Can Blockchain Technology Reduce Third-World Poverty?

A better way to keep track of who owns what land.

In The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (2000), Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto argued that the underlying cause of Third-World poverty is weak property rights. Citizens of poor countries can't securely develop plots of land or put them up as collateral because they don't have clear legal titles. In a world "where ownership of most assets is difficult to trace and validate and is governed by no legally recognizable set of rules," de Soto wrote, "most assets, in short, are dead capital."

De Soto is now part of a new initiative to use the "blockchain," the technology that undergirds the digital currency Bitcoin, to solve the dead capital problem.

The San Francisco-based Bitcoin company BitFury announced last week that it was working with de Soto and the Republic of Georgia on a project to use blockchain technology to build a new land registry, as Forbes first reported. "By building a blockchain-based property registry," one Georgian government official said in a statement, the country "can lead the world in changing the way land titling is done and pave the way to additional prosperity for all."

A "blockchain" is essentially an online database with attributes that make it well-suited to protecting the integrity of land registries. The first thing that sets blockchains apart from other databases is that anyone with a computer and an internet connection can download a complete copy. And the information contained in the file is constantly updated through the internet (roughly every 10 minutes in the case of the Bitcoin blockchain). This means the most up-to-date information is always publicly accessible. And the government has no power to tamper with or delete the information stored on a blockchain because the data can only be altered by using secret passwords dispersed among users.

Yet uploading actual land titles to a blockchain is impractical because these distributed databases aren't designed to hold very much information. So companies in this space are devising elegant ways to anchor large data sets to the blockchain in ways that piggyback on its security and immutability, even when the specific information itself is stored elsewhere.

BitFury isn't the first company to work in this space. The Austin, Texas-based company technology company Factom has been in talks since 2015 with the government of Honduras to use blockchain technology to build a secure land registry in that country.

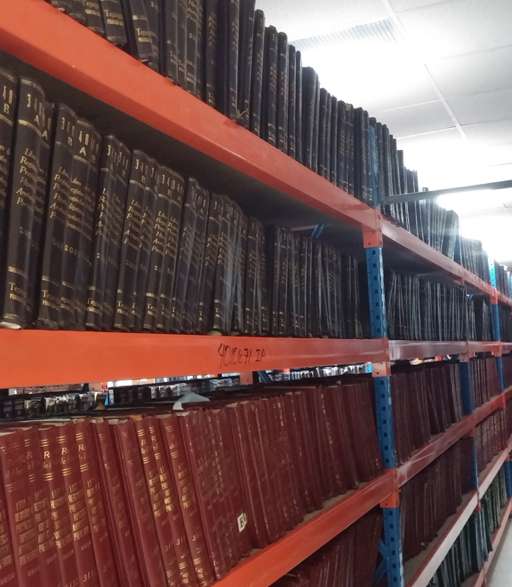

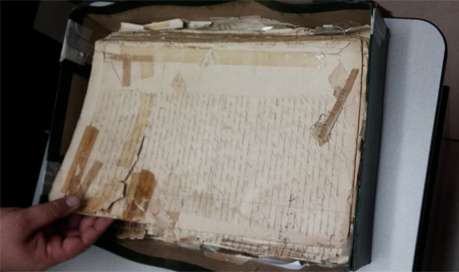

Currently, Honduras stores its title records in a room at the bottom of "dusty stairs" in a "nasty old government building," Factom CEO Peter Kirby said in an interview last year with Reason. Until recently, the room had no door.

"Anybody could go in, pull down a book, open up the spine, and replace a title record with a new title record," Kirby said. Some government bureaucrats have altered the records to assign themselves beachfront property. The Honduran government did at one point attempt to digitize its land records, but the database it built was unuseable.

A tamper-proof land-titling system, says Kirby, will lead poor countries to build "all of the infrastructure we take for granted in the developed world."

For more on blockchain technology, click below to watch a recent Reason TV video on Ethereum, a new blockchain platform that's well-suited for land registries and many many other types of applications:

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

LOL no. This will only make the problem worse. No one there can understand it and the government will just use it to justify greater corruption and theft. The key to reducing third world poverty is establishing property rights, true, but on the basis of even more fundamental rights - freedom of speech and religion. It really is as simple as that. If you think that technology will solve the problem of keeping public records in a 'nasty old basement' then I have a bridge to sell you. Or, "I'm from the high tech sector and I'm here to help."

"And the government has no power to tamper with or delete the information stored on a blockchain because the data can only be altered by using secret passwords dispersed among users."

Pretty sure that qualifies as an assertion that needs some evidence. How many people have to know a "secret" before it's no longer a "secret"?

You don't understand Blockchain.

What he said.

Under this scheme, only the property owner would have the password (key) to transfer the title. Nobody else could do it.

Potential problem: if you lose your key, your title is gone. Unrecoverable. Ooops. Now the title is yours in perpetuity.

So you'd need escrow agents - like bitcoin banks of a sort. So they'd have to have the keys so they could lock them away for you. So you'd need a trusted agent. Probably not the government in this case.

And at least every transfer would be a matter of public record.

You can color me skeptical of this solution for a couple of reasons.

1) Identifying the owners is only part of the problem. A bigger part may be getting all of the owners to agree to a sale.

Ejido land in Mexico is a good example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ejido

As part of land reform after the Mexican Revolution, they distributed Hacienda land to the people who worked it. I don't believe it was legal to sell this land immediately; a provision to do so was included in NAFTA in 1994. Meanwhile, all the descendants of the original owner have equally legitimate claims to the land.

So, between 1917 and 2017, If you have five generations of people with an average of three children each, then you have to get the notarized signatures of some 243 people to get clear title. Yeah, if you miss getting the signature of any one of them, he or she can legally take possession of the land back--after you've developed it. But identifying all the owners may not be the biggest challenge. The biggest challenge may be getting 243 family member to all agree to the same thing.

2) Complicated ownership structures that evolved from tribal custom aren't necessarily worse. The cloudy ownership issues, in fact, are sometimes the result of government trying to simplify ownership.

We know from Adam Smith that the customs, rules, morals, etc. that develop over time are both more complicated and closer to what they should be than when the government tries to impose simplistic laws from on high. As demonstrated by the distribution of Ejido land in Mexico, it wasn't the old systems of tribal land ownership that made that land unusable in the 21st century. The real problems started with land redistribution of Ejido land in the 20th century. And if the local customs and rules that evolved under tribal systems evolved the way they did for good reasons, then any solution that works well is likely to emulate the local customs and rules that prevailed under the tribal system.

I'd make two suggestions:

1) pater/mater familias

Make the family members choose one person to make decisions about the land's sales and usage, and give the other family members hold non-voting shares. This is respectful of both Spanish culture and emulates the way land was assigned by local chiefs in tribal society. It also gives them the flexibility and ownership clarity of a modern REIT.

2) In cases where the land is actually being used by someone--and has been used for some specific period of time--let the title be conferred on that person, and whatever arrangements have been made for compensation to other family members remain in place. This also emulates the way land was assigned in tribal societies--the land was yours as long as you were using it. When you stopped, the chief assigned it to someone else.

If the last time anyone on your side of the family used the land or exercised claim to it was three generations ago, why should your claim have the same weight as other family members who have continually used it for three generations?

What constitutes "using it"? Living on it? Farming it? How about renting it out for profit? How about just holding it and using it to secure debt? How about just holding it as a store of wealth to avoid monetary inflation?

All of that stuff would make for excellent use as far as I'm concerned.

One of the biggest problems we're talking about with Ejido land (and the subject of the article) is that so much of this kind of land (around the world) can't be used for anything specifically because there are so many people who would have to sign off on using it--even using it for collateral, etc.--that it isn't being used for anything. Why would a bank accept land as collateral when they 243 independent signatures, many of whom may hate each other? The bank can't take possession in case of default if they miss the signature of anyone who has a legal claim to it.

So, there's the case of land that isn't being used for anything at all--and there is a lot of that. On the other hand, there are other cases in which one part of a family four generations ago started farming it, and no one has made any other claims on it since the Revolution. I'm simply saying that those people shouldn't be thrown off the land by distant family members who haven't made any claim on the land in generations.

Suddenly telling people whose great-grandparents moved to Mexico city decades ago that they suddenly have a claim on land they didn't even know about isn't likely to unmuddy the ownership of all that unusable land. In other words, the first part of my solution wasn't meant to make things worse for people who've actually used the land--for whatever purpose. The first part of my solution was meant to make land usable that hasn't been usable in the past because there isn't any single person who can make definitive decisions, sign official documents, etc.

I quit myy office job and now I am getting paid 70 Dollars hourly. How? I work-over internet! My old work was making me miserable, so I was to try-something different. 1 years after...I can say my life is changed completely for the better! Check it out what i do...PO2....

========== http://www.E-Cash10.com

But will I be free to Gambol?

"This means the most up-to-date information is always publicly accessible. And the government has no power to tamper with or delete the information stored on a blockchain because the data can only be altered by using secret passwords dispersed among users."

What happens when people forget their passwords? What happens when someone gets hit by a bus and no one else knows their password? And what happens if hackers steal someone's password? All these things happen with bitcoin, with the result that some bitcoins are unusable and some are stolen, but how would this work with land?

"In The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (2000), Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto argued that the underlying cause of Third-World poverty is weak property rights. Citizens of poor countries can't securely develop plots of land or put them up as collateral because they don't have clear legal titles. In a world "where ownership of most assets is difficult to trace and validate and is governed by no legally recognizable set of rules," de Soto wrote, "most assets, in short, are dead capital.""

What about China, which also has weak property rights?

And has had a difficult time because of it. Most of the successful entrepreneurs are so because they're in bed with the people who can, with a wave of a hand, 'smooth over' title disputes.

Hell, Trump has built an empire specifically with the help of those people.

Chinese bureaucrats?

The only thing that will reduce third world poverty is to reduce third world mentality.

WTF does that even mean? Did Copperthwaite 'reduce third world mentality' when he presided over Hong Kong's rise? Did Kwai do that in Singapore? Don't think so.

Culture only matters if institutions don't do their jobs. Don't let culture matter.

bumpersticker($this);