The Fiction That Drug Trafficking Is 'Inherently Violent' Could Harm Sentencing Reform

Watered down improvements to federal mandatory minimums may get watered down further.

Abusing the word "violent": It's not just for outraged college students trying to fabricate harms in order to shut down speech they don't like.

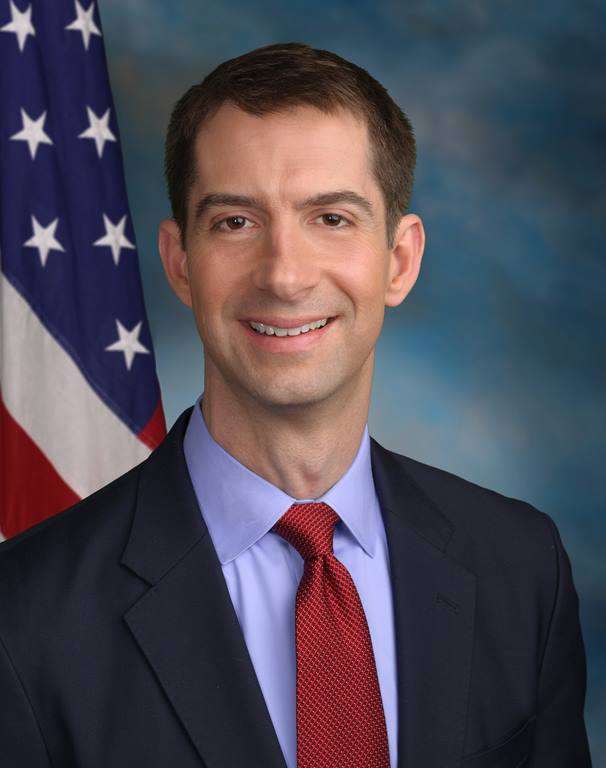

Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas is abusing the word "violent" to attack the bipartisan Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, which would reduce mandatory minimum sentences (in some cases retroactively) for a host of drug-related crimes. Cotton is claiming the bill will, as it stands, would "lead to the release of thousands of violent felons." His claim is not really true, but his argument seems to have traction. As Brian Doherty noted yesterday, the legislation may see cuts in a couple of areas connected to whether a criminal had a weapon during a drug offense or after having three drug or violent crime arrests.

What makes Cotton's claim ring false? Cotton believes that drug trafficking is inherently a violent crime, and as the Washington Post notes, pretty much sees everybody potentially released by the legislation as violent criminals. Caroline Rabbitt, Cotton's spokesperson told the Post, "It is naive to think that dealing cocaine and taking part in its import and distribution is 'nonviolent.' That's a fantasy created by the bill's supporters and no serious federal law enforcement expert would agree with it."

Ah, but they do. In fact more than 130 "law enforcement experts" do. Republican Sens. Mike Lee (Utah) and Chuck Grassley (Iowa), who have hammered out this legislation, have distributed letters signed by dozens of current and former police chiefs, sheriffs, district attorneys and others supporting the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act. Lee and Grassley will be holding a briefing this afternoon to discuss the support of the law.

Cotton's suggestion that the reforms will result in dumping criminals out into the street is not to be treated seriously. The law does indeed reduce mandatory minimums retroactively, but it's not automatic. Prosecutors can resist and a judge would make the call based on the circumstances of each case. Molly Gill, government affairs counsel for Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) notes that the impact of the bill would actually be fairly small as it stands, given the number of people in federal prison.

"We're talking about 2,300 people over a period of several years, and not all those people would get reductions," Gill says, of those who would be affected by the parts of the act that may get dropped.

She also objects to the idea that all drug traffickers are "violent."

"I would say that I think his view is a minority a view," she says. "It's definitely not the view of 80 percent of the voters who think we should be eliminating mandatory minimums for drug offenders." It's also not an accurate analysis of who is serving federal time for drug crimes. According to a congressionally funded task force report (from the Charles Colson Task Force), almost half the people in prison for drug crimes have few if any prior convictions. A quarter have no criminal history at all. Fewer than 25 percent were sentenced for having or using a weapon for a crime.

As it stands, the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act is itself a compromise from the Smarter Sentencing Act Lee had proposed, Gill notes. The Smarter Sentencing Act would have reduced mandatory minimums and changed sentences for almost all drug cases, affecting tens of thousands of people a year. This act now being considered is much more limited, at Grassley's demand.

But if you think all drug crimes are "violent," would you get on board for any sentencing reforms at all? Dara Lind at Vox wonders if it's even possible to get Cotton to support any sort reduction in mandatory minimums given the language he's using:

If you believe that every drug dealer is violent, then you're not going to get on board with a bill reducing mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes. You're not going to get on board with a bill that allows some drug offenders currently in prison to take classes and get jobs in exchange for "good time" credits. In short, you're not going to support the Senate bill, because that's what the Senate bill does.

The fact that a judge would actually be in the position to decide whether or not an offender represents a threat apparently doesn't matter (because, Cotton complains, so many of the courts are filled with "liberal Obama judges").

I contacted Lee's office for a reaction, and he provided a prepared statement: "We're working to find a path forward that addresses some of the criticisms while at the same time maintaining both the core principles and significance of the bill and the broad bipartisan support that the bill has already garnered." Grassley and Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), the sentencing act's other sponsor, have put out statements that say the same.

Show Comments (28)