D.C.'s Streetcar Nightmare

An outdated transit idea that just keeps coming back.

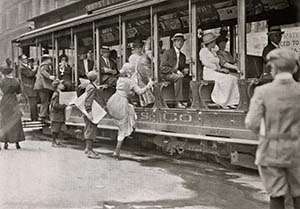

"There's not a single redeeming thing that can be said about streetcars," opined the Washington Post editorial board in 1962. Thankfully, this "hopeless anachronism" in America's capital city had just "clunked its last." Streetcars were beset by technical and logistical flaws that made daily commutes invariably unpleasant, so overwhelmingly Washingtonians were happy to see them go. That's according to the new book, Capital Streetcars: Early Mass Transit in Washington, D.C., by the local historian John DeFerrari.

Naturally, the bastion of efficiency that is the District of Columbia decided to bring the streetcars back, introducing a new 2.2-mile surface-level rail line to run along H Street. Plagued by accidents and engineering problems, the project suffered cost overruns that lifted the price tag to more than $200 million. Initially slated to open in 2012, the new streetcar line finally started offering (fairly limited) service this February—a mere four years behind schedule.

As the late former Mayor Marion Barry put it in 2014, the streetcar "was ill-planned, ill-thought-out, ill-engineered, ill-everything."

Had officials paid more attention to the history, they might have foreseen this outcome. For about a century, streetcars crisscrossed Washington. Though they were an important technology in their time, spurring the development of the commuter suburbs in Virginia and Maryland, streetcars involved major engineering headaches and required an enormous amount of capital investment and maintenance.

"They were very expensive to build," DeFerrari says, "and if you had a new suburb just getting started, you would have very few people there to begin with taking the cars, and the streetcar line would tend to not make money."

In the winter, the rail beds were prone to getting jammed with snow and ice. And when a streetcar got stuck, the entire line would grind to a halt until the problem was resolved.

In 1921, the Washington Rapid Transit Company began running buses alongside the streetcars. Not only were they less vulnerable to breakdowns, but they also moved a lot faster.

"These days we don't think of buses as being terribly sophisticated or exciting," says DeFerrari. "But in 1921 they were. The buses were seen as this fabulous new technology. The streetcars would be trundling along at a fixed speed—usually about 10 miles an hour or so.…And here were these sleek new modern buses with the rubber tires, going freely along the road, nimble and quiet and comfortable and just so much better than the old-fashioned streetcar."

Riders along D.C.'s Connecticut Avenue demonstrated their preference for this superior mode of transit by paying a premium to take the bus.

The new crop of streetcars that recently arrived in the nation's capital have to deal with a new kind of problem. Historically, rails were laid down the center of the street to avoid traffic. But the new H Street line runs over to the side, directly abutting the corridor's limited street parking. This significantly increases the chances of collision between the utterly inflexible streetcars and any poorly parked automobiles. There were a handful of minor accidents before the new system even opened for service.

"The golden age of streetcars, if you will—from the late 18th to the early 19th centuries—was when people depended on them to be the vital mass transit system for the city, because they didn't have other options," DeFerrari says. "The modern one only has a limited rationale. So my personal feeling is that it will remain a limited part of transit in D.C."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "D.C.'s Streetcar Nightmare."

Show Comments (2)