Does the 1st Amendment Apply to Political Ads in Public Transit Systems? SCOTUS Refuses to Weigh In, Clarence Thomas Dissents

Supreme Court declines to hear arguments in American Freedom Defense Initiative v. King County.

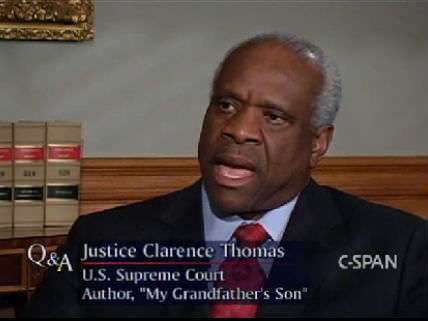

The U.S. Supreme Court today declined to take up a First Amendment case out of Seattle which asked whether the government may refuse to run certain political ads in a public transit system due to the political content of those ads. Writing in dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Samuel Alito, faulted his colleagues for refusing to take the case and thereby failing "to bring clarity to an important area of First Amendment law."

At issue in American Freedom Defense Initiative v. King County is the Seattle metropolitan area transit authority's decision to refuse to run an advertisement that featured the faces of 16 terrorists wanted by the federal government accompanied by their names and the message, "AFDI Wants You to Stop a Terrorist. The FBI Is Offering Up To $25 Million Reward If You Help Capture One Of These Jihadis." AFDI is a conservative nonprofit headed by Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer. According to county officials, the group's proposed message is "false or misleading" because the State Department, not the FBI, has offered the reward. The advertisement was also rejected on the grounds that it would be "demeaning and disparaging" to Muslims "by equating their dress and skin color with terrorists."

If the same message had been written on a placard and that placard had been displayed on a Seattle street or in a Seattle park, any government attempt to silence or restrict the message would be subjected to exacting judicial scrutiny under the First Amendment. That's because the Supreme Court has long recognized that the First Amendment stands as a bulwark when the government tries to restrict speech in a "traditional public forum," such as public streets or public parks.

The Supreme Court has taken a different approach, however, when it comes to other types of government property. In June 2015, for example, in Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans, the Court ruled that the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles did not violate the Constitution when it refused to create a specialty licensing plate bearing the image of the Confederate battle flag. License plates, the Court said, do not qualify as designated public forums.

What about public transit systems? In the present case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled in favor of the Seattle-area system and its rejection of the controversial "wanted poster" ad. As the 9th Circuit observed, the plaintiffs "contend that the advertising space on buses is a designated public forum. We disagree."

Yet several other federal circuits have reached the opposite conclusion. According to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, for example, once a public transit authority decides to accept "political advertising" it "has converted its subway stations into public fora." At that point, the D.C. Circuit argued, the First Amendment kicks in.

In other words, the First Amendment currently applies differently in some parts of the country versus others in the context of government restrictions on political advertisements in public transit systems. It was this circuit split that apparently captured the interest of Justice Clarence Thomas.

"Materially similar public transit advertising programs should not face such different First Amendment constraints based on geographical happenstance," Thomas wrote today. In Thomas' view, the Supreme Court had no business "shy[ing] away from this First Amendment case. It raises an important constitutional question on which there is an acknowledged and well-developed division among the Courts of Appeals. One of this Court"s most basic functions," Thomas declared, "is to resolve this kind of question."

Justice Thomas' dissent from denial of certiorari in American Freedom Defense Initiative v. King County is available here.

Show Comments (54)