Stepping in for the State in Detroit

When the government can't or won't provide services, residents step in.

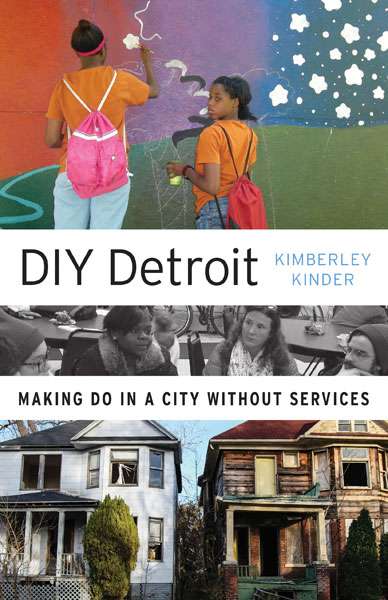

DIY Detroit, by Kimberley Kinder, University of Minnesota Press, 248 pages, $24.95

In 1950, roughly 1.9 million people lived in Detroit. Fewer than 700,000 are left there today. In the bankrupt, crime-ridden city, the government has largely lost the ability to provide the services it once promised. And so residents have taken to plowing streets, picking up trash, and maintaining public facilities on their own.

"When public schools performed poorly, parents looked to homeschooling alternatives," Kimberley Kinder writes in DIY Detroit. "When public libraries closed, residents set up mobile book shares. When ambulances were unreliable, neighbors organized dial-a-ride phone trees to get people to hospitals." And when streetlights failed, a computer programmer named Ellison tells Kinder, people started to "leave their porch lights on all night."

DIY Detroit is filled with these simultaneously inspiring and heartbreaking tales of perseverance and innovation. Unfortunately, to learn about these residents' struggles to keep their community habitable, you have to dig your way through layers of Kinder's tendentious take on why Detroit declined. But the effort is worthwhile. Kinder, an assistant professor of urban planning at the University of Michigan, documents dozens of examples of "self-provisioning"—that is, of Detroiters doing for themselves in a city from which much of the population has fled. "You have to take matters into your own hands," Elena, a young mother, tells Kinder. "'Cause if not, if you wait, then you wait, and wait, and wait. You're going to end up frustrated, and it's probably not going to get done."

How Detroit residents take matters into their own hands depends on their time, resources, and willingness to commit themselves. Those efforts range from disguising vacant homes to demolishing abandoned structures, from creating unofficial parks to standing in for a shrinking police department.

In a city where one in four housing units was empty by 2010 and much of the area is being claimed by an "urban prairie" of returning plants and wildlife, matching potential residents with abandoned but still-livable homes has become an important activity. Empty houses are ripe for picking by "scrappers" who strip anything of value and leave the gutted shell uninhabitable. The best defense is for residents to actively seek new neighbors who will maintain the homes and protect the community from further decline. "Among these recruits," Kinder tells us, "some became official owners or renters, and others lived informally as squatters."

When people are wary of new neighbors who move illegally into abandoned homes, squatters demonstrate their worthiness with public displays of responsibility, such as trimming bushes and openly making repairs.

About half of the 73 residents Kinder interviewed described acting as volunteer realtors. But with so many homes empty, it's impossible to match every dwelling with an inhabitant. That's when remaining residents make efforts to camouflage abandoned structures or render them inaccessible to scrappers and drug dealers. "Residents used disguises, caretaking, booby traps, and sabotage to self-provision a public order the underfunded police department could not provide," Kinder explains. Their efforts might be as simple as keeping the lawns mowed, or they could become more elaborate exercises in illusion, such as putting up seasonal decorations. In worst-case scenarios, residents demolished abandoned structures that had become problems—sometimes legally, sometimes not. "The headaches and expenses of by-the-book demolition," Kinder writes, "encouraged residents to find informal alternatives."

Those informal alternatives enjoy some degree of nudge-and-wink approval from the authorities. Kinder interviews one activist who demolished 113 houses without repercussions. Another Detroit resident described a police operator's response to her phone complaint about a drug house. "Are you sure you've got the right number?" she was asked. "Are you sure you don't want the number for the Fire Department instead?" She took that as a hint that arson might be the way to go.

But it's not just homes that have been abandoned—so have public works. Residents have reclaimed trash-strewn city-owned lots as parks and gardens. Farming is technically illegal in Detroit, but raising vegetables in a city partially returning to nature makes sense both to countercultural new arrivals and to low-income longtime residents alike.

In a place that, as of the FBI's most recent statistics, has the -highest violent crime rate among cities its size in the country, safety is also an obvious concern. Detroit's police department shrank from about 4,000 officers in 2000 to roughly 2,400 in 2013, prompting the police union to issue an (admittedly self-serving) warning to the public that the city was too dangerous to visit. Scattered across the increasingly depopulated urban prairie, city residents have responded with everything from formal police-affiliated civilian patrols to ad hoc street-watching through open windows. One elderly woman, Edna, told Kinder that "it was like a gentleman's agreement that nobody parked on the streets" so that residents could have clear sight lines to keep an eye out for people up to no good.

In many ways Detroit dwellers have rediscovered the value of the old-style nosy neighbors who watch out for each other and perform the ubiquitous surveillance that modern law-enforcement agencies can only hope to replicate with cameras and algorithms. One side of this that Kinder ignores is Detroit Police Chief James Craig's high-profile cheerleading for armed citizens self-provisioning for self-defense and deterrence. "The police cannot be everywhere. This is about personal protection," he told CNN in 2014.

Early on, Kinder cautions us that it's "unfair to expect fragmented self-provisioning to reverse Detroit's trenchant history of disinvestment, racism, and crisis." And indeed, the efforts of the residents she interviews seem puny against the sheer magnitude of the collapse of a major city and the exodus of much of its population and economic base. But these residents' perseverance is the bright spot in this book. It certainly has to be at the core of any effort to salvage a viable community from the wreckage of Detroit.

But what about that -wreckage? What turned once vibrant Motor City into a post-apocalyptic wasteland without an actual apocalypse you can blame?

Again and again, Kinder insists that Detroit is a paradigm of the "neoliberal city," tagging that unfortunate place with a term—neoliberal—that has infested social science. Early on, she writes that her book "explains the effect urban disinvestment and neoliberal policy agendas have on self-provisioning practices." In her conclusion, she tells us that Detroit residents' do-it-yourself work "underscores the need for meaningful, organized, collective responses against neoliberal capitalism and market-based governing." Neoliberalism, she says, involves "market-based policies that emphasize individual, profit-based solutions to collective needs and oppose wealth distribution for social programs."

At least she defined it. The meaning of "neoliberal" is so shifting and obscure that it has prompted a cottage industry of efforts to critique its usage. Rajesh Venugopal, a sociologist at the London School of Economics, wrote last year that the word holds little clear meaning beyond an expression of disdain for all things vaguely market-oriented, arguing that it "serves as a rhetorical tool and moral device for critical social scientists outside of economics to conceive of academic economics and a range of economic phenomena that are otherwise beyond their cognitive horizons and which they cannot otherwise grasp or evaluate."

In this case, Venugopal's critique is on the money. For Kinder, "-neoliberalism" means Detroit was abandoned by investors and prosperous white residents eager to settle in the suburbs and avoid sharing the burden for city services; the local government, meanwhile, surrendered to raw market forces. Is that how it happened?

Some of that's true—white flight certainly was real—but the idea of Detroit as some sort of market-driven dystopia is absurd. "Regulations for food trucks are byzantine, with multiple layers of approvals needed," Michigan Capitol Confidential noted in 2013. "Detroit's archaic ordinances…don't make sense for a city looking to stimulate small-business activity," complained Crain's Detroit Business in 2011. As the sharing economy reached Motor City and brought jobs and convenience with it, Detroit officials repeatedly threatened Uber and Lyft with intrusive and potentially crippling regulations. But if the city discourages entrepreneurial employment, it does its best to pad government payrolls funded by the private sector. Workers were laid off from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department in 2015 only after years of outside complaints about bloated payrolls and inflated costs—in a municipal government that taxpayers can already barely afford.

Lew Mandell, an economist at the State University of New York at Buffalo, recently recounted to PBS' Newshour how in 1972, when he was with the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research, the city commissioned him to examine its then-growing uneasiness at being so entirely dependent on the auto industry. He confirmed the city's concerns and cautioned that other businesses were leaving Detroit (and Michigan) because of "unpopular government policies [that] included relatively high business taxes and what employers perceived as 'unbalanced' worker's compensation laws. There was an overall feeling that government was hostile toward business." In the course of his research, he discovered that officials had received the same warnings from economists 11 years earlier—and even before that in the late 1940s. "Study after study delivered the same results," he said, "which were largely ignored."

Auto-driven prosperity kept Detroit afloat for a few decades. But those concerns caught up with the city as the rules continued to tighten, turning the trickle of non-car businesses leaving the city into a flood—and as the local automobile industry itself lost energy in the 1970s and began its own diaspora.

The people Kinder interviewed don't seem to find her arguments persuasive, either. She writes that "almost none of the residents I spoke with described these activities in countercultural terms. Instead they tried to reinforce—not undermine—the capitalist status quo." Kinder's book would have been that much stronger if she had let Detroiters' efforts to survive in a failing city speak for themselves, without trying to shoehorn them into the story she wished they told.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Stepping in for the State in Detroit."

Show Comments (25)