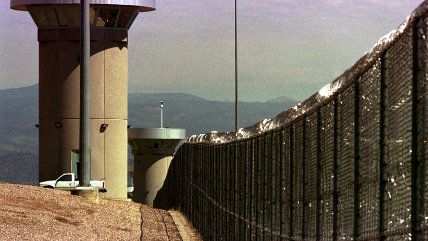

America's Jails and Prisons Have Become Cruel, Expensive Institutions for the Mentally and Physically Disabled

Inmates in prisons and jails are three to four times more likely than average to report having a disability, new report finds.

People with mental and physical disabilities are dramatically overrepresented in U.S. jails and prisons, according to a report released Monday by the Center for American Progress.

According to the report, "Disabled Behind Bars," 31 percent of those in prisons and nearly 40 percent of those in jails report having at least one disability. Fully half of women in jails have at least one reported disability.

Compared to the general population, people behind bars in state and federal prisons and jails are three and four times as likely to have at least one disability, respectively. Down syndrome, autism, dementia, intellectual disabilities, and learning disorders are among the most commonly reported disabilities, according to the report.

Once behind bars, people with disabilities can find themselves placed in solitary for lack of appropriate accommodations, despite federal disability laws that mandate equal access to all services and activities for those in custody with disabilities. They're more likely to be abused by guards, have their treatment and medication regime disrupted, and have a harder time overcoming the considerable obstacles a criminal record puts on finding steady work and housing, the report says.

"Mass incarceration of people with disabilities is unjust, unethical, and cruel," the report states. "But it is also penny-wise and pound-foolish, as community-based treatment and prevention services cost far less than housing an individual behind bars." The report cites a 2014 study that found jailing a person with serious mental illness in Los Angeles County costs more than $48,500 per year. "By comparison," the report goes on, "the price tag for providing Assertive Community Treatment, or ACT, and supportive housing—one of the most intensive, comprehensive, and successful intervention models in use today—amounts to less than $20,500 annually."

At a White House briefing Monday on criminal justice reform and disability, the report's main author, the Center for American Progress' Rebecca Vallas, said the wave of de-institutionalization in the 1960s and 1970s—when the U.S. shuttered many of its mental institutions—was widely greeted as a positive development, but it was not accompanied by new investments in treatment, leaving police and jailers as the primary mental health service providers.

"We effectively traded one form of mass institutionalization for another," Vallas said.

Another panel member at the briefing, Middlesex County Sheriff Peter Koutoujian, noted the Cook County jail, L.A. County jail, and Rikers Island are the three largest mental health treatment providers in the country.

"The money never followed the people, and additionally, money was cut," Koutoujian said. "Surprise, jails and emergency rooms are now the de facto mental health treatment facilities."

The report says those with physical and mental disabilities face inadequate services at nearly every level of interaction with the criminal justice system, from policing to pre-trial booking to court to jail to reentry into society.

The report highlights cases like that of Christine Stein, a deaf North Dakota woman who was arrested after using a video relay to call 911 to report a suicidal man in her apartment. Unable to understand her, police arrested Stein on suspicion of harming the man. "According to a lawsuit against the Jamestown police department and courts, Stein was denied a sign language interpreter not only during police questioning and booking, but also when she was brought before a judge for court proceedings," the report states. "The charges were ultimately dropped after she was able to meet with an interpreter two days before she was scheduled to return to court."

People who are deaf are sometimes denied access to court interpreters or in other cases billed for them, Vallas said. According to the advocacy group HEARD (Helping Educate to Advance the Rights of the Deaf), deaf people are often held in solitary as a "substitute for the provision of accommodations for and protection of deaf and disabled prisoners."

People with disabilities are more likely to be on the receiving end of police violence, as well. Nearly a quarter of those fatally shot by police in 2015 had some form of mental illness, according to The Washington Post's analysis of fatal police shootings.

In an interview last week, former New Orleans Police Department superintendent Ronal Serpas, who now heads the group Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration, said he had watched this growing trend since he was a rookie officer in the '80s. "Our officers are so removed from fighting violent crime because they're just out there dealing with people who have mental health issues," Serpas said.

Serpas said his officers would complain about the endless cycle of locking up people with mental illness for a day or two at a time, letting them out, and then repeating the whole process a day or two later: "They would tell me, 'Chief, I'm giving this guy a life sentence two days at a time.'"

The Center for American Progress report recommends expanding police training for officers on dealing with people with disabilities, diverting those with disabilities to community-based services, improving court and jail compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and funding more robust reentry programs.

Show Comments (95)