Libertarian History/Philosophy

Libertarianism, Yes! But *What Kind* of Libertarianism?

Virtue vs. Libertinism or, a Reason debate on liberty, license, coercion, and responsibility.

If you've been part of the broad-based libertarian movement for more than a few years, you know that it is growing in popularity, visibility, and influence throughout American politics, culture, and ideas. Once a smallish movement tightly identified with the likes of Ayn Rand, Robert Heinlein, and Milton Friedman, rarely a day goes by now where some new writer, thinker, pundit, artist, or celebrity doesn't come out as libertarian (among the most recent: Jane's Addiction guitarist and TV host Dave Navarro and Republican political consultant Mary Matalin). "Libertarianish" politicians such as Rand Paul, Justin Amash, and Thomas Massie are blazing a different path in the Republican Party and Rand's father Ron electrified college campuses during his runs for the GOP presidential nomination in 2008 and 2012. Two years ago, The New York Times Magazine asked, "Has the 'Libertarian Moment' Finally Arrived?" and in the 2016 election cycle the Libertarian Party presidential ticket of former governors Gary Johnson and William Weld has already probably received more press than all previous tickets did put together.

So libertarianism as a political and cultural force is on the rise. With that in mind, Reason.com is happy to host a debate over "virtue libertarianism." William Ruger, a former college professor and Afghanistan war vet who is now vice president of research and policy at the Charles Koch Institute, and Jason Sorens, a lecturer in the Department of Government at Dartmouth College and the originator of idea behind the Free State Project, argue that libertarianism—"the political philosophy of free markets, property rights, toleration, and peace"—will grow even faster if its champions embrace "a duty to respect our own moral nature and to promote its development in others." In short, they reject what they call "libertine libertarianism," or a willingness to treat all lifestyle choices as essentially morally equivalent. Conservatives and progressives, they say, worry that a libertarian world in which the goverment is reduced to its simple "night watchman" functions will likely result in anarchy or a world in which the poor and defenseless are constantly degraded. Virtue libertarianism assuages these fears, they hold, by providing moral direction that will improve people's outcome and material support for those who can't help themselves. It's not just the right of libertarians to endorse and uphold particular ways of living, they say, it's the duty of libertarians to do so, as long as the state's coercive apparatus is not involved.

This is a provocative thesis, to say the least, and Ruger and Sorens are answered by Steven Horwitz, a self-identified "bleeding-heart libertarian" and a professor of economics at St. Lawrence University; Deirdre McCloskey, who teaches economics, literature and communications at University of Illinois at Chicago and is the author of the new Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World; and Katherine Mangu-Ward, the managing editor of Reason magazine.

Comments can be added below. Send email responses to react@reason.com.—Nick Gillespie, Reason.com.

The Case for 'Virtue Libertarianism' Over Libertinism

William Ruger and Jason Sorens

Over the past several decades, libertarianism—the political philosophy of free markets, property rights, toleration, and peace—has gone mainstream. The libertarian perspective on a wide range of policy issues—including growing support for educational choice, Second Amendment rights, marijuana legalization, and criminal justice reform—has not only become respectable but the one held by a majority of Americans. Liberating technologies at the heart of the "sharing economy" and new forms of money such as Bitcoin are also widely hailed (and demonized!) as libertarian.

While the presidential ambitions of the "libertarianish" Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) were thwarted (at least in this election cycle) and people within and without the movement debate whether what Reason and The New York Times called "The Libertarian Moment" is dead, alive, or completely mythical, Gallup says that the single largest ideological position held among the electorate is in fact libertarian. In its annual governance survey, Gallup uses answers to two questions—one on whether the government should promote traditional values and one on whether government is "trying to do too many things that should be left to businesses and individuals"—to categorize voters into one of four groups. For the first time in decades of asking, libertarians comprised the single-biggest group, with 27 percent of the electorate. They were followed by conservatives (26 percent), liberals (23 percent), and populists (15 percent), while 10 percent fit into no category.

So libertarianism, yes! But what kind of libertarianism?

This question matters because one of the things holding libertarianism back from even-wider acceptance is a real discomfort many conservatives and progressives feel about it. Conservatives fear the movement will precipitate the unmooring of society from its moral anchors. For example, David Brooks of the New York Times fears that marijuana legalization will nurture a "moral ecology" that subverts sound character. Progressives accuse libertarians of believing that the "means justify the ends," thus remaining unacceptably indifferent to poverty and inequality. Do they have good reason to worry? Yes and no. It really depends on what kind of libertarianism prevails.

Libertarians value liberty because it respects the moral dignity of the individual, but there are other duties that advance the moral dignity of the individual as well. Plausibly, we have obligations to others and ourselves that go beyond merely respecting rights, in order to promote or recognize our moral natures.

One kind of libertarianism embraces this view, and one does not—or at least is wildly inconsistent in the application of it.

The latter kind, which we'll call libertine libertarianism, is in its most consistent form radically indifferent to the choices that people make with their freedom. This line of thinking holds that so long as an act is consensual and respects at least one truth—the inviolability of the person's fundamental right to choose how to use his or her person and property—not only should the law not get involved, but there is also no ground for moral criticism of the act. Values are essentially subjective in more than a descriptive sense but in a normative sense as well.

Not long ago, for instance, the internet, including Reason.com, and cable news were buzzing with the story of Belle Knox, a Duke University student who said she'd turned to acting in porn movies to pay for her undergraduate education. From the perspective of a libertine libertarian, anyone who might suggest this young woman was acting improperly is, at best, a prude or a scold, and at worst, a sexist. A coterie of social progressives, some libertarians among them, even aggressively berates anyone who criticizes sexual license as a "slut shamer."

But nothing about political libertarianism implies libertinism. In fact, libertine libertarianism is generally incoherent. For instance, could a libertarian reasonably think it morally permissible to destroy one's own rational nature with heavy drug use? Such acts would corrode the very qualities that make a person worthy of having his rights respected to begin with.

Of course, most libertine libertarians aren't promoting a consistent, thoroughgoing Protagorean relativism—meaning truth being different for every person or even that there is no truth with a capital T. Few people who question others for making moral judgments actually stick to the relativistic position when pressed. But they often advance either a libertarianism with very thin ethical content that comes close to that pure form or a thick variant that takes its cues from more socially (and politically correct) left-wing moral dogma. For instance, we have heard a great deal lately about the libertarian cases against authority in the workplace, for detailed accountings of the different kinds of "privilege" that people belonging to different categories enjoy, and even for living off welfare. Indeed, this form of libertine libertarianism often aggressively deploys weapons of rhetorical condemnation against those who would draw moral distinctions with which they disagree. Their willingness to attribute bad motives like hatred to social conservatives while assuming the mantle of tolerance (in the contemporary sense) is this movement's distinctive form of hypocrisy. In short, many socially progressive libertarians actively attack moral judgment in the name of a competing one.

What we call virtue libertarianism is the alternative to libertinism of the stronger and weaker varieties. Virtue libertarians recognize that we have a duty to respect our own moral nature and to promote its development in others in proportion to the responsibility we have for them. Heavy drug use that destroys one's own moral or rational faculties is inconsistent with that duty. Sexual license, gluttony, and the ancient vice of pleonexia—an excessive desire to acquire material and other goods—can overpower the virtue of self-command, which Adam Smith astutely recognized as the key to all the other virtues. To respect others, we must act beneficently and generously toward them, not just refrain from taking their freedom.

In some cases, this means providing approbation and disapproval of certain choices to foster a culture consistent with human flourishing and a free society. For example, we should applaud those who pursue excellence in education, the arts, and sport as well as those who give their time and money to help their local communities. We should also not be afraid to hold up life-long committed marriage as an ideal for those with children. Harder in our current age, but equally important for a good society, we should not shy away from expressing disapproval of rent-seekers (those who demand special government privileges), those who harm themselves and their families through habitual intoxication or gambling, and those who idle away their time and talents in frivolous pursuits (like those who use video games as more than a diversion but as effectively a way to plug into Nozick's "experience machine" and out of our reality). At the same time, it is best to express any such disapproval prudently and humbly, given our limited ability to know with precision or certainty what the best life is for any individual or for people in general. Sour and imperious judgmentalism can also disrespect others' nature as free, equal, and rational persons.

Virtue libertarians recognize that freedom is a precondition of true virtue. By virtue here, we mean, like Aristotle, the quality of being a reliably good human being, and more specifically, following Kant, adopting the habits and good will conducive to acting justly and rightly. In this respect, we follow some of the founding thinkers of the 20th-century libertarian tradition, such as Albert Jay Nock and Frank Meyer. Meyer, for example, correctly observed that "Unless men are free to be vicious they cannot be virtuous." Obedience that stems primarily from fear of criminal punishment lacks moral value. Criminalization of sin vitiates our "moral fibre," our capacity for self-control and discipline, whereas freedom allows us to exercise and develop these muscles and prevent their deterioration. When we coercively punish someone for a private vice, we fail to respect that person's moral dignity.

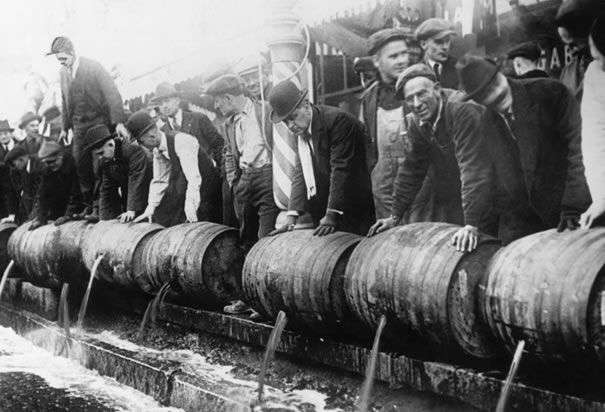

Of course, we are not arguing that the state should be indifferent towards behaviors that violate the rights of others. It is proper for the government to punish those who engage in private coercion such as murder, assault, or theft. Furthermore, prudence suggests that government sanction private behavior that produces or threatens to cause undue significant, direct negative externalities. This is why we think that if someone wants to drink his life away, that should be legal but strongly disapproved or even shunned. However, when the drunk drives his car on a public road, he deserves legal punishment.

Like all libertarians (and distinct from many conservatives and liberals), virtue libertarians advocate treating others as ends in themselves, not simply or primarily as means to some other end, no matter how desirable that end may be.

In short, virtue libertarians think that peaceful means don't justify vicious ends, and also that virtuous ends don't justify coercive means. Prohibitions, SWAT raids, and prison terms for non-violent criminals are all poor ways to grow a healthy moral ecology. Society has better, more-just alternatives. Indeed, what has led to the surge in recent interest in criminal justice reform is precisely a belated recognition among many Americans that mandatory minimum sentences and globe-leading incarceration rates are misguided and disrespect the moral dignity of people.

Rather than seeing government as an "all-purpose fixer" of social problems—which is something that conservatives and liberals tend to do—Americans could rebuild a culture of social approval of virtue and disapproval of vice. They could do so by providing good role models and using the commanding heights of our world—schools, universities, voluntary societies, churches, the media, and the arts—to scorn moral indifference to harmful lifestyles and hold up the values that bring about success and well-being. Virtue libertarians see at least two benefits from this approach. First, it will improve our society. Second, it will reduce the demand for government action. Utah has one of the lowest welfare utilization rates in the country as well as one of the lowest violent crime rates, likely because many Mormons lead responsible lives and can rely on the private safety net of their community and church.

Indeed, it is likely no accident that mutual aid societies, lifelong marriage, and a non-ironic seriousness about the classic virtues flourished in an era when government was more limited. Today's world is better than the past in many respects—less material poverty and greater respect for the rights of women and ethnic, racial, and sexual minorities—but there is still something to be learned from received wisdom. And the idea that certain behaviors and a certain character in the people are more consistent than others with the preservation and security of a free society hasn't been that controversial in our history. Washington and Adams both noted the importance of morality to the success of our system. Our first president noted in his Farewell Address that, "It is substantially true that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule, indeed, extends with more or less force to every species of free government. Who that is a sincere friend to it can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric?"

As others have noted, our economic and intellectual elites still largely practice the sober virtues of a high-capitalist civilization but have lost the confidence or courage to expect those virtues of the whole society. Our society rewards probity in dealings with others, responsibility in child-bearing and rearing, patience, self-control, and generosity toward the less fortunate. As University of Illinois at Chicago economic historian Deirdre McCloskey has found, market economies reward most of these virtues—provided cronyism and corruption are kept within strict bounds. Thus the pursuit of virtue—in tandem with the freedom necessary for its true realization—helps promote both personal and general well-being.

By taking the teaching of these virtues out of the public square, however, we have set up for failure those who, for whatever reason, suffer from greater impulsiveness, hedonism, laziness, hopelessness, or greed. A depressing but fascinating recent front page article in the Washington Post on female health outcomes provides support for our view. It reports evidence of a growing gap between rural and urban white mid-life female mortality rates and finds an elevated rate of death risk for "middle-aged white Americans" that has been impacted by "opioid abuse, heavy drinking, smoking and other self-destructive behaviors."

This dovetails with Charles Murray's 2012 book, Coming Apart, which showed just how far apart the "new upper class" and "new lower class" have become on work ethic, family structure, and more. Another recent study by the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and others reports that "most Americans without college degrees now have their first child before they marry. By contrast, the vast majority of college-educated men and women still put childbearing after marriage." The CDC claims that households headed by an American with a bachelor's degree have more than 50 percent lower child obesity rates than households headed by an American with less than a high school degree. Lower-education adults are also far more likely to smoke cigarettes than college-educated adults. If these socioeconomic divides continue to widen, the cause of liberty will fare badly, as more Americans seek government help for their problems or come to resent the economic inequality that is in part the natural consequence of such differences in virtues that these behavioral differences represent. If a flourishing liberal democracy is to survive, its members must take virtue as seriously as it rightly views consent.

Virtue libertarianism is not simply more philosophically coherent than libertinism, it is almost certainly more politically appealing. Since libertarianism properly understood focuses on both the freedom and moral dignity of individuals that the American experiment traditionally prizes, it should appeal to a large swath of people and transcend partisan lines in a way that conservative and liberal ideologies cannot. Each of those, ultimately, is based upon a belief that the state can and should structure society, even at the cost of personal rights and liberty. Liberals and conservatives often defend limiting a person's choices and growing the state precisely because they believe people are ill-equipped to make such choices and will have no other means of support for help and guidance. In a way that libertine libertarianism does not, virtue libertarianism provides the foundation for a new governing philosophy that energizes society while deemphasizing government.

It will also be a lot easier for elected officials to argue for political forbearance of people's lifestyle choices if they aren't asking for their supporters or the government to embrace them as positive goods. Virtue libertarianism asks people to embrace a vision of official toleration and government minimalism—and to allow for social change and debates about the good life to take place in the rough-and-tumble market of ideas even if that makes some of us uncomfortable with our life choices.

A Kinder and Gentler Form of Victim-Blaming

Steven Horwitz

That I agree with a number of points William Ruger and Jason Sorens make might suggest one of the problems with their argument: The position they are arguing against is not one held by any significant number of libertarians, especially not by any libertarians exercising real influence over what libertarianism means. Although they have not necessarily created a straw libertarian to knock over, they have taken bits and pieces of the actual views of a very small number of libertarians and tried to construct a coherent perspective out of them. Not surprisingly, they then show that the resulting view isn't very coherent, and their alternative libertarianism risks worsening the problem they believe they are solving. Theirs is a weak argument against a largely non-existent opponent.

Of the four links to the views of the so-called libertine libertarians, two point to the blog posts of one author who is not clearly a libertarian, a third points to a student essay, and the fourth offers an argument far more nuanced than Ruger and Sorens suggest.

What's worse is that then Ruger and Sorens engage in a little bait-and-switch that leaves the argument they oppose looking nearly identical to Ray Bolger. After suggesting via those original links that libertine libertarians hold a whole bunch of (to them, problematic) socially progressive views, we are told how virtue libertarians, by contrast, believe that we need to applaud human excellence, express our disapproval of rent-seekers, and "hold up life-long committed marriage as an ideal for those with children." They do so without providing evidence of any supposed "libertine libertarians" arguing against any of those propositions. Rather, by innuendo, they suggest that the writers linked to earlier also reject those beliefs.

My first reaction to the list in the prior paragraph is that it's the libertarian equivalent of mom and apple pie. Where are the links to libertarian public intellectuals tearing down human excellence or praising rent-seekers? As someone who has argued that the flowering of a variety of family forms over the last few decades is not nearly as dire a problem as social conservatives would have it, I have no disagreement with the claim that "life-long committed marriage" is the ideal context for parenthood.

It's here where my main problem with their argument arises. Ruger and Sorens are careful, thankfully, to say that we should express our disapproval "prudently and humbly" given our limited knowledge about what is the best life for others. Indeed so. But this seems to cut against the whole tenor of their argument. If they wish to claim the higher ground for "virtue," and write with much confidence that they know what constitutes virtue, then why shy away? Or if you are going to acknowledge that context matters, what is the point of arguing for strong blanket concepts of virtue?

For example, a young woman who chooses to have a large number of sexual partners could be throwing all caution to the wind and behaving in ways that we might rightly criticize. It could also be the case that she's very much in control of her own faculties and has engaged in all sorts of precautions to prevent pregnancy and disease, and just happens, heaven forbid, to really enjoy sex. Or perhaps she has some sort of psychological or physical compulsion beyond her conscious control. Are we so sure that this woman's actions demonstrate a (complete) lack of supposed virtue?

Similarly, if Belle Knox made her decision to enter the sex industry in full control of her rational powers—perhaps because she valued her college education enough to want to find a way to pay for it herself—are we so sure that her choices lack virtue, or are rightly to be disapproved of? Would Ruger and Sorens prefer that she had instead lived on the dole of federal student loans, or that she sacrificed her attempt to achieve "excellence in education" by attending an affordable but less-challenging school?

Finally, even as we hold up life-long marriage (whether same-sex or heterosexual, I would add) as our ideal, we need to recognize that real-world contexts matter. Faced with a couple choosing to divorce because they recognize that their constant conflict is harming their kids, what do we say? Prudence and humility in expressing our disapproval of divorce is not enough. If virtue means anything, we should praise that couple for recognizing that it's silly to fetishize an abstract virtue over the very concrete virtue of doing right by their children.

Yes, it's both easy and wrong, as Ruger and Sorens note, to engage in "sour and imperious judgmentalism," but wrapping ourselves in the language of virtue will not make such un-virtuous behavior less likely. Judging virtue is almost always going to require the sort of contextual knowledge that is obliterated by unconditional statements of what behaviors count as virtuous no matter how prudently and humbly we judge.

Even though Ruger and Sorens clearly reject a role for the state in enforcing their conception of virtue, their desire to make libertarianism more friendly to liberals and conservatives alike by adopting the language of virtue runs the risk of inviting those with less forbearance into the big tent. Historically, virtue-talk of the judgmental sort they are engaging in has often been the foundation for state intervention.

Rather than infusing libertarianism with the language of virtue and moral condemnation to eliminate a problematic flavor of libertarianism that doesn't really exist, we should be more strongly emphasizing the way government makes it harder for good people to make good choices. The war on drugs, tax and welfare policies affecting marriage and divorce, and labor laws that reduce employment especially among the young: These all create an environment more conducive to choices that Ruger and Sorens would condemn. Encouraging us to do more of what often sounds like a polite version of victim-blaming is neither an effective nor especially virtuous way to bring about a more virtuous libertarianism, a more virtuous society, or more libertarianism.

Christian Libertarianism Is What Our Politics Needs

Deirdre Nansen McCloskey

Yes. "Virtue libertarianism" is a good phrase and a good idea. Some call it "bleeding-heart" libertarianism, and I call it "motherly" or "Christian" (or Jewish or Hindu or Islamic) libertarianism. It is a true liberalism that acknowledges a responsibility to the poor, but notes that making them into serfs of the state is not a good way of fulfilling the responsibility.

At a conference of many hundreds of libertarians in Barbados a while ago I remarked to a man I had not formerly met, by way of expressing a sacred duty we libertarians of course all acknowledged, "We must help the poor." He instantly shot back—it was like being punched in the stomach—"Only if they help me." His libertarianism was fatherly. But there is a motherly version available, in which children are instructed to be ethical human beings in both the trading and the non-trading parts of their lives. We realize that we best help the poor by making them un-poor in a dynamic economy freed from idiotic and poor-impoverishing regulations.

Virtue libertarianism is probably what most Americans really want, and possibly even on November 8. Let us pray they do, but pray also that the election does not therefore get thrown into the House of Representatives, where fatherly libertarians are about the best we can expect. Mostly the GOP Republicans are statists, happy to intrude on bedrooms and happy to give out corporate welfare. Good lord, they are no better than Hillary Clinton.

Virtue or Christian libertarianism can be the basis for a new party gathering up the ruined Republicans and the depressed Democrats. Maybe, just maybe, such a party can wean our fellow citizens from the statist Bismarckian plan. As Count Bismarck in retirement said, "My idea was to bribe the working classes—or shall I say, to win them over?—to regard the state as a social institution, existing for their sake and interested in their welfare." As he put it in a speech in 1889, "I will consider it a great advantage when we have 700,000 small pensioners [then nearly the entire population over age 60 in the German Empire] drawing their annuities from the state, especially if they belong to those classes who otherwise do not have much to lose by an upheaval." He meant, for example, an upheaval against monarchy or in favor of the Social Democrats or against Bismarck's plans for peace in Europe.

It's not going to be easy, the weaning, because the welfare state arose pretty much inevitably from the relatively mass voting introduced in 1867 in Prussia and in the same year in the United Kingdom, and earlier in the United States. As Mencken said, democracy is "the theory that the common people know what they want and deserve to get it, good and hard." Consult Venezuela or Argentina, or indeed President Trump. People have since the 1930s got used to the idea that every trouble is the state's fault … for not doing enough. Watch what happens in the opioid epidemic—more proposals for more prohibition enforced by the Drug Enforcement Agency with more powers.

Certainly a flourishing society and even an economy needs ethics. That's what I learned from writing over the past decade and a half the three volumes of The Bourgeois Era. I realized, against my economic training, that incentives are not enough. Neo-institutionalism in economics, for example, is a rehash of the incentive-mad policies of American Progressivism or British Fabianism, with their infantilization of adults. So too is behavioral economics and its associated politics of state "nudging." My friend Bob Frank tries to soften me up by declaring nudging to be "paternalistic libertarianism." Oh, swell.

The ethical basis for a flourishing society, Ruger and Sorens say, and I agree, cannot be provided by an intrusive state. When states like East Germany or state-like institutions such as the Catholic church in Ireland have attempted it, it has failed. Ruger and Sorens agree that even nominally liberal societies such as our own, or Britain, decay when they leave ethical judgment to the state, or leave it aside altogether.

But when people hear the word "ethics" they think "preaching," and react as atheists do. That is because they have a childish idea of ethical theory, such as "positive/normative" in economic teaching, or the Baltimore Catechism and the nuns to enforce it. (And, by the way, the atheists have also a childish idea of theology: Jerry Falwell pure and simple.)

I would only ask Ruger and Sorens that they get serious and adult about ethical theory and ethical practice. And theology. Neither Kant nor Bentham nor Locke are good guides. What is good is the ancient and worldwide and commonsensical theory of "virtue ethics." It is the sort the Blessed Adam Smith advocated, namely, reflection on a handful of named and principal virtues, each backed by a library of books. In Smith's case they were five-and-a-half: prudence, temperance, justice, and, with less approval, the fourth classical virtue, courage and the secular part of Christian love. In Aquinas's case, and in that of the massive study of positive psychology Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification (2004), edited by Christopher Peterson and Martin E. P. Seligman, they are seven: a jury-rigged melding of the classical four and the Christian three (with hope and faith, that is, having a project and seeking transcendents, such as baseball or God). Some such list is paralleled in every ethical tradition from Confucius to the Mahabharata.

Stories are the keys to an ethical kingdom, and economy. The Christian Libertarian Party would need to encourage, as Fred Smith of the Competitive Enterprise Institute wishes, novels, poems, rock music, movies, country music that do more than attack yet again the wretched bourgeoisie.

To put it another way, the ruling theory of virtue libertarianism should be, as Bart Wilson and the Nobelist Vernon Smith put it, a "humanomics," which is incentive economics plus human stories. It doesn't give up science. On the contrary, it is is the best scientific explanation of how we got rich, 1800 to the present, and how the whole world soon will.

Just Say No to the Libertarian Vice Squad

Katherine Mangu-Ward

For a couple of guys who praise humility and colorfully condemn "sour and imperious judgmentalism," my good friends William Ruger and Jason Sorens have an awfully specific list of vices they'd like to wipe out. These include, but are not limited to: acting in porn to pay for college, breeders breaking their marriage vows, habitual intoxication and gambling, rent-seeking, and idling away time with escapist video games.

Full disclosure: That list looks rather uncontroversial to my eyes. I suspect many of my fellow libertarians would agree. That's what makes it so dangerous.

Libertarianism is the system in which virtuous behavior is mostly likely to flourish, for precisely the reasons Ruger and Sorens so eloquently explain—virtue not freely chosen is no virtue at all. Charity given at the point of a gun isn't praiseworthy, and "prohibitions, SWAT raids, and prison terms for non-violent criminals are all poor ways to grow a healthy moral ecology." Amen, brothers.

Yet all is not well, write Ruger and Sorens. The empty spaces left by the minimal state should brim with the cool waters of virtue, but instead become clogged with the unsanitary hot-tub dregs of libertinism.

The solution: It's time to rig the "rough-and-tumble market of ideas" in favor of virtue using a moral cartel of "schools, universities, voluntary societies, churches, the media, and the arts."

Ruger and Sorens are careful to make clear that the business of the state and the business of these busybodies shouldn't overlap. They're correct: For the same reasons that libertarians almost universally agree that government bureaucrats should not pick winners when it comes to the manufacturers of solar panels or jumbo jets, the state should also not be empowered to hand out sashes (or scholarships) in the Miss Virtue pageant. A thumb on the scale stifles innovation and discourages experimentation. It locks in the status quo.

The same thing can and does happen in the moral realm. Despite what Ruger and Sorens suggest, a list of virtues suited to a free society—and perhaps more importantly, our ability to identify those virtues in the wild—is historically contingent and tricky to pin down.

What looks like vice in a static era (risk-taking, the accumulation of debt) could be virtue in a dynamic one. What looks like virtue in a martial, zero-sum society (extreme physical courage, unquestioning loyalty) can become vice in world of peace and markets.

Just take a peek at the writings John Stuart Mill, one of the wokest, most forward-thinking gents of 19th century, on the duty of the British colonialist "despots" to help "barbarians" develop their capacity for self government. Then read Ruger and Sorens on "the economic and intellectual elites" who "have lost the confidence or courage to expect those virtues of the whole society," and in so doing "have set up for failure those who, for whatever reason, suffer from greater impulsiveness, laziness, hopelessness, or greed." Sound familiar? The comparison to Mill is a compliment—but even the best, most generous thinkers can stumble.

Despite accurately diagnosing the folly of smuggling lefty values of political correctness and egalitarianism into libertarianism, Ruger and Sorens then turn around and do their best impression of Cinderella's stepsisters, trying to shove their lumpy, oversized moral philosophy into the elegant glass slipper of libertarianism, with unnecessarily bloody results.

Instead of adhering to a "thin," or pluralist, conception of libertarianism with room for many ways of being inside it, Ruger and Sorens have appointed themselves to the vice squad—it's no coincidence that their discussion keeps circling back to sex and drugs—with the project of saving libertarianism from itself. Meanwhile, the bleeding-heart libertarians have appointed themselves a kind of "nice squad," with the same goal and attendant contradictions.

Ruger and Sorens are on a mission to make libertarianism more palatable—to minimize the "discomfort" conservatives and progressives feel toward the political philosophy of "free markets, property rights, and toleration, and peace." It's not clear why this is a priority if, as they say, there really are oodles of would-be libertarians out there just waiting for labeling and bundling by pollsters and pols.

But if their brand of virtue rhetoric wins approval for libertarianism, it will be precisely because the public cheerfully elides the distinction the authors so laboriously make between the mandatory and the laudatory. "Oh!" John Q. Public will say. "These libertarian fellows want everyone to get married and stop doing drugs? Well that's alright then; let them in to the mainstream political discourse and pour them a beer!"

Ruger and Sorens play with this confusion, tossing around the words "we" and "the public" in ambiguous ways. "Government," as Barney Frank almost certainly didn't say, "is simply the name we give to the things we choose to do together" after all. Ruger and Sorens do not believe this, but they're trying to make common cause with those who do—to convince right- and left-wing moralists and libertarians that they can have their cake and eat it too. It won't end well. It never does.

Luckily, there's an alternative. No need for a massive coordinated campaign on behalf of one conception of virtue. Instead, let people with different ideas about the intersection of virtue and politics experiment with their own visions, in a variant on Robert Nozick's framework for utopia. Interested in a real world example of how that might play out? There's always the Free State Project, in which 20,000 libertarians propose to move their homebrew setups, dog-eared copies of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and Xboxes to New Hampshire in order to develop proof-of-concept for the power of limited government—following an outline sketched in a rather brilliant 2001 article by none other than Jason Sorens.

Liberty and Virtue: A Final Reply

William Ruger & Jason Sorens

We argue in favor of virtue libertarianism, which marries political libertarianism (the law of maximum equal freedom) to a concern for robust moral duties, both positive and negative, that go beyond mere respect for freedom. Libertine libertarianism of both the stronger and weaker varieties is logically incoherent, because it simultaneously demands respect for rights but expresses indifference about the very foundations of those rights. Virtue libertarianism has much to offer American society now, both in attracting more people to the libertarian standard and in addressing numerous social ills.

All three commenters on our piece make important points, and we are grateful for their efforts. But we would like to discuss some of their claims. Unfortunately, space limitations do not allow us to respond to each point or in sufficient depth.

In response to Deirdre McCloskey's fruitful contribution, we are tempted to simply triple down on what she writes at the outset of her piece by saying "Yes, yes, yes." But we'll try to resist that temptation in the spirit of further engagement with someone whose work we so admire.

Like her, we would enjoy seeing virtue libertarianism—by this or any other name—become the basis of a new majority approach to our politics and ethics. It is absolutely critical for our country at least to move in that direction. Libertinism of the stronger and weaker varieties we discuss in our original essay leads to enough problematic behaviors and results that it undermines support for freedom. Moreover, it would allow latter-day Bismarcks—or worse—to take advantage of a populace without certain virtues necessary for the health and life of a liberal democracy. There is little doubt that Bruce Yandle's power-hungry bootleggers and well-intentioned Baptists will take advantage of things like the opioid crisis McCloskey mentions to maintain and grow the state while reducing the sphere of liberty. Crises like these spring from our all-too-common human failings but also our inability to create a moral ecology that smooths our rougher edges.

We also agree that Smith and Aquinas have a lot to add to our theory and practice, though we do not see them as necessarily inconsistent with the best in thinkers like Kant and Locke. We'd add the great Aristotle too, not to mention Eastern traditions that parallel these thinkers. These theories can inform the kinds of storytelling necessary to build and buttress an ethical society. Authors from Plutarch to Austen to Dostoyevsky explore and reveal the role that moral ideas and virtues play in influencing our acts and their effects on others.

We appreciate Horwitz's and Mangu-Ward's thoughtful contributions as well. Both share concern about virtue libertarianism and our criticism of libertine libertarianism on the grounds that our arguments are at different points dangerous, wrong, or trivial.

One of Horwitz's critiques is that "virtue-talk of the judgmental sort…has often been the foundation of state intervention." Thus it is dangerous. Mangu-Ward similarly worries that "virtue rhetoric" will attract "right- and left-wing moralists" into the libertarian tent, which "won't end well." The specific claim here is not that virtue libertarianism is wrong per se but that it is just too dangerous an idea to promote. The claim is eerily similar to police lobbyists' old chestnut that legalizing pot is bad because it "sends the wrong message to children." Both arguments hold that liberty and virtue are incompatible—if not conceptually, then in terms of how it will all play out politically. We believe that, to the contrary, people can understand that liberty and virtue have value at the same time, and that in fact liberty with libertinism is no stable equilibrium.

We also worry that most Americans, if forced to choose between liberty for all and their preferred form of morality, will reject liberty. We make liberty more attractive when we show our sincere respect for the ends others want to achieve. McCloskey's anecdote about "fatherly libertarians" is a great example. Many libertarians are willing to concede that if welfare is cut or abolished, people will still give to anti-poverty efforts voluntarily. But this just isn't enough to reassure those with strongly egalitarian moral commitments, who are willing to sacrifice freedom as necessary to achieve their ends. Libertarians can do better by standing shoulder to shoulder with the bleeding hearts in saying that there is a moral duty to help those in dire need, and we will promote greater private efforts to help them even as we try to remove force from the equation.

Horwitz argues that virtue libertarianism, in addition to being dangerous, is unnecessary because few people hold the libertine libertarian position we criticize, and most of what we endorse is actually as widely acclaimed as apple pie. Yet Horwitz himself has come down on young libertarian personality Julie Borowski for "slut shaming," seemingly defined as criticizing the vapidity of popular women's magazines. Furthermore, as virtue libertarians who have attempted one form or another of this argument in a variety of venues, we've seen first-hand the subjectivist, relativist, and/or socially leftist responses of people who identify as libertarians. While there are certainly a lot of virtue libertarians out there (though some may feel lonely or sheepish in conversations with other libertarians that turn to ethical issues), we have a hard time believing that we aren't seeing something real that people who have been in the libertarian ecosystem would recognize. There is a reason why libertarians have the unfortunate reputation of focusing on drugs and sex. It didn't come out of nowhere. Anyone could read the pages of Reason magazine or watch the Libertarian Party convention to see that virtue talk is rare and radical choices celebrated. And while some senior libertarian elites may be less prone to libertinism, many of them come close to arguing against all traditional social constraints on the expression and realization of individual preferences, not just coercive ones.

Finally, Horwitz says we cannot have it both ways. We should either go for it and be Mangu-Ward's "vice squad," judging everyone for everything, or shy away from moral judgment altogether. Thus, we can't, while recognizing humility, judge Belle Knox's choice to do porn to fund college, because there might be some circumstances that justify her decision. While context certainly can make the difference in many cases, we shouldn't let exceptions swallow the rule. As a rule, acting in porn trades one's dignity for money. Ms. Knox was no Jean Valjean operating in extremis. She was merely trying to pay for an elite private education, a noble end but not one justifying any means whatever. Purely recreational or commercial sex skews the important pair-bonding, psychological functions of sex and can risk one's self-respect, not to mention overall flourishing. Again, Horwitz's approach to this case shows that we aren't up against a strawman. Anyone who would rationalize these actions embraces a very different worldview from ours and from the time-tested perspectives of mainstream ethical thought.

We might ask ourselves how far we should take Horwitz's position against "unconditional statements of what behaviors count as virtuous." Can we not judge the person who yells racial epithets? How about the person who engages in voluntary cannibalism (as we saw in Germany)?

Lastly, it's difficult to know what to make of Horwitz's claim that moral judgment constitutes "victim-blaming." Was Adam Smith blaming victims when he defended moral approbation and disapprobation in a free society? Who are the victims? By whom are they victimized? We would not blame the victims of government coercion. At the same time, we recognize that there are natural and appropriate consequences for irresponsible or antisocial behavior, and those consequences may include losing the society or esteem of one's former friends and associates. That's not victimization.

As for some of the other points in Mangu-Ward's smartly written and enjoyable response, she compares virtue libertarians to bleeding-heart libertarians in trying to "save libertarianism from itself." But unlike some strains of bleeding-heart libertarianism, virtue libertarianism doesn't detract a jot from the libertarianism. We're just trying to add something new that is in no way inconsistent with the original. Rather than watering down Uncle Murray's 200-proof libertarian Everclear, virtue libertarianism adds delicious new liqueurs to the cocktail. (Or if your libertarianism is more Uncle Miltie's 90-proof blend, we do the same to it. Choose your metaphor accordingly.)

Finally, Mangu-Ward writes that we should leave virtue up to the pluralist market of ideas. But we are participants in that very market! The market only works when someone believes the market is currently missing out on a new opportunity. Every successful business strives for market share. Mangu-Ward's suggestion to give up persuading others to a particular conception of virtue is rather like telling a CEO to stop recruiting new customers because "the market will handle it." But she is right that virtue can be tricky to pin down or apply, though we shouldn't give up the effort or think that enduring wisdoms aren't useful guides.

In closing, virtue libertarianism is a house with many rooms. There is plenty of space for debate on where the boundaries of particular moral principles and virtues lie. But to have a serious debate on these questions, we libertarians must first learn to take the idea of virtue seriously.

Show Comments (200)