Venezuela Spends Millions on Incredibly Dumb Things While Its Economy Collapses

Bolivarian socialism apparently means financing things like lousy race-car drivers while the people lack medicine, food, and toilet paper.

Venezuela is on the verge of both economic and social collapse, and the Bolivarian socialist government headed by President Nicolás Maduro is lashing out at any everyone from "whingeing" factory owners (who lack the raw materials they need to produce anything of value) to the U.S. government, who he accused of formenting a coup when he extended the nation's state of emergency last Friday.

The style of socialism introduced to the oil-rich country by Maduro's predecessor, the late Hugo Chavez, was credited by Salon's David Sirota with creating an economic miracle as recently as 2013. But the disaster currently unfolding is more than just a failure of socialism.

Venezuela has been spending a fortune on unnecessary and ridiculous expenditures for years. That is, when government officials haven't been (allegedly) stealing billions in oil profits and pocketing the cash outright.

Despite sitting on the world's largest oil reserves and having nationalized oil production, Venezuela spends $45 million a year on Pastor Maldonado — an undistinguished Formula One race car driver with a predilection for crashing a lot — who essentially serves as a walking billboard for the country's oil company. Wasting taxpayer money on sponsoring a loser athlete is bad enough, but what could possibly be the justification for spending that kind of cash to advertise the national oil company, which by definition has no competition?

The waste and graft surrounding sports doesn't end with Maldonado. Formula Freak reports that following Chavez's death in 2013, "Alejandra Benitez, the Venezuelan minister of sports, found that her falsified signature had moved over 65 million in sporting-fund dollars to places in which it did not belong."

In 2007, as part of Chavez's ambition to "combat American cultural hegemony," he forked over nearly $18 million for "scripts, production costs, wardrobe, lighting, transport, makeup and the creation of the whole creative and administrative platform" of a prospective Danny Glover-helmed film project about a Haitian slave revolt. The film never went into production.

Pro-free market types enjoyed a good laugh when the country's largest beer company ceased production last month, as a direct result of a lack of access to foreign currency and a domestic currency now more useful as toilet paper than legal tender, but the situation in Venezuela grows more tragic by the day.

Though supermarket shelves are pretty much empty these days, for the past two years the government has been fingerprinting shoppers to prevent "hoarding," which itself was also made illegal. As could be completely expected by such scarcity of basic items needed to live, much less live in any semblance of comfort, Bolivarian socialism has spawned a thriving black market.

"In a system that mirrors the rationing implemented across communist countries last century," Andrew Rosati writes in Bloomberg, "Venezuelans are allotted certain days of the week that they can purchase goods deemed most essential by the government." The hole in the marketplace is now filled by entrepreneurs known as bachaqueros, who in turn "have developed their own ecosystem, rules and regulations."

Though Maduro would classify any unauthorized transaction as emblematic of the "economic war" he imagines himself fighting, the economic realities his movement has created have led to "Doctors and accountants moonlight[ing] as cooks at restaurants" and everyday survival the only matter of concern to the populace.

Electricity has been rationed and the workweek has been cut to two days. The government, never known for its tolerance for dissent dating back to Chavez's earliest days in office, recently tried to get a U.S. court to shut own a website advertising favorable exchange rates in towns along the Colombia-Venezuela border.

In The Wall Street Journal, Mary O'Grady wrote of how the hunger of the Venezuelan people can be directly pinned on the arrogance and incompetence of the government:

Chávez confiscated the country's most-productive farms and turned them over to chavistas who don't know how to farm. Even on farms that were not seized, planting is diminished. Most seeds used in Venezuela are imported and without dollars cannot be had. Farmers are reluctant to plant when the costs are high and the harvests are price-controlled. Dairy farms are also less productive now that daily power outages shut down electricity-powered milking machines. Trucks carrying food cargo are often hijacked.

Venezuela has had "free health care for all" since 1999, and has long relied on imported Cuban doctors to make good on that promise to the people, but these days basic medical items like gloves, soap, and intravenous fluids are nearly impossible to come by, to say nothing of medicine and equipment such as X-Ray and dialysis machines.

China will likely help Venezuela stay afloat during its self-created inflation crisis with a $5 billion loan, but with babies dying for lack of basic medical care, riots and looting born of sheer desperation, and the very real and growing risk of a military coup, stability may be a luxury Venezuela can't afford for a long time to come.

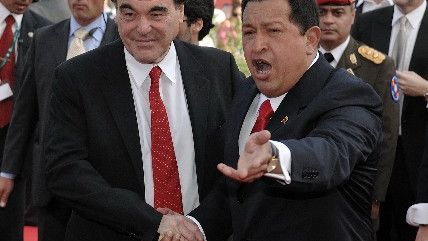

In 2013, Mark Weisbrot (the co-writer of the Oliver Stone-directed Hugo Chavez hagiography South of the Border) wrote in The Guardian that "Venezuela has sufficient reserves and foreign exchange earnings to do whatever it wants, including driving down the black market value of the dollar and eliminating most shortages. These are problems that can be resolved relatively quickly with policy changes."

In a recent article in The Atlantic by Moises Naim and Francisco Toro, the story of an unnamed Venezuelan factory owner — besieged on all sides — demonstrates the silliness and naivete of Weisbrot's assertion that any of Venezuela's problems could be "resolved relatively quickly."

The factory owner is bound by a collective bargaining agreement with his union employees to keep the factory stocked with toilet paper lest he face a strike and the seizure of his factory by the government. But whenever he was able to supply the plant with toilet paper, his workers would steal it and take it home. So the factory owner resorted to the black market, only to have the secret police uncover his stashed toilet paper and accuse him of hoarding.

It wasn't a completely unhappy ending for the factory owner, he was able to avoid jail with a bribe to the police of "a few tens of thousands of dollars," negotiating down from an opening demand in the "high hundreds of thousands of dollars."

But few in Venezuela have the means of this factory owner, and untangling this tragic mess of corruption, artificial scarcity, poverty, violence, and illness will not be "resolved relatively quickly."

Show Comments (108)