California Enacts Asset Forfeiture Reform, Mostly Closing Lucrative Fed Loophole

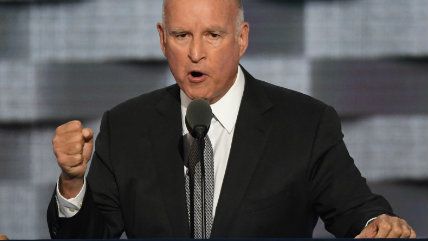

With Gov. Jerry Brown's signature, California mostly closed a loophole that allowed local police to seize property without a conviction by working with the feds.

California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a sweeping asset forfeiture reform bill into law on Wednesday, making California the largest state in the country to roll back a practice that critics say allow police to seize property with little to no recourse for the owner.

With Brown's signature, California becomes the 17th state in recent years to pass some form of civil asset forfeiture reform. Nebraska and New Mexico have banned the practice outright.

Civil asset forfeiture allows police to seize property—most often cash and cars, but even flatscreen TVs, video game systems, and houses—suspected of being involved in a crime. Police do not have to convict or in some cases even charge someone with a crime to seize their property. Law enforcement groups say the practice allows them to target the ill-gotten gains of drug traffickers and organized criminals, but civil liberties advocates say the perverse incentives and lack of safeguards lead just as often to everyday citizens being shaken down for cash.

California's new law will require police to obtain a criminal conviction before they can forfeit assets under $40,000 and—more significantly—receive payment from the federal government's revenue sharing program for the seizure. While the law will still allow large-scale seizures without a conviction, the bill's sponsors say it will mostly close a loophole that police departments used to circumvent previous state law.

"It's clear based on national media coverage, and hundred of calls that have come into my offices from people all over my state telling us about egregious abuses, that this was a bill we couldn't let die on the floor," California state senator Holly Mitchell said in an interview with Reason earlier this summer. "It seems reasonable to me that if you can't convict me of a crime, you can't assume my assets were gained through illegal activity."

Under previous California law, a conviction was required to forfeit property valued under $25,000, but that did not stop local and state law enforcement from working with federal task forces, where there are no such rules. Working with federal law enforcement allows local police to keep up to 80 percent of the proceeds from asset forfeitures they participate in.

According to a report last year by the Institute for Justice, a libertarian-leaning public interest law firm that has challenged asset forfeiture laws in several states, the Justice Department paid local and state agencies in California more than $696 million between 2000 and 2013, compared to $23 million in proceeds from state-level seizures.

"For too long, local and state law enforcement agencies have exploited a loophole in forfeiture law: the federal 'equitable sharing' program," the Institute for Justice's Lee McGrath said in a statement. "Because the federal government does not require a criminal conviction and pays a greater percentage of forfeiture proceeds back to state and local law enforcement than happens under state law, California agencies have routinely participated in equitable sharing."

Mitchell introduced a similar bill in the California legislature last session, but it was voted down under opposition from state law enforcement groups, who said it would have cut off millions of dollars to local police and crippled their ability to go after drug cartels and organized crime. This year, Mitchell and other legislators reached a compromise with law enforcement groups that they say will preserve police's ability to go after major drug traffickers while still protecting vulnerable citizens from petty and abusive seizures.

Earlier this year, the American Civil Liberties Union of California released a report finding that 85 percent of the federal asset forfeiture money flowing into the state went to departments that police minority communities, and that half of the DEA seizures from California involved people with Latino surnames. In 2013, the Drug Policy Alliance calculated the average forfeiture in California to be roughly $5,100.

"Solutions like SB 443 give communities plagued by injustice some relief," Zachary Norris, executive director of the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, said in a statement. "Low income people simply do not have the means to hire an attorney to get their lawfully earned cash returned to them. When their money gets taken by law enforcement, it's a family crisis affecting rent, food, everything."

Show Comments (9)