The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

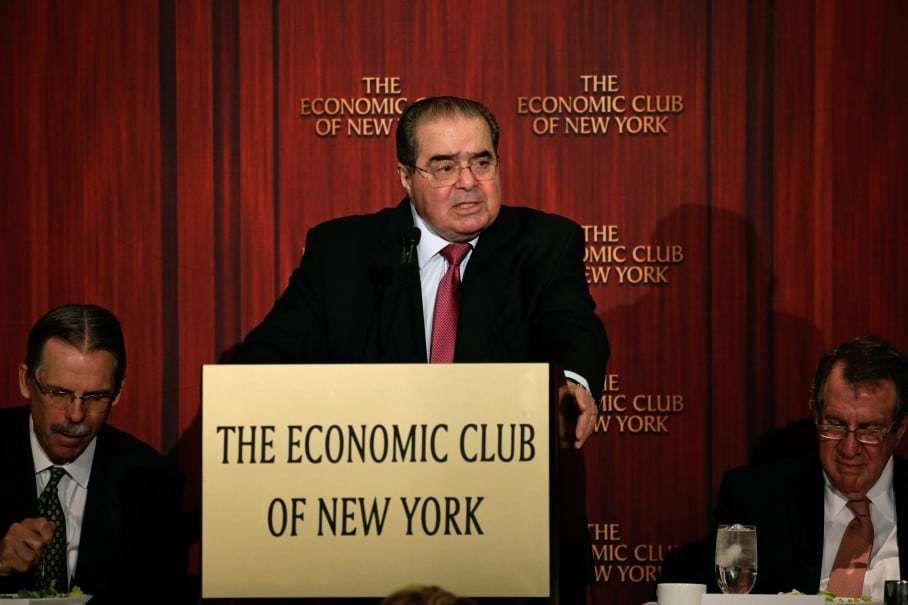

The passing of a legal giant -- Antonin Scalia, R.I.P.

Today the nation lost a legal giant. Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, the longest-serving member of the current Supreme Court, was found dead of natural causes at a West Texas resort. He was 79. He will be missed.

It is no exaggeration to say that Justice Scalia was the most consequential jurist of the past 35 years. A persistent, pugnacious and persuasive advocate for textualist statutory interpretation and originalist constitutional interpretation, he had an outsize effect on his colleagues, the court and the course of the law. More than anyone else, Justice Scalia is responsible for the renaissance of these interpretive methodologies and the displacement of "living constitutionalism" and reliance upon legislative history.

Before Justice Scalia joined the court, justices had no reluctance to join an opinion suggesting that statutory text could illuminate congressional intent where the legislative history was inconclusive. The issuance of such an opinion today, by any justice, is inconceivable. During the Warren and Burger courts, constitutional opinions often gave little consideration to the original meaning of the relevant text. Today, however, justices often duel over original meaning (see, e.g., the competing opinions in D.C. v. Heller). This, too, is largely due to Justice Scalia,

Though known as an arch-conservative, Justice Scalia did not hew a political line in his decisions. As criminal defense attorney Scott Greenfield noted, Justice Scalia could be the worst justice for criminal defendants, but he could also be the best. Justice Scalia would not invent or discover unwritten rights in the constitution, but he would vote to strictly enforce those that are enumerated, such as the requirement that defendants may confront the witnesses against them or the defendant's right to a jury trial.

Agree with him or not, Justice Scalia's opinions were almost always worth reading, not only for their reasoning but for their wit. His dissents, in particular, could be quite a ride. (His opinion in PGA Tour v. Martin is one of my favorites, and not just for the Vonnegut reference.) Indeed, there is a book: Scalia Dissents.

Justice Scalia put sincere effort into his opinions. It is often said Justice Scalia knew his audience extended well beyond his colleagues or even the lower courts. He often wrote for the public, and law students in particular. He sought to have an influence on legal minds - and he did.

Justice Scalia was hardly infallible. There will be plenty of time to consider the substance of his legacy, and the extent to which he remained true to his own stated jurisprudential ideals. Today, however, we should remember a man who had a deep influence on all of us who work with the law, remember his family and remember his friends - who included some of the most liberal members of the court - and remember the great life he led.

Show Comments (0)