libertarians are traditionally more apt to argue about individual goods than common ones and knowingly embrace certain implications of the idea that government should at most protect us and our property from force and fraud that are far from standard common sense.

The book is a bit diffuse if you expected something laser-focused on getting an imagined reader to vote for Johnson. Most of the meat consists of a condensed memoir about both his childhood and his political career before deciding to run for president with the Libertarian Party.

Johnson sells himself convincingly as a good child, good family member, good worker (when he's interested in what he's doing, though he's charmingly open about how soul-deadening he found certain aspects of working for others rather than himself), good businessman and entrepreneur, and successful governor.

Johnson was, he lets you know, the very first governor in New Mexico's history to serve a full eight years, and he gives his usual litany of his vetoing and tax cutting successes, even as a Republican governor in a mostly Democratic state. "I told the people of New Mexico that if they wanted someone who would get along with the legislature, they shouldn't vote for me," he writes. "I liked having a contentious relationship with those state representatives because it helped make things better in New Mexico." (However, when talking about himself as a potential president, he suggests that someone outside the Democratic and Republican nexus could be more effective working with Congress, free of partisan hatreds and baggage.)

Surprisingly for those who follow Johnson lore, he writes almost nothing about his athletic achievements and has only one sideways reference to his affection for pot. Drug policy gets only two sentences in the policy part.

When it comes to why you should vote Libertarian, Johnson rather blithely leaps from facts about the unpopularity of Trump and Clinton to the notion that his version of libertarianism is a middle-of-the-road philosophy of wider appeal. He doesn't, however, draw on any existing polling data to indicate specific desire for libertarian solutions from American voters. He's sharp on identifying "authoritarianism" as the heart of his major-party opponents, and even pretty good at identifying some of libertarianism's core principles while also being honest that he doesn't follow them as rigorously as many who fly that banner do.

After hat-tipping to the Libertarian activists' beloved "non-aggression principle," he fairly discusses where many in the Libertarian Party community disagree with him, and him with them:

The truly fervent Libertarians will tell you that I'm not even really one of them. I'm fine with that. I understand and respect their beliefs. But given the political realities of the time as I project them forward into the future, I don't see some of the things they call for happening. We're not going to close all US military bases around the world. We're not going to abolish all taxes and create user fees. I think a tax on gasoline is a good idea. Take the money from your consumption of the fuel and pay to improve roads? Sound thinking.

But eliminate free public restrooms and institute a usage tax? Not good. Charge for the use of a public park? Impractical and contrary to the spirit of the common good. In general, I don't believe in absolutes or extreme positions. Some members of my party believe that it would be okay if there were no prohibition against owning rocket-propelled grenades, tanks, and the like. I don't. Common sense has to prevail.

While the above might peeve many Libertarians, it might well inoculate him from accusations of wild-eyed radicalism from some potential voters.

One of the book's curiosities is that while the actual policy proposals he discusses at any length (and he discusses none at very much length) try to hit the sides of libertarianism that might be more assumed to appeal to the left—such as being pro-choice, pro-LGBTQ civil rights, and anti-death penalty—as well as the right, such as being pro-Second Amendment and for tax reform that would kill the IRS, he also takes two quite gratuitous, unnecessary to any larger narrative or polemical point, swipes at right-wingers both old and new.

One such instance is when he discusses having to play Goldwater in a school debate and doing a terrible job, largely because he didn't know much about him. And though Goldwater is, for various reasons, generally a hero to the more libertarian elements in the Republican Party, Johnson says of him only that "he had opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. I saw a political cartoon of him depicted as a trigger finger poised to launch a nuclear bomb. I was glad that I'd bombed."

Johnson also takes a few paragraphs for no obvious reason to condemn the Tea Party movement as:

most upset today by the fact that the government hasn't fully exerted its power. It hasn't made the necessary moves to stop Iran from getting nuclear weapons. It doesn't support the use of enhanced interrogation techniques. Worse, it doesn't put God (the ultimate authority) into government.

Also, Tea Party members are not inclusive and harbor many anti-immigration and anti-inclusive views. Comprised in large part of whites—a group who once held a substantial numerical majority in this country—they see their control of voting and policy slipping away and employ various straw men to bolster their position.

It's not a completely outrageous thing to think, and it does position Johnson in a particular place on some important policy issues. But it isn't clear that it's politically advantagous to make positive assertions about himself while attacking a portion of the electorate he might conceivably appeal to otherwise.

Johnson also spends quite a bit of time in this book on strictly electoral process questions I haven't heard from him much on the campaign trail, including getting rid of the Electoral College and questioning the primary system for selecting major party nominees. (Despite what a huge element it has been in his campaign until now, he doesn't discuss the Commission on Presidential Debates and its role as a tool of the two-party system.)

While he spends little time on foreign policy, he does note that Libertarians are "opposed to the unproductive and fiscally wasteful military interventions and regime-change operations that have recently entangled us."

Without saying so in so many words, the biggest likely effect of this book on a sympathetic reader will not be to turn him toward Johnson's policy mix, on which he doesn't even try to be particularly rigorously convincing. This is not a policy book, for the most part.

Its most likely effect is to paint a picture of a choice for president who is not a grossly objectionable human being, one who values autonomy, work, respect, and for the most part leaving other people alone to pursue their own goals in life, one lacking the obsession on the part of major party politicians' with managing and controlling our lives, one who rejects what he discusses at length as the "Frustration, Fear and Anger" that dominates the current major party scene.

Johnson's summation of how he'd make decisions as chief executive of the United States, while lacking appeals to national greatness or offering government as a righter of all perceived lacks or wrongs, is inspiring in its quiet way. The three questions he would

ask in evaluating legislation, policy, and programs are:

? Is it the role of government to be involved in this area of individuals' lives?

? What are we spending, and what are we getting?

? Will this help to solve the problem or make the situation worse?

Johnson also comes across as more genuinely friendly to U.S. economic activity and business growth than tycoon Trump, writing that:

[I] urge everyone to apply everything you know to entrepreneurial efforts. Create a job for yourself. Create a job for others. I'm excited about the sharing economy. I'm excited about the Internet and all the opportunities it continues to provide for entrepreneurs. I simply want government to get out of the way and stop erecting barriers to innovation, entry, and success. Let the markets rule the day and stop marketing more rules and regulations!

While hortatory inspiration isn't really Johnson's natural style, he ends the book with a declaration that the libertarian message relies on appealing to the best aspects of our human souls, that:

Libertarianism arises spontaneously from our essentially positive and hopeful and capable human nature. We don't have to be fearful, frustrated, or angry. Those are choices we all make. If we trust in ourselves and place our trust in those who will return it in kind, we will have better days ahead. Don't just trust me on this.

Trust yourself.

That Johnson can close with that sort of optimism in a year where is seems horrifyingly likely that 40 percent or so of eligible voters will pick Clinton or Trump to lead is its own impressive sort of triumph of human positivity.

Show Comments (39)