Does Joe Biden Actually Believe His Own Campus Rape Scare Statistics?

The federal government has blurred the lines between harassment, unwanted touching, and rape.

The activist coalition to reduce campus sexual assault—which includes celebrities, members of Congress, and even the Obama White House—has always expected the public to endorse a weird contradiction: college rape is a pervasive epidemic that touches a quarter or more of all female students, they say, but at the same time, it isn't serious enough to merit the application of stronger corrective measures.

By "stronger corrective measures," I mean the outright abolition of dormitories, or reinstatement of single-sex facilities, or other things along those lines.

If that sounds crazy, consider what society would demand of a factory that allowed more than 20 percent of its workers to be maimed, or an automobile manufacturer that installed faulty breaks in a quarter of its vehicles. We needn't even extend the analogy this far: if a hospital allowed a significant number of its patients to be raped, would there not be calls to shut down the hospital?

To be clear: I don't favor closing colleges, but only because I don't buy the activists' claim that campus sexual assault is an epidemic. The question, then, is why do activists support marginal solutions—affirmative consent, bystander intervention, one-sided sexual misconduct hearings—to a problem they consistently describe as a pervasive culture of violent crime?

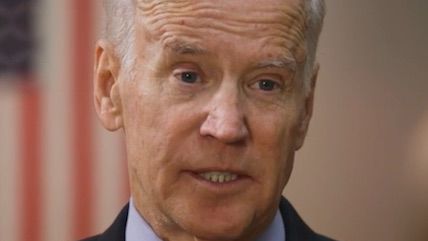

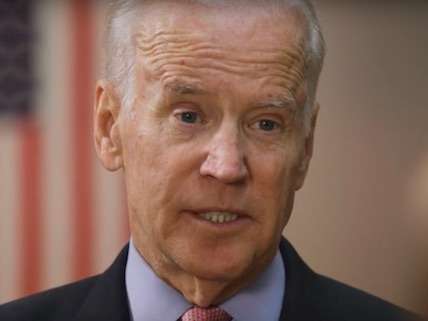

Vice President Joe Biden's recent interview with Mic's Antonia Hylton is a perfect illustration of this contradiction. In the interview, Biden defended the work he has done to reduce campus sexual assault, including championing the "It's On Us" bystander intervention campaign, and the Education Department's push to punish rape under the Title IX anti-harassment statute. But he also accepted the validity of scare statistics that, if accurate, would suggest the need for more direct intervention:

Mic: Well, but let's take Harvard for example, where I went to school. Forty seven percent of the women in my graduating class who interacted with single-sex social organizations reported, by the time that they graduated, they had been sexually assaulted. Do you think that that indicates a specific and localized crisis?

JB: Well, I think it indicates that there's a real problem at Harvard, and it's the responsibility of the president of Harvard University and the administration to go in and investigate it and if it's occurring and they can show that, get rid of the — get rid of those fraternities on campus that are engaged in it.

But "getting rid of those fraternities" wouldn't be nearly enough. The same survey that Hylton is citing put the overall, not-just-limited-to-fraternities number at 31 percent, and determined that the overwhelmingly most common place for women to be assaulted was campus dormitories.

Note that I'm using the word "assaulted" here because that's how Hylton phrased the statistic. But the actual survey did not find that 47 percent of some women and 31 percent of all graduating Harvard women had been sexually assaulted. Rather, it found that these women had been victims of "nonconsensual sexual contact." This seems like a meaningful difference, since "nonconsensual sexual contact" strikes me as a much broader category of behavior. Imagine, for instance, a male student brushing up against a female student at a party, or attempting to grind on her without asking first (keep in mind that under an affirmative consent standard, all contact is nonconsensual without specific prior agreement). The female student might describe this act as nonconsensual sexual contact—and she would be justified in doing so—even though her experience doesn't really rise to the level of sexual assault.

Nonconsensual touching is a problem, too. But an epidemic of teenagers not keeping their hands to themselves is not remotely the same thing as an epidemic of rape.

Unfortunately, this blurring of the lines that distinguish problematic behavior on campuses from criminal assault might become the most lasting legacy of the Biden-era anti-rape coalition. Thanks to federal guidance as relentlessly confusing as it is illiberal, universities are now policing harassment, nonconsensual touching, and forcible rape as if these behaviors are equally prevalent and similarly concerning. But the Title IX approach is simply ill-matched for the least and most serious of these offenses: rape should be handled by the police, and allegations of subjective harassment ought not to be policed at all.

Ironically, the problematic conduct falling in the middle—objective harassment, nonconsensual touching—might actually be best handled by the sorts of strategies some activists recommend: awareness campaigns, education about consent norms, alcohol abuse counselling, etc. But exaggerating the extent of the crisis—asserting that one in four women are victims, not just of unpleasant behavior, but of sexual assault—has made it much more difficult to meaningfully address it.

[Related: Five Years After the Feds Escalated the Title IX Inquisition, Are Students Ready to Sue?]

Show Comments (114)