Can Blockchain Technology Reduce Third-World Poverty?

A better way to keep track of who owns what land.

In The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (2000), Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto argued that the underlying cause of Third-World poverty is weak property rights. Citizens of poor countries can't securely develop plots of land or put them up as collateral because they don't have clear legal titles. In a world "where ownership of most assets is difficult to trace and validate and is governed by no legally recognizable set of rules," de Soto wrote, "most assets, in short, are dead capital."

De Soto is now part of a new initiative to use the "blockchain," the technology that undergirds the digital currency Bitcoin, to solve the dead capital problem.

The San Francisco-based Bitcoin company BitFury announced last week that it was working with de Soto and the Republic of Georgia on a project to use blockchain technology to build a new land registry, as Forbes first reported. "By building a blockchain-based property registry," one Georgian government official said in a statement, the country "can lead the world in changing the way land titling is done and pave the way to additional prosperity for all."

A "blockchain" is essentially an online database with attributes that make it well-suited to protecting the integrity of land registries. The first thing that sets blockchains apart from other databases is that anyone with a computer and an internet connection can download a complete copy. And the information contained in the file is constantly updated through the internet (roughly every 10 minutes in the case of the Bitcoin blockchain). This means the most up-to-date information is always publicly accessible. And the government has no power to tamper with or delete the information stored on a blockchain because the data can only be altered by using secret passwords dispersed among users.

Yet uploading actual land titles to a blockchain is impractical because these distributed databases aren't designed to hold very much information. So companies in this space are devising elegant ways to anchor large data sets to the blockchain in ways that piggyback on its security and immutability, even when the specific information itself is stored elsewhere.

BitFury isn't the first company to work in this space. The Austin, Texas-based company technology company Factom has been in talks since 2015 with the government of Honduras to use blockchain technology to build a secure land registry in that country.

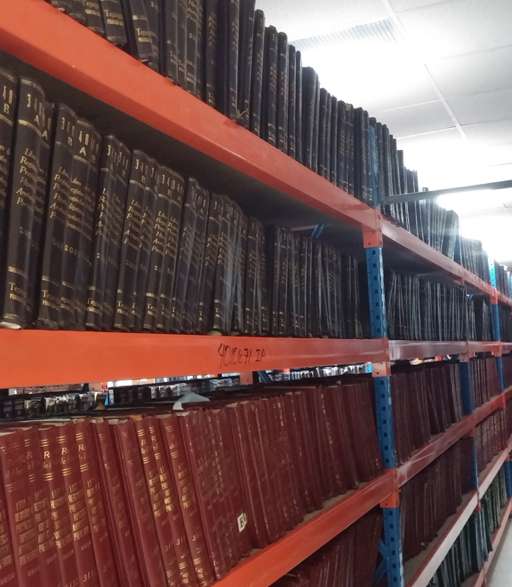

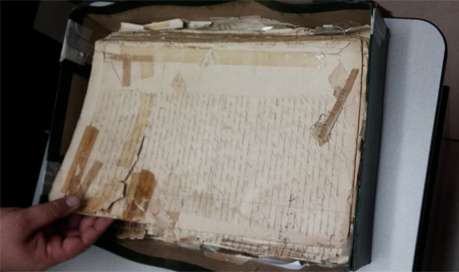

Currently, Honduras stores its title records in a room at the bottom of "dusty stairs" in a "nasty old government building," Factom CEO Peter Kirby said in an interview last year with Reason. Until recently, the room had no door.

"Anybody could go in, pull down a book, open up the spine, and replace a title record with a new title record," Kirby said. Some government bureaucrats have altered the records to assign themselves beachfront property. The Honduran government did at one point attempt to digitize its land records, but the database it built was unuseable.

A tamper-proof land-titling system, says Kirby, will lead poor countries to build "all of the infrastructure we take for granted in the developed world."

For more on blockchain technology, click below to watch a recent Reason TV video on Ethereum, a new blockchain platform that's well-suited for land registries and many many other types of applications:

Show Comments (19)