Trump, Clinton, Stein, and Johnson on Drugs

All four presidential candidates say states should be free to legalize marijuana, but they differ on whether that's a good idea.

The last time the Democratic Party's platform mentioned marijuana was in 1984, when it cited "25 million regular abusers of marijuana" and "15,000 tons of marijuana" entering the United States each year as "clear evidence that we are losing the effort overseas to control the production and transshipment of…dangerous drugs." The draft for this year's platform mentions marijuana half a dozen times, and the context is notably different:

We believe that the states should be laboratories of democracy on the issue of marijuana, and those states that want to decriminalize marijuana should be able to do so. We support policies that will allow more research on marijuana, as well as reforming our laws to allow legal marijuana businesses to exist without uncertainty. And we recognize our current marijuana laws have had an unacceptable disparate impact, with arrest rates for marijuana possession among African Americans far outstripping arrest rates among whites, despite similar usage rates.

Assuming something like that language is included in the final version of the platform, the Democrats, after three decades of silence on the subject, have gone from advocating an escalation of the war on weed to facilitating more tolerant approaches, including outright legalization. What's more, every presidential candidate you are likely to see on your ballot this November agrees that states should be free to legalize marijuana—a remarkable development attributable not only to the landmark 2012 initiatives in Colorado and Washington but to a concomitant shift in public opinion nationwide.

Once you get beyond the question of how the federal government should respond to states that legalize marijuana, there are some notable differences on drug policy among the four parties with wide ballot access. Here is a summary of where they stand, arranged from least to most tolerant.

Republican Party

Unlike New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a former rival for the GOP nomination who is now a supporter and potential running mate, Donald Trump has never promised to stop marijuana legalization in its tracks. To the contrary, he says "that should be a state issue," although he also says legalization is a bad idea (albeit one he used to support, not only for marijuana but for other drugs as well).

Marijuana federalism aside, Trump sounds like an unreconstructed drug warrior. "I'm going to create borders," he promises. "No drugs are coming in. We're gonna build a wall. You know what I'm talking about. You have confidence in me. Believe me, I will solve the problem."

That's how most Republicans and many Democrats have been talking about drugs for as long as I can remember: If only we put our minds to it and spend enough money, we can stop the flow of drugs that threatens to turn us into a nation of dope fiends. A century of failure with this approach should have demonstrated its folly even to those unfamiliar with the economics of black markets.

On the question of how to treat Americans who manage to obtain arbitrarily proscribed intoxicants despite the best efforts of border-blocking drug warriors, Trump sounds at least as sympathetic as Richard Nixon. "The people that are in trouble, the people that are addicted, we're going to work with them and try to make them better," he says, "and we will make them better."

Democratic Party

Hillary Clinton is down with "laboratories of democracy," as long as the experiments involve cannabis. "I want to wait and see what the evidence is," she says. Unlike Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator who ran against her in the Democratic primaries, Clinton is not ready to repeal federal prohibition, although she thinks marijuana should be moved from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act to Schedule II, which she says will facilitate medical research.

Clinton's promises regarding addiction treatment are at least as grandiose as Trump's plan to stop drugs at the border. "There are 23 million Americans suffering from addiction," she says. "But no one is untouched. We all have family and friends who are affected. We can't afford to stay on the sidelines any longer—because when families are strong, America is strong. Through improved treatment, prevention, and training, we can end this quiet epidemic once and for all."

Despite her compassionate pose and her support for sentencing reform, Clinton is not forswearing the use of force and violence to discourage drug use. When Clinton says "our state and federal prisons…are no substitute for proper treatment," when she talks about "ensur[ing] every person suffering from addiction can obtain comprehensive treatment" and "prioritiz[ing] treatment over prison for low-level and nonviolent drug offenders," what she has in mind is, at best, giving consumers of politically incorrect intoxicants a choice between a treatment slot and a jail cell.

Although Clinton's addict estimate includes alcoholics, that is not a choice even the heaviest drinker has to confront unless he commits a crime. Drinking itself, unlike the use of illegal drugs, does not qualify. A corollary is that even casual drug users with no addiction to treat may still have to choose between treatment and jail if they happen to get caught.

Clinton does not bother to defend this blatantly unequal approach, because it is indefensible. It is therefore hard to take seriously her pose as an enlightened public servant who only wants to help "sick people that deserve to get well." This medicalization of drug policy may take some of the rough edges off the war on drugs (or not), but only at the cost of denying the moral agency of drug users, which justifies the government's shabby and often brutal treatment of them.

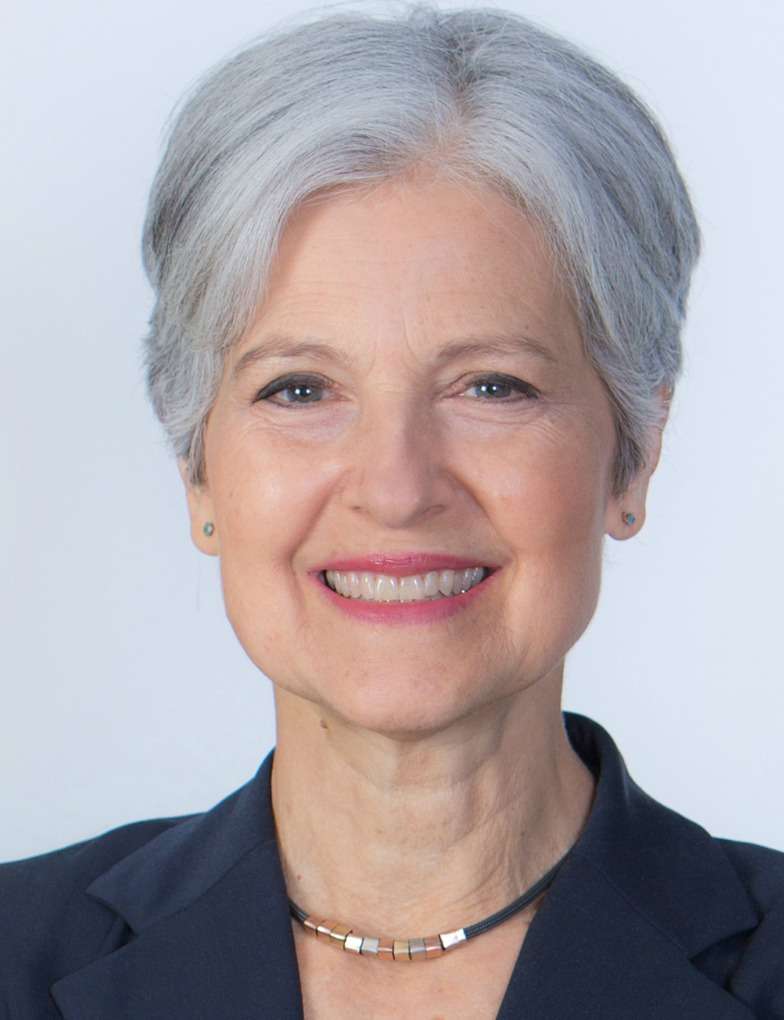

Green Party

Jill Stein, the Green Party's presidential nominee, thinks we should "treat substance abuse as a health problem, not a criminal offense." Yet she also says "we wouldn't remove all laws against all drug use." Still, Stein goes further than Clinton, saying we should "end the failed war on drugs," "replace drug prohibition with harm reduction," and "legalize marijuana/hemp."

The Green Party, which nominated its first presidential candidate (Ralph Nader) in 1996, has opposed criminal penalties for marijuana use since 2000. "It's time to get rid of the black market and bring marijuana sales under a legal regulatory framework," Stein said when she ran for governor of Massachusetts in 2010. "In this way, we can staunch the flow of money to illegal drug networks, generate new funds for our communities, improve public safety, and create new jobs in growing hemp for food and fiber."

Libertarian Party

The Libertarians' position on drug policy is clear: They are against it. The party's platform says, "We favor the repeal of all laws creating 'crimes' without victims, such as the use of drugs for medicinal or recreational purposes." Opposing the criminalization of consensual adult activities covers a lot of ground, and as it relates to psychoactive substances the principle cannot logically be limited to marijuana. Yet Gary Johnson, the former New Mexico governor who was the Libertarian nominee in 2012 and tops the ticket again this year, is trying to do just that.

"We are not espousing the legalization of any drugs outside of marijuana," Johnson, the former CEO of a cannabis company, said during a CNN town hall last month. Pressed about whether he and his running mate, former Massachusetts governor William Weld, want to legalize drugs such as heroin, he said they would "keep the drugs illegal" while trying to reduce the harm caused by prohibition, which sounds similar to Jill Stein's position.

Johnson's campaign website likewise says "Johnson and Weld do not support the legalization of other recreational drugs that are currently illegal." But it also says, referring to the Founders, "Imagine their shock to learn that the government has decided it is appropriate to tell adults what they can put in their bodies." That, of course, is exactly what the government is doing when it "keep[s] the drugs illegal."

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Show Comments (174)