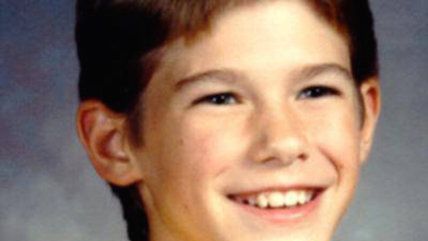

Body of Jacob Wetterling, the Missing Kid Who Launched the Sex Offender Registry, Found After 27 Years

Tragedy makes for terrible public policy.

The remains of Jacob Wetterling have been found in Minnesota. Jacob was abducted in 1989 at age 11. It was a crime that scared, scarred, and deeply saddened people around the globe. As his mother Patti told the Minneapolis Star Tribune on Saturday: "Our hearts are broken. We have no words."

As the Star-Tribune explained:

Jacob was snatched off his bike, half a mile from his home, by a masked man with a gun on a dark October night. Danny Heinrich, a suspect first questioned shortly after Jacob's disappearance and now in federal custody on child pornography charges, gave investigators the information that led to the boy's hidden grave.

The paper added that the authorities did not give much more information about why Heinrich, who has been in federal custody almost a year, suddenly decided to confess the whereabouts of the body.

Maybe we will learn more, maybe not. What hurts most is that whatever ray of hope the parents might have held onto is gone. It is painful to even imagine that light going dark.

It is painful in a more intellectual sense to contemplate the effect that Jacob's unspeakable fate had on American families. Not only did it grip us with dread, that dread—and anger—directly paved the way to the sex offender registry. As Jennifer Bleyer explained in this extraordinary article in City Pages about Jacob's mother, Patty, in 2013:

[T]he Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act…was part of a landmark violent crime bill in 1994 that required law enforcement in every state to maintain registries of convicted sex offenders and track where they lived after being released from prison.

Two years later, Megan's Law mandated making the registry public. As Bleyer notes:

Virtually all the major laws regarding sex offenders have been passed in the wake of grisly, high profile crimes against kids and, like Megan's Law, they bear victims' names as somber memorials. The laws tend to fuel the impression that sex offenders are a uniform class of creepy strangers lurking in the shadows who are bound to attack children over and over again.

That's what Patty Wetterling used to believe about sex offenders, too. Yet over the course of two decades immersed in the issue, she found her assumptions slowly chipped away. Contrary to the widely held fear of predator strangers, she learned that abductions like Jacob's are extremely rare, and that 90 percent of sexual offenses against children are committed by family members or acquaintances. While sex offenders are stereotyped as incurable serial abusers, a 2002 Bureau of Justice study found that they in fact have distinctly low recidivism rate of just 5.3 percent for other sex crimes within three years of being released from prison.

Though the term "sex offender" itself seems to reflexively imply child rapist, a broadening number of so-called victimless crimes are forcing people onto the rolls.

On this sad night, I won't get into all the reasons the public sex offender registry hasn't made us safer. You can read the Bleyer piece to see how Patti Wetterling herself has come to question this legacy of her son's disappearance. And she's not alone. Just a few days ago the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit in Michigan declared that many of the registry's ever-increasing requirements are unconstitutional. It is terrible how bad crimes make bad law.

But the real point tonight is that one young man did not get to live out his days. His family has lived without him for 27 years, and they have just learned they must live without him forever.

We pass laws because we wish there was a way to ease this sadness. It's an understandable impulse, even if the result seldom makes for good public policy.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Similarly some parents whose children died from drug overdoses are starting to realize that prohibition isn't the answer.

If you want to scare your kids straight, get high in front of them when their friends are around. The humiliation alone after forcing them to hang out while wasted should be more than enough to scare them straight.

I am making $92/hour working from home. I never thought that it was legitimate but my best friend is earning $14 thousand a month by working online, that was really surprising for me, she recommended me to try it. just try it out on the following website...go to this website and click to Tech tab for more work details... http://goo.gl/RSVRhj

I am making $92/hour working from home. I never thought that it was legitimate but my best friend is earning $14 thousand a month by working online, that was really surprising for me, she recommended me to try it. just try it out on the following website...go to this website and click to Tech tab for more work details... http://goo.gl/RSVRhj

My brother's friend Bryan showed me how I can make some cash while working from my home on my computer... Now I earn $86 every hour and I couldn't be happier... Before this job I had trouble finding job for months but now when I got this gig I wouldn't trade it for nothing. Start this website

go web and click tech tab for more info work... http://goo.gl/AzTMwA

My brother's friend Bryan showed me how I can make some cash while working from my home on my computer... Now I earn $86 every hour and I couldn't be happier... Before this job I had trouble finding job for months but now when I got this gig I wouldn't trade it for nothing. Start this website

go web and click tech tab for more info work... http://goo.gl/AzTMwA

my co-worker's ex-wife makes $72 every hour on the computer . She has been fired for eight months but last month her paycheck was $21092 just working on the computer for a few hours. pop over here..........

?????? http://www.businessbay4.com/

Wouldn't it have been better for all had an impostor come forth with a convincing claim to have been the abductee? Everyone would've been made happier by such a lie. He could've become friendly w the family, etc. And maybe he could've eventually come into some $. Plus, his story alone would've been worth $.

It is too easy to get into an online argument, but I will say that your post is ludicrous. If he were trying to be funny - even though it wasn't - then at least everyone would know not to take you seriously.

A friend of mine is on the sex offender registry. His crime? Pissing in an alley while stumbling home from the bar.

Yeah, how is that possibly on the same list as Wetterling's murderer? That sick fuck started out by stopping kids on bikes and "groping" them, frequently enough he was known as Chester the Molester. Then he got one poor kid and raped him at gunpoint, told him to run away and not look back or he'd be shot. The kid (now 39) ran and did not look back, but has helped many times with the Wetterling case because it was so similar. So his life is wrecked to some extent. And then that criminal bastard (Wetterling's killer) finally graduated to raping and murdering Jacob Wetterling.

He stopped Jacob and his brother and their friend at gunpoint, asked them all their ages, told the other two to run into the woods or he'd shoot them, and picked Jacob as his victim. Special place in hell for that sick fuck.

But yeah, put him on the list next to your drunken incontinent friend. And while we're at it, let's equate wolf-whistling and rape as equivalent "sexual assault". What could possibly go wrong?

I like your handle, but I won't click the link.

It's that rap video of Keynes debating Hayek. Pretty good way to introduce Austrian economics to friends who are semi-interested but have been thoroughly indoctrinated that Keynesian economics and endless stimulus is the way to go.

I still fear clicking the link. But if you are braver than me, you may like this.

Yup! the one you posted is part one. I prefer to get people hooked on part 2 first (the one to which my handle links), because of better production values and a more catchy tune. But it's from the same folks.

If you happen to know, tell us: Does being "only" a Level 1 offender (I assume it was public indecency or something) vs Level 3 mitigate your friend's circumstances in any way, or is he effectively heaped in with the horrific criminals who actually harm innocent victims?

I know they distinguish "Levels" but it seems like it would be pretty damning to come up on a background check as being on the registry regardless of level. Which is silly. An 18 yr old sleeping with a consenting 17 yr old girlfriend/boyfriend, public exposure while drunk, and child molestation are very, very different things.

This is another example of bad crimes making bad law. More like bad crimes making unconstitutional laws.

The SCOTUS's decision that megan's law was deemed constitutional was wrong and the ridiculousness has continued to 2016. There is nothing in the Constitution that allows government intervention on where you can live, work or entertain yourself unless you are a criminal. By criminal, the constitution means convicted criminal still under punishment.

-VIII Amendment

If the government is deciding where you can live, aren't you still under punishment?

Except you are not on probation or parole or in custody. Which is the major factor why it's unconstitutional.

The '94 crime bill. The gift that keeps on giving. Times 100,000.

Everyone's heard of Megan Kanka and "Megan's Law", but I think few know the name Jacob Wetterling. At least, it didn't ring a bell with me. I had no idea that sex-offender registries existed before Megan's Law, but were internal to law enforcement. I do remember some debate about how much access the public should have to these registries, but that was after Megan's Law. There probably should be a rule against using the names of children, or any victims, in the titles of criminal statutes.

I live in Minnesota, so I've heard more about it than i'd expect the rest of the nation to.

One of the mini-tragedies that the core tragedy of Jacob's death spawned in this case was that the parasitic Minnesota Democrat party (locally called the DFL for Democrat-Farmer-Labor, as if to say DIBS! on those latter categories) claimed poor mom Patty Wetterling and made her run for US Congress twice, then US Senator, with no prior political experience. (She lost.) They even offered for her to run as Lt. Governor (she declined). They tried blatantly to exploit the pity we all had for her. Fortunately, reason (drink!) prevailed and she was not elected.

Her campaign did help solidify in my mind the concept that "Sometimes bad things happen to good people, but it doesn't qualify them to govern."

Nice job. I thought about this very point all day and couldn't come up with a Minnesoda Friendly way of putting it. I feel sorry for any parent who loses a kid, but Patty Weterling was blatantly used as a political prop by the DFL here for many years.

My biggest disappointment was that Michele Bachmann never said anything too loony in her debates with Wetterling when they were running for the same Congressional seat.

Man, when I was in the GOP as a mere delegate, Michele and her entourage lobbied me to vote for her in her run for the 6th US CD election (which she eventually won). She is a scary beeyotch. I was pulling for the little-known Phil Krinkie, a business man who was president of the Minnesota Taxpayers Association (or whatever it was called). Michele was creepy wide eyed bunny boiling level nutjob. Sadly, when she went against MN governor Tim Pawlenty in 2007-2008 campaign, she sunk him by bringing up local MN politics that nobody outside 100 miles of minneapolis gave a shit about but she managed to get him to drop out. Seriously, if he had enough money to hang in there, he could have won the whole thing.

I should have specified that the 2007-2008 campaign to which I refer was the presidential primary of the GOP.

In due fairness to Patty Wetterling the Congressional district that she ran in is one of the most conservative in the state. It is R+10 on the Cook PVI scale. If she had lived in a more DFL friendly district then she could have been elected to Congress.

Not knowing anything about you, but I would guess you were too young at the time. For me his abduction has stuck with me. I was in high school at the time, and although I was a couple States away, his picture was posted everywhere I went. His was the first missing child poster that I really truly noticed, because it was everywhere, but also because I thought I knew where he was.

A neighbor of mine looked surprisingly like him. I was in class with his older sister, and we lived a couple houses apart, but I hardly knew them as they were so reclusive. I wondered if my neighbor was Jacob Wetterling. I can recall every time I saw the posters looking over every detail so I could be certain that he was not Jacob. My neighbor was a 1.5 years older... but maybe the age was a cover. He was slightly taller, probably because he was slightly older, and kids grow. The only thing that kept me from calling the Police to offer a tip, was that they had moved in down the street 2 years prior to Jacobs Abduction, but I had known his sister for those 2 years since we were in class together, but I had not really known him. I recall talking to my Parents about the similarities, and being assured they are not the same.

Every time I have ever seen his picture I have been haunted, that maybe I should have called the police anyway, for fear that someday my neighbor would have turned out to be him.

Well now you have resolution. It is admirable that you paid attention and didn't overreact.

What a tragedy all around. Even you as a tettiery observer were harmed by this crime. People can be awful.

Tertiary. Ugh.

It's a universal law: All laws named after dead children will be terrible.

We pass laws because we wish there was a way to ease this sadness. It's an understandable impulse, even if the result seldom makes for good public policy.

That applies to most laws, and an entire philosophy of government, if you ask me. We've got problems so we must suggest solutions. Trillions of dollars spent on solving problems that somehow still haven't been solved and too few stop to wonder if maybe it's not because we're not doing enough to solve the problem but maybe because problem-solving is a fool's errand. Maybe start thinking of how best and how cheapest you can ameliorate the problem and then let it go. There's no solutions, there's just trade-offs. How far can we go trying to solve this problem before we create problems worse than the problem we're trying to solve?

And "if it saves just one life..." is neither a trade-off nor a solution, it's just a retarded denial of reality. Saving lives costs money, money that could be used to save lives. Spending trillions of dollars saving unfortunate people of one sort of another sounds admirable - free food! free housing! free healthcare! free education! free retirement! - but where you gonna get the trillions of dollars? You're gonna bankrupt the entire damn country in the name of saving unfortunate people? How the hell is creating 300 million poor unfortunates a solution to the problem of poor unfortunates?

I actually agree with your sentiment, unfortunately, but then: a democratic society functions on what is best for the many, not the few, or the one. I won't even touch the "bleeding heart liberal" views on social ills, but I think you covered it pretty well.

However, if there is one category of offender that can cause endless damage to multiple victims, has little chance of rehabilitation, and should be placed in a "special" category for law enforcement and sentencing, it is pedophiles.

Many people's comments, as well as this Blog, point out the inadequacy of labeling every incident from urinating in public to what is technically statutory rape involving boyfriend/girlfriend if underage, as a sexual offence deemed worthy of Registry, and therefore seen as all 'equal'.

So, perhaps lawmakers should be encouraged to target the most serious offenders, predators who rape and often murder children, as worthy of special legislation which would, at least, keep them from harming more victims. In my opinion, all (serial) rapists should be considered carefully before any chance of parole is ever considered.

The only real solution is that we put everyone on the list and then it's up to you to prove you aren't supposed to be on there. I mean if you aren't doing anything wrong...

I assume you are being facetious.

Yup, he is. Hyperion is good people.

Very interesting points. I have a diploma in Criminology and am a former law enforcement officer, but your blog is food for thought - I will research those ideas some more!

Interesting. If you stick around here in the Reason comments, you will find some reasoned debate, cautious optimism, hopeless cynicism, and many things in between (as well as complete DERP from our favorite trolls). There is much sarcasm and ribbing, so don't be too sensitive either. Probably the best "anonymous" commentariat there is on the web.

And best of all, Sugarfree's great works of fiction!

Start working at home with Google! It's by-far the best job I've had. Last Wednesday I got a brand new BMW since getting a check for $6474 this - 4 weeks past. I began this 8-months ago and immediately was bringing home at least $77 per hour. I work through this link, go? to tech tab for work detail,,,,,,,

------------------>>> http://www.works76.com

Start working at home with Google! It's by-far the best job I've had. Last Wednesday I got a brand new BMW since getting a check for $6474 this - 4 weeks past. I began this 8-months ago and immediately was bringing home at least $77 per hour. I work through this link, go? to tech tab for work detail,,,,,,,

------------------>>> http://www.works76.com

Have some fucking respect, spambot.

Maybe your overlords can enhance your filter to avoid posting this pyramid shit on articles about ABUSED DEAD CHILDREN

On the other hand, I have an almost blind albino squirrel running around my yard right now, and that does my heart good.

Now here ^ is a group of people who ought to be on a registry.

We pass laws because we wish there was a way to ease this sadness.

*And* because of the JOBS, right? RIGHT?!

Unfortunately, I think you are right.

The purpose of any system, in this case the "justice" system, is to propagate itself, and increase if possible.

Solving the 'problem' it is tasked with is a secondary distraction, and threatening to its existence.

And as for laws, they don't actually DO anything, at least not preventative.

The good ol' days of a duel, or a Wild West gunfight, solved the problem more quickly and permanently.

The irony is that if the registry existed a hundred years ago, it wouldn't have prevented any of these crimes. First of all, many of the people who committed these "dead children" crimes were not even on the registry. Or, they were the truly criminal ones that no law would stop. Laws are only for good people.

Start working at home with Google! It's by-far the best job I've had. Last Wednesday I got a brand new BMW since getting a check for $6474 this - 4 weeks past. I began this 8-months ago and immediately was bringing home at least $77 per hour. I work through this link, go? to tech tab for work detail,,,,,,,

------------------>>> http://www.works76.com

my classmate's aunt makes $74 /hr on the internet . She has been fired for eight months but last month her paycheck was $12598 just working on the internet for a few hours. find out here now

?????? http://www.businessbay4.com/

Olivia . I can see what your saying... Matthew `s storry is great, last tuesday I bought a gorgeous BMW M3 since I been earnin $9756 this last month and-a little over, 10/k this past munth . without a question it is the most-financialy rewarding Ive ever done . I began this 7-months ago and practically straight away earned more than $71 per hour . More Info..

???????>>> http://www.earnmax6.com/

This is indeed tragic! There are however problems with the official story and there`s a larger cover-up going on than meets the eye. This story broke 2 weeks after an interview with David Shurter, who claims his father was the kidnapper of Jacob and many other children in a VIP paedophile ring that includes high rank politicians. The inconsistencies in this story includes: Jacob Wetterling was abducted October 22, 1989 at 9 PM in Minnesota at night on a deserted road that had no street lights. We are NOW being told that Jacob's abductor had panty hose over his face- but we have detailed abductor pics that were distributed directly after the abduction and there is absolutely NO WAY this could be possible considering the circumstances.The abductor pics being presented NOW are NOT the ones that were presented by the police in 89. And comparing the abductor Danny Heinrich to his abductor pic- we are beinglead to believe that in 28 years the man HASN'T AGED. He looks JUST LIKE the abductor pic they are presenting, which is different from the other four that came out immediately after the abduction. And we can't forget he was 27 at the time. Also, the 911 calls supposedly went missing.

It was a crime that scared, scarred, and deeply saddened people around the globe.

Stupid hyperbole alert. You seriously intend me to believe that people in China (or pick your own distant country) were "scarred" by the abduction of some random American kid?