Why Obama's New Overtime Regs Will Hurt More Than They Help

Get ready for fewer hours, fewer jobs, and more moonlighting. When labor costs increase, employers buy less of it.

The Obama administration's updating of federal policy toward employees covered under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) has been finalized. Starting in December, over 4 million workers who make up to $913 a week ($47,476 per year) will be have to be offered overtime pay (at least time-and-a-half) when they clock in more than 40 hours a week. The old standard was $23,360, so this is essentially a doubling of the threshold. To get a sense of who is covered by the FLSA, go here.

Guess who likes this sort of edict?

This long overdue change in overtime rules is a step in the right direction and good news for millions of workers. https://t.co/E4uVZJ1ZkT

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) May 18, 2016

No surprise there, but remember that Sanders somehow believes "a choice of 23 underarm spray deodorants" is somehow connected to children going hungry in America.

The White House argues that making labor more expensive will lead not to less demand for it but a surge in middle-class incomes:

Increasing overtime protections is another step in the President's effort to grow and strengthen the middle class by raising Americans' wages. This extra income will not only mean a better life for American families impacted by overtime protections, but will boost our economy across the board as these families spend their hard-earned wages.

This sort of thinking obviously appeals to many people, but it's simply wrong. It presumes that wages are simply set by the whimsy (or more likely, the stinginess) of the employer, who always wants to screw his workers rather than keep them happy. There is always play in the labor market, with some people being overpaid and some being underpaid. But by and large, labor markets do a pretty good job of setting compensation levels that reflect a given worker's skills and value to firms, while also pricing in the ability of companies to cover costs and thus stay in business. Price-fixing, whether it's for good or for labor, interferes with the way that prices allocate resources and reflect supply and demand across an almost infinite number of dimensions. This isn't to claim markets are perfect, but they do a far-better job of pricing relative value than any bureaucrat can do—or for that matter, any bean counter in management at a given firm.

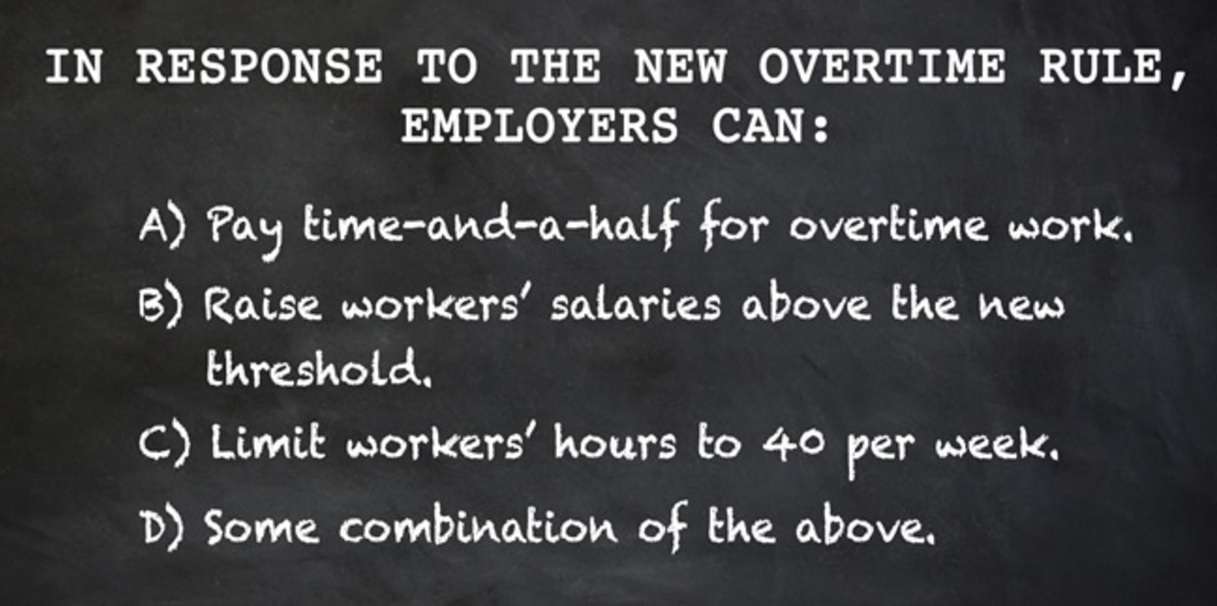

As with the minimum wage, simply jacking up overtime benefits for workers via government edict will have the effect of shrinking demand for labor. Strangely, even the government kind of understands that. Here's what Obama's Department of Labor figures might happen as a result of its latest intervention:

When you look at these possibilities, only A) represents an unambiguously good outcome for workers. But that presumes that employers won't factor in the new costs. It also presumes that employers aren't already offering extra compensation for workers who put in long hours, which could range from spot bonuses to raises to extra vacation or flexible hours or the like. While it's unlikely that a company paying somebody $30,000 will jack her salary to $47,500 to avoid the overtime regs, it's also clear than nudging someone from, say $47,000, will not really help workers very much at the grocery store. And assuming everything stays the same (ceteris paribus) if companies start limiting hours to avoid overtime, it's not as if firms have extra money laying around to hire new workers. Instead, they're likely to reduce services and products to customers and/or reduce other forms of compensation to employees.

This isn't simply theory. In a new study for the Mercatus Center, economists Donald J. Boudreaux and Liya Palagashvili find that "there is neither theoretical nor empirical support that the proposed regulation will meet its stated objectives; in fact, evidence suggests that moonlighting may increase in response to regulations."

The study looks at the various objectives that the government expects the regulations to create (higher pay, higher employment levels, better health, etc.) and finds each of them wanting in light of empirical research. Here's part of the take on how overtime regs work to increase moonlighting:

[Economist Jane] Friesen finds that in Canada a reduction in standard hours has promoted work sharing but that the effect is meaningless because it actually led to moonlighting—workers taking a parttime second job. Specifically, Friesen (2001, 708) finds that "an increase in the predicted probability that a covered worker moonlights of 1.1 percentage points when standard hours [are] decreased from 44 to 40 h, and by 3.2 percentage points when standard hours [are] decreased from 48 to 40 h." Friesen (2001, 710) concludes, "To the extent that overtime pay regulation is successful at spreading work over a larger number of jobs, it is less successful at spreading it over a larger number of workers….These results are less supportive than previous research of the notion that overtime pay regulation might be an effective means of creating employment opportunities for a larger number of workers."

As with large increases in the minimum wage, to the extent that such regulations stay in force, they also prompt "investment in capital," A.K.A. automation.

The new rules are part and parcel of an administration that really seems to be wilfully naive or ignorant of basic economics. If we are in fact living through a new era of low economic growth (of, say, 2 percent annual growth rather than the post-war average of 3 percent), it's folly to think the next step is to cost more and more benefits onto employers. Given the deluge of massive regulation of the economy in the 21st century, egregious spending increases, mounting debt, and state-created uncertainty—and recall, George W. Bush was as bad or worse than Obama on all these scores—is it any wonder that the economy is putt-putting along rather than roaring down the highway?

If the government wants to unilaterally raise living standards, it would be far less disruptive to the labor market and economy to send checks to workers and residents it thinks don't make enough money. But that of course would be difficult to justify politically or, horrors, it might mean the government would have to stop spending money on something else to pay for those transfers. Instead, it keeps choosing to layer more and more requirements on the very businessess that provide jobs to begin with.

Reason TV recently spoke to one of the study's authors, Don Boudreaux, about why doubling the minimum wage to $15 an hour will hurt low-skilled workers most of all:

Show Comments (155)