Bad Fiscal Policies Are a Worse Scandal Than the Panama Papers

Trying to lessen your own tax burden isn't illegal, and shouldn't be.

If you haven't heard yet, the release of the so-called Panama Papers has revealed that top global leaders such as Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iceland's prime minister may be using companies and other business entities created by a Panama-based firm as a way to avoid taxes or conceal wealth. It's creating quite an uproar. Unsurprisingly, with very little evidence of actual illegality on the part of the law firm from which the documents were stolen—or most of its clients—the usual suspects are already calling for sanctions or dramatic and punitive changes to international tax laws.

The French finance minister, for instance, already put Panama back on the list of countries that aren't sufficiently willing to help enforce onerous French tax law. That's despite France's removal of Panama from its list of uncooperative states and territories in 2012 after reaching a bilateral agreement on precisely that issue.

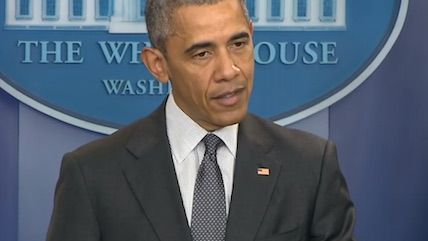

President Barack Obama, on the other hand, recognizes that most of the activities reported in the stolen pages are legal. As such, he wants to do something that might be even more radical than what France has done. He proposes making it illegal to legally reduce one's tax burden. Falling back on some generic and zero-sum concept of tax fairness, he told reporters that we "shouldn't make it legal to engage in transactions just to avoid taxes" and that he wants to enforce "the basic principle of making sure everyone pays their fair share."

No matter what paper you read or what program you listen to, this story is couched only in terms of a groundbreaking discovery that exposes how everyone and every company linked to an offshore account has run afoul of the legal system. Not true.

It is just a guess right now, but I predict that we will find out that most people who use tax havens are honest and law-abiding citizens—perhaps more so than politicians. As the Cato Institute's Dan Mitchell pointed out as soon as the papers came out, most parts of this story and other tax haven stories are non-stories.

International businesses, investors and entrepreneurs require international and neutral tax structures, such as the ones offered by Panama and Switzerland. The notion that having a company or a trust in Panama is automatically bad—or that because a few people use Panama accounts to do illegal things, all such arrangements are automatically bad—is ridiculous. Mitchell compares it to saying that "we shouldn't allow cars to be sold because someone may use one as a getaway car in a bank robbery."

Now, if someone is illegally hiding taxes from his government, he should be punished—in the same way the guy driving the getaway car should be—but we shouldn't punish the tax structures or the car company. If you want more global trade and more global investments, international bureaucracies such as the Organisation for Co-operation and Economic Development and governments around the world shouldn't make it harder to operate international businesses and engage in cross-border investment and business.

Unfortunately, that's the direction in which this whole drama is going. For years, France has punished its entrepreneurs and businesses with high taxes and terrible laws. As a result, last year alone, some 10,000 French millionaires called it quits and moved abroad. However, rather than reform its tax laws and streamline its government, it wants to put its grabby hands on some cash stored legally in Panamanian trusts. Why not, as long as the OECD is willing to help?

But it won't work in the long run. France and other high-tax nations can try very hard to destroy tax competition, financial privacy and the sovereignty of countries with better tax structures, but they still won't be able to afford their big and broken welfare states. Some European welfare states—e.g., Italy, Spain, and Greece—have already hit the wall, and it's only a matter of time until France joins their ranks.

Instead of going after countries such as Panama and the important and legal structures they offer to international businesses and investors, high-tax nations and the media should wait to see whether any laws were actually broken. And while they're waiting, they should reform their own governments' self-destructive fiscal systems. That's the real financial scandal.

COPYRIGHT 2016 CREATORS.COM

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The reason I'm hoarding gold bars and bitcoins in my converted ICBM silo is because if we keep running deficits in the same manner that we are doing now we are going to go broke. This is indicated by the recent increase in the inflation rate to 1,200% and Peter Schiff's increasingly prolific pronouncements of economic doom everywhere I roam on the Internet.

Get this through your head, slimy leftist. There's no way we can keep spending the way we do. The 432 billion dollar deficit for 2015 represents a 2,000 fold increase over that which was run up during the halcyon days of GWB and just shows how Obama is a failure at everything. The only way to pay down this deficit is to revoke the ponzie scheme of Social Security and Medicare and throw great-grandma out on the street. Time to get off the dole, 95-year old bitch.

And don't even think about asking tax cheats and criminals to pay a fraction of the estimated 1.2 trillion dollars *annually* that they skip out on. Fuck that. That's for you and I to pay. If we began to ask rich people to actually pay their fair share of taxes by-- the horruh-- passing actual laws that inconvenience some plutocrat why they'd probably go all Galt, march up a hill somewhere and throw a tantrum. Gee, we wouldn't want that. Better for you and I to pay those taxes.

To sort of agree with the this bit of American Socialist's faux screed, tax avoidance is a real problem when the peasants pay and the elite do not.

We are tax cattle, and they are the ranchers.

Yeah, but the best way to prevent such an outcome is to create a simplified tax code. Unfortunately, doing so will cause mouth breathers like AmSoc to bitch even harder.

"OH NOES! MUH TAX CREDITS!"

This 100%. And this article is the typical Reason bullshit that does nothing but make excuses for cronyist distortions.

most people who use tax havens are honest and law-abiding citizens...if someone is illegally hiding taxes from his government, he should be punished?in the same way the guy driving the getaway car should be?but we shouldn't punish the tax structures or the car company.

100% of useless tax gimmicks here in the US were put in place due to pressure by precisely the people who use those gimmicks. They don't have to break the law - because they OWN the law. And rather than spend even one nanosecond figuring out which tax laws and tax structures have been distorted/corrupted (so they can be fixed/simplified), this author excuses it all by pretending that only 'law breaking' is the problem. As if govt laws are written by aliens and there's nothing that anyone who supports a 'free market' can do about that.

And no doubt her next article will be crawling back on her hobbyhorse about ExImBank - as if that is even remotely as cronyist as most other distortions.

Towelie, you're the worst sockpuppet ever.

Feeling guilty about not taking care of your grandma again?

He doesn't feel guilty. It's Leviathan's job to take care of old people!

This is precisely the position of Comrade Bernie Sanders. From a 1981 New York Times story, revealing Bernie Sanders as the full totalitarian he is underneath his "democratic" socialism:

fuck you cut spending

I LUV YOU AMSOC YU AR SOO SMART!!!!

I love you too. Can you tell me how much your weekly check is from the federal government? A round number is ok.

Derp has a job and a mortgage. Not that you'd understand what that's like.

Also: seeing you get continuously shit on in the comments section is perhaps the most enjoyable experience one can have on the interwebs. Thank you for bringing your bullshit (and all the hilarity that always ensues) into our collective online lives.

🙂

you think bitcoins are more stable than USD? at this point maybe they are, but I remember the price jumping from under a hundred to over a thousand and then back almost instantaneously (well, within a few weeks, and that was a few years ago, to be fair)

He's mocking paranoid libertarians and conservatives, which he thinks are the same thing.

He's not very bright.

Do right-wing libertarians know the difference between the Soviet Union in the 1930s and Western Europe in the 21st century? Probably not from what I've read. They're not very bright.

"Pay no attention to the fact that I'm an admitted Stalinist - I'm only advocating for the type of squishy social democracy that's bankrupting Europe, not the scary kind that resulted in the starvation of millions!"

Really, you've proven time and again that you're not worth anyone's time. Please go find a new place to be proudly ignorant.

Woosh.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQB4nAjZIdE

Re: American Stultified,

How sweet! He disparages people who cheat the government.

Oh, shnookums!

Maybe throw YOUR great-grandma out on the street. She's certainly not my great-grandma.

C-

Hasn't your hero and most venerated messiah figure Block Insane Yomomma already accumulated enough debt and caused to America for your liking, you miserable little twerp? What the fuck would it take to make your sorry, worthless ass happy?

But if he is a Plutocrat and has the means to slide between jurisdictions so that he pays nothing in taxes, while the peasants pay and pay and pay, that seems to be fine and dandy with Reason. All of a sudden it's all about what is *legal*, instead of what is *just*.

I believe their point is that there is nothing just about the American tax system. It is 76,000 pages of gobbledy-gook that is designed to be inscrutable. The advantage that the wealthy have is due to the insanity of the tax system. However, they are not responsible for the existence of that system, Congress is.

It's the same as with the bailouts, TARP, rent seeking in general, etc. - don't blame the piggies for shoving to feed, blame the farmer who fills the trough.

Fucking incentives, how do they work?

(Hint: don't ask american socialist.)

Incentives are just like magnets, if that helps you understand any better.

You know, i bet american socialist is a juggalo. He's certainly got the intelligence for it.

I think that's how i'll picture him from now on.

He's a Big Money Rustla?

What did juggalos do to deserve such an insult?

Antijuggalism is the last respectable prejudice.

+ negative infinity insane clown posses [is that really the plural of "posse"?]

However, they are not responsible for the existence of that system, Congress is.

Indeed. All these so-called "loopholes" are written and signed into law by *individual human beings* that should not be re-elected until they quit fucking it up.

what's the over/under on how many iq points you lose the moment you get elected to congress?

Taxation of any kind is unjust; it's nothing more than institutionalized extortion. You can apply tax rules to everyone evenly, but all you're doing is creating a system that is fair, not just. Stealing everyone's TV on your block is fair, but not just, for instance.

Also, you might consider why those "plutocrats" are so motivated to risk asset seizure and possible prison time in order to avoid paying taxes. Maybe it has something to do with the tax rate?

he told reporters that we "shouldn't make it legal to engage in transactions just to avoid taxes"

This is already prohibited. It's called, among other things, the economic substance doctrine and allows the IRS to disregard transactions that have no justification outside of their tax consequences.

And it is a notoriously gray area of tax law. As such, lawyers can be deployed to argue over it.

Yeah, that's what I do for a living.

And since members of Congress are 68 times more likely to have practiced law than the citizens they represent, I'd say they're doing exactly what they need to do to protect their own.

Just one question,what is the 'fair share' of taxes? I see it a lot ,but,there's never a number given.

Fair share, to them, is whatever the thieves and parasites say it is. But what it actually means is "how much we can steal from you before you actually revolt".

It's simple: are they still rich? Then it's not fair.

Oh, that's easy.

$15 an hour.

That's not good enough for the higher ups in the NYPD it seems.

In the 1972 election, George McGovern's promise to give every US citizen $1000 wasn't quite radical for Bernie Sanders. Comrade Bernie instead supported Benjamin Spock on the Peoples Party ticket, which argued that the state must guarantee not only a minimum wage but also a maximum wage.

In subsequent elections, Comrade Bernie naturally rejected reactionaries like Carter and Mondale. Instead, he supported the Trotskyite Socialist Workers Party and even served as an elector for the party in the unlikely event that it would be selected by Vermont voters.

Hillary is right when she questions whether Comrade Bernie is a Democrat. It's one of the few truthful implications that she has ever made.

Being rich, by definition, means not having paid a fair share.

Rich is relative. To me, Trump is rich. To some field laborer, I am rich. To some Ethiopian, the field worker is rich.

How far down the rabbit hole do these clowns want to go?

Have money in your bank account?

If yes, then more.

It's quite simple really. Are your "rich" even after paying your taxes? If you answered yes, then you haven't paid your "fair share" yet.

If you are not a registered Democrat and vocal supporter of Progressivism, it's whatever you make after about $50k.

---Just one question,what is the 'fair share' of taxes? I see it a lot ,but,there's never a number given.---

How much is fair?

How much you got?

Now, if someone is illegally hiding taxes from his government, he should be punished.

I'm gonna have to disagree.

All taxation is theft. Tax avoidance and tax evasion are self-defense. Self-defense should not be punished. Granted, it might/will be punished but that doesn't mean that it should be punished.

"...to avoid taxes or conceal wealth."

The first is a crime by definition, the second is only a crime in the few places that tax wealth. And the second is an extremely obvious goal that every stinking-rich person would want to do also, so I'd need an explanation in each case how the person outed has actually committed a crime.

[Obama said} we "shouldn't make it legal to engage in transactions just to avoid taxes".

"Oh, very well. I'm engaging also to have fun."

You're the *president*, Barack. You don't *have* to sign stuff.

Not so by the usual cadre of Marxians in Mexico, who are already alleging that the current president must have offshore money accounts and accusing companies of cheating the taxman, as if it were a patriotic duty to pay taxes. Oh, by the way: it's not.

"Patriotic duty" isn't an enforceable thing. You have a legal duty to pay the taxes you legally owe. It is not a crime to engage in lawful activities that reduce that number.

I don't know. Personally, I see it as my patriotic duty to deprive the parasite state of every single penny I can possibly get away with keeping from them.

(and a few that I couldn't get away with keeping from them if they knew about it)

/s

Trying to lessen your own tax burden isn't illegal, and shouldn't be.

Trying to keep your private business private shouldn't be illegal, but it is.

For the same reason that a slave owner needed to know all of productive activity of his chattel slaves, the state needs to know all of the productive activity of its subjects. For example, a slave may tend a private garden that produces a surplus or may receive wages from another for work performed outside of his duties to his owner. If these amounts are significant, the slave owner will naturally demand a portion of the surplus or the wages received. The slave would naturally have a strong incentive to deceive his owner as to magnitude of the surplus or the wages received. Tax evasion, money laundering, and undeclared foreign asset accounts -- all illegal -- are modern analogues to the problem that an enterprising slave would have.

If you view this from the point of view that essentially what Obama is talking about is massively simplifying the tax code, at least at face value, this isn't such a bad idea if they went ahead and did this across the board. In would be massively disruptive in the short term, but if everyone just paid their actual tax rate regardless of deductions etc. than perhaps people would finally realize how much their tax burden really is.

Of course, back here in reality this measure won't happen considering the very people deciding the legislation are apparently the same people using these tax havens. Big surprise, right?

Bear in mind that this is coming from a guy who believes that a private company relocating to another country in order to take advantage of more favorable tax laws is effectively committing treason and should be prevented from leaving. The government preventing the free movement of private property in order to retain corporate tax income and calling it a patriotic duty...I'm not sure that's quite Bolivarianism but I think that's getting pretty close. At what point do you just call it "nationalization" in deed if not word?

uptil I looked at the bank draft saying $8885 , I didn't believe that my mother in law woz like they say truly taking home money in there spare time at their laptop. . there great aunt haz done this less than 17 months and as of now repayed the mortgage on there home and bourt a great Renault 4 . see

Copy This Link inYour Browser

http://www.MaxPost30.com

Heck, the administration wouldn't even let Boeing (?) build a factory in a Right to Work state.

Aside from the reason why there are few Americans and American firms listed in the Panama Papers dump is that we operate similar secretive functions here. Notably Nevada:

"Nevada, for example, comes in at No. 8 on the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists' list of the top 10 most popular tax havens in the Panama Papers. And it's growing: In 2012, Nevada pulled in about $133 million from corporate filings, VegasInc reported. In 2002, it brought in merely $43 million in revenue, Reuters reported."

Most large corporations have other 'legal' means of reducing and avoiding US taxes, such as incorporating in another country, such as Ireland, or merging with a foreign company, even though the bulk of the sales and manufacturing are performed here. Not to mention the massive drop in taxes for the wealthy and corporations since the 60's. (Yeah, you'll hear how US taxes kill companies and they're sky high..But Google it. It's not true. )

But, really, what exactly is wrong with "the basic principle of making sure everyone pays their fair share."? Shouldn't we all be willing to support the nation that supports us in a fair fashion, or is it OK to be a tax avoider if you can find the loopholes that our sell-out Congress sticks in their bills? I'm with Obama on this one. Everyone should pay their share.

Define "fair share" in explicit terms.

Yea how did you determine fair share? And not sure there has been a massive drop in taxes for the wealthy and corporations since the 60s...please compare the effective rates.

Registering a corporation in a state really has nothing to do with taxation. I used to have a Nevada corporation, simply because California's incorporation process was so onerous and expensive. Nevada only cost me about $100 to form an LLC, and until Nevada got greedy and started forcing me to buy a Nevada business license, I stayed in Nevada. Then I moved to a cheaper state. When filing taxes, it made no difference that I used a Nevada LLC, I still owed the same taxes.

Excellent article that misses the central point: Federal taxes do not fund federal spending. A Monetarily Sovereign government (which the U.S.is and France is not) neither needs nor uses tax dollars.

Even if all federal taxes fell to $0, the U.S. government could continue spending, forever. The U.S. government creates its sovereign currency, ad hoc, by paying bills.

So all the whining about businesses, (which pay our salaries) not paying enough taxes is merely an appeal to the economic ignorance of the American public.

No, Social Security is not going broke. Nor is Medicare. Nor is the U.S. government, despite what John Boehner tells you. And no, the federal debt is not too high, nor is the federal deficit.

Federal taxes do not fund anything. Learn that, and the politicians or the media won't be able to fool you any longer

So what do they do with the taxes they collect? Why are they collecting them? Would you advocate no taxation?

The U.S. government collects taxes in part to keep up the charade that the American public needs to pay taxes to fund entitlements, defense, etc., which works as another political football for election season (e.g., the perennial debate over "fair share" and "fixing the tax code"). Additionally, foreign governments and investors would start to get nervous if the U.S. government relied entirely on monetary policy to fund itself. The dollar remains strong relative to other currencies, however, because of the widespread belief even among sophisticated international investors that the U.S. will continue to fund its debts. Basically, as long as investors prefer dollars over other currencies, the U.S. can spend indefinitely without needing to collect taxes.

This is what I've heard, but I can't say whether it's true. However, although CBO projects that spending will balloon amid chronic federal budget deficits, this hasn't dampened investors' appetite for U.S. debt. This fact lends credibility to the narrative above.

Tax dollars in the US do the same thing as tax dollars in France: they redirect resources from the private sector to government and rent seekers. That very much is "funding" of stuff with federal taxes.

Yes, the US could print as much money as it wanted to in order to formally meet its debt obligations. While that technically wouldn't mean "going bankrupt", it would amount to the same thing: money would be worthless, the US government couldn't borrow or spend anymore, retirees wouldn't get any money from Social Security. Germany experienced this kind of hyperinflation in the 1920s and 1930's and it was devastating.

In different words, you are a complete fool.

Even if all federal taxes fell to $0, the U.S. government could continue spending, forever. The U.S. government creates its sovereign currency, ad hoc, by paying bills.

Paying bills from whom with what?

Printing money simply amounts to a tax on people holding cash.

"He proposes making it illegal to legally reduce one's tax burden."

this is sort of like dangling cheese in front of a mouse, and then when they get too close, you crush their heads.

there is no magic, universally agreed upon number. fair share is defined by congress. so long as you pay the legally required amount, then you've paid your fair share, and everyone else can shut up already.

The reports of this scandal never seem to mention that the good ol' USA is the third largest tax haven in the world. Switzerland, Hong Kong, and the US are the three largest tax havens in the world, with Panama ranking only 13th. This is only a scandal to those who know nothing about financing and international taxation. That said, the US FATCA put me out of a job in France because my employer didn't want to go to the trouble of hiring me through a Swiss subsidiary to escape the US reporting requirements.

So people should be punished if they avoid the soda tax or if they avoid the gasoline tax or if they avoid the ACA penaltax?

If by punished, you mean "shot and dumped into a mass grave" then, yes!

/Amsoc

Want to earn from home by working basic work using your laptop for 2 to 4 h on daily basis, get paid 62 bucks fifty-eight minute ZA and get a paycheck every week and choose yourself your working time?Its original site...BNH005

http://www.payability70.com

I've made $76,000 so far this year working online and I'm a full time student.I'm using an online business opportunity I heard about and I've made such great money.It's really user friendly and I'm just so happy that I found out about it.

Open This LinkFor More InFormation..

??????? http://www.selfcash10.com

"President Barack Obama, on the other hand, recognizes that most of the activities reported in the stolen pages are legal. As such, he wants to do something that might be even more radical than what France has done. He proposes making it illegal to legally reduce one's tax burden. Falling back on some generic and zero-sum concept of tax fairness, he told reporters that we "shouldn't make it legal to engage in transactions just to avoid taxes" and that he wants to enforce "the basic principle of making sure everyone pays their fair share."

Is he really a true believer? I would love for the stupid motherfucker to do that. We would get a Zapruder-style video starring Obumbles inside of a week.

Go ahead Barry, give it a shot.

Someone remind me, how many Reason staff voted for this evil piece of shit?

Are you single tonight? A lot of beautiful girls waiting for you to http://goo.gl/X6JhyG

uptil I looked at the bank draft saying $8885 , I didn't believe that my mother in law woz like they say truly taking home money in there spare time at their laptop. . there great aunt haz done this less than 17 months and as of now repayed the mortgage on there home and bourt a great Renault 4 . see

Copy This Link inYour Browser

http://www.MaxPost30.com

Start making more money weekly. This is a valuable part time work for everyone. The best part work from comfort of your house and get paid from $100-$2k each week.Start today and have your first cash at the end of this week. For more details Check this link??

Clik This Link inYour Browser?

???? http://www.selfCash10.com

I am nine to five work by one hour 85 dollars....U My old work was bad for me ,so I was forced to try something new? Two Years have passed since And I say it was the wisest decision i ever made! Here at this what I do?

--- http://www.alpha-careers.com

Start making more money weekly. This is a valuable part time work for everyone. The best part work from comfort of your house and get paid from $100-$2k each week.Start today and have your first cash at the end of this week. For more details Check this link??

Clik This Link inYour Browser

? ? ? ? http://www.MaxPost30.com

til I saw the draft which was of $6881 , I didnt believe that my mother in law had been realy taking home money part-time on their laptop. . there best friend has done this 4 only twelve months and at present took care of the mortgage on there condo and got a top of the range Subaru Impreza . Learn More ....

Click This Link inYour Browser....

?????? http://www.Reportmax20.com

I've made $76,000 so far this year working online and I'm a full time student.I'm using an online business opportunity I heard about and I've made such great money.It's really user friendly and I'm just so happy that I found out about it.

Open This LinkFor More InFormation..

??????? http://www.selfcash10.com

before I saw the bank draft which had said $9426 , I didnt believe that...my... brother woz like actualy earning money part-time at there labtop. . there uncles cousin has done this 4 less than fifteen months and by now repaid the dept on there place and got a great new Mini Cooper . read the full info here ...

Clik This Link inYour Browser??

? ? ? ? http://www.SelfCash10.com

Start making more money weekly. This is a valuable part time work for everyone. The best part work from comfort of your house and get paid from $100-$2k each week.Start today and have your first cash at the end of this week. For more details Check this link??

Clik This Link inYour Browser?

???? http://www.selfCash10.com

Don't forget to bring a towel!

I was high last night, in any case.

Epi, don't come in here and try to act like you're ever NOT high. Much like the Libertarian Moment, you not being high is a purely speculative situation.

I was going to respond to your comment, X, but then I got high.

Do you have any Cheetos?

I might get some from the vending machine later.

Dave's not here, man.

'Cuz I'm the tax man

And you're working for no one but me

I was thinking Soylent Green is probably closer to his ideal society.